There was an old man who said, “Do

Tell me how I’m to add two and two!

I’m not very sure

That it does not make four,

But I fear that is almost too few.”

A mathematician confided

A Möbius strip is one-sided.

You’ll get quite a laugh

If you cut one in half,

For it stays in one piece when divided.

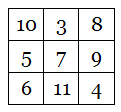

A mathematician named Ben

Could only count modulo ten.

He said, “When I go

Past my last little toe,

I have to start over again.”

By Harvey L. Carter:

‘Tis a favorite project of mine

A new value of π to assign.

I would fix it at 3,

For it’s simpler, you see,

Than 3.14159.

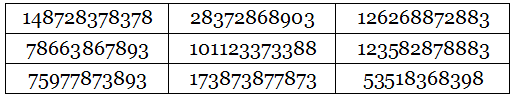

J.A. Lindon points out that 1264853971.2758463 is a limerick:

One thousand two hundred and sixty

four million eight hundred and fifty

three thousand nine hun-

dred and seventy one

point two seven five eight four six three.

From Dave Morice, in the November 2004 Word Ways:

A one and a one and a one

And a one and a one and a one

And a one and a one

And a one and a one

Equal ten. That’s how adding is done.

(From Through the Looking-Glass:)

‘And you do Addition?’ the White Queen asked. ‘What’s one and one and one and one and one and one and one and one and one and one?’

‘I don’t know,’ said Alice. ‘I lost count.’

‘She can’t do Addition,’ the Red Queen interrupted.

An anonymous classic:

![\displaystyle \int_{1}^{\sqrt[3]{3}}z^{2}dz \times \textup{cos} \frac{3\pi }{9} = \textup{ln} \sqrt[3]{e}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cdisplaystyle+%5Cint_%7B1%7D%5E%7B%5Csqrt%5B3%5D%7B3%7D%7Dz%5E%7B2%7Ddz+%5Ctimes+%5Ctextup%7Bcos%7D+%5Cfrac%7B3%5Cpi+%7D%7B9%7D+%3D+%5Ctextup%7Bln%7D+%5Csqrt%5B3%5D%7Be%7D+&bg=ffffff&fg=000&s=0&c=20201002)

The integral z-squared dz

From one to the cube root of three

Times the cosine

Of three pi over nine

Equals log of the cube root of e.

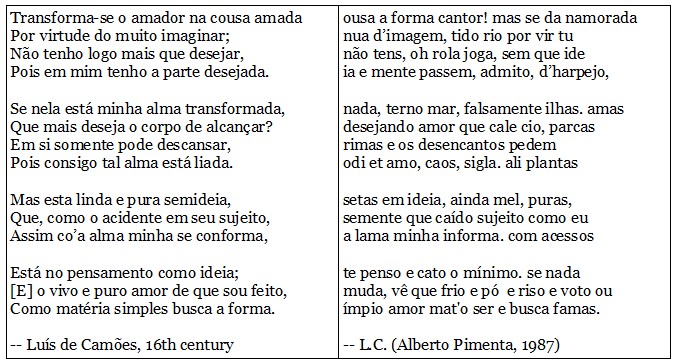

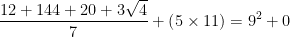

A classic by Leigh Mercer:

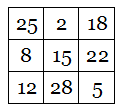

A dozen, a gross, and a score

Plus three times the square root of four

Divided by seven

Plus five times eleven

Is nine squared and not a bit more.

UPDATE: Reader Jochen Voss found this on a blackboard at Warwick University:

If M’s a complete metric space

(and non-empty), it’s always the case:

If f’s a contraction

Then, under its action,

Exactly one point stays in place.

And Trevor Hawkes sent this:

A mathematician called Klein

Thought the Möbius strip was divine.

He said if you glue

The edges of two

You get a nice bottle like mine.