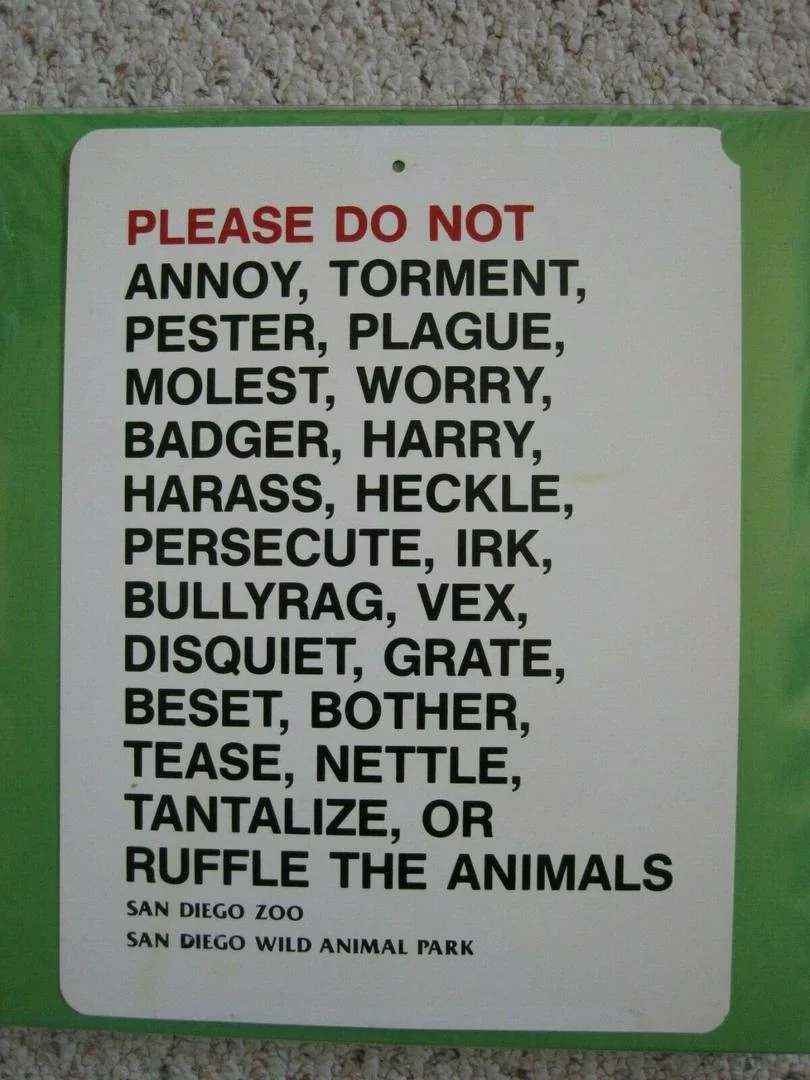

Some words become famous for their implausibly specific definitions:

ucalegon: a neighbor whose house is on fire

nosarian: one who argues that there is no limit to the possible largeness of a nose

undoctor: to make unlike a doctor

Mrs. Byrne’s Dictionary of Unusual, Obscure, and Preposterous Words, by Josefa Heifetz Byrne, collects examples ranging from atpatruus (“a great-grandfather’s grandfather’s brother”) to zumbooruk (“a small cannon fired from the back of a camel”). My own favorite is groak, “to watch people silently while they’re eating, hoping they will ask you to join them.”

Alas, most of these don’t appear in the magisterial Oxford English Dictionary. Accordingly, in 1981 Jeff Grant burrowed his way into the OED in a deliberate search for obscure words. When he reached the end of A he sent his 10 favorite finds to the British magazine Logophile:

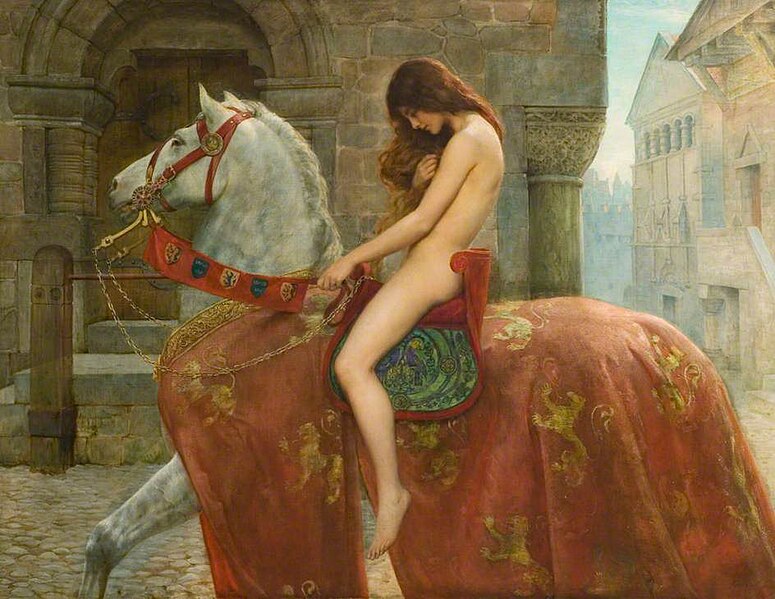

acersecomic: one whose hair was never cut

acroteriasm: the act of cutting off the extreme parts of the body, when putrefied, with a saw

alerion: an eagle without beak or feet

all-flower-water: cow’s urine, as a remedy

ambilevous: left-handed on both sides

amphisbaenous: walking equally in opposite directions

andabatarian: struggling while blindfolded

anemocracy: government by wind

artolatry: the worship of bread

autocoprophagous: eating one’s own dung

“I have been working slowly through ‘B’ and so far my favourite is definitely ‘bangstry’, defined as ‘masterful violence’, an obsolete term that is surely overdue for a comeback.”

(From Word Ways, November 1981.)