In a French journal Oscar Wilde once saw the drawing of a bonnet.

Under it were the words “With this style the mouth is worn slightly open.”

In a French journal Oscar Wilde once saw the drawing of a bonnet.

Under it were the words “With this style the mouth is worn slightly open.”

“How happy many people would be if they cared about other people’s affairs as little as about their own.” — G.C. Lichtenberg

“Most people enjoy the inferiority of their best friends.” — Lord Chesterfield

“We all have strength enough to endure the misfortunes of others.” — La Rochefoucauld

“I set it down as a fact that if all men knew what each said of the other, there would not be four friends in the world.” — Pascal

That is a simple rule, and easy to remember. When I, a thoughtful and unblessed Presbyterian, examine the Koran, I know that beyond any question every Mohammedan is insane; not in all things, but in religious matters. When a thoughtful and unblessed Mohammedan examines the Westminster Catechism, he knows that beyond any question I am spiritually insane. I cannot prove to him that he is insane, because you never can prove anything to a lunatic — for that is a part of his insanity and the evidence of it. He cannot prove to me that I am insane, for my mind has the same defect that afflicts his. All Democrats are insane, but not one of them knows it; none but the Republicans and Mugwumps know it. All the Republicans are insane, but only the Democrats and Mugwumps can perceive it. The rule is perfect: in all matters of opinion our adversaries are insane.

— Mark Twain, Christian Science, 1907

When Joseph Addison lent a sum of money to his friend Temple Stanyan, Stanyan became meekly agreeable, unwilling to argue with Addison as he used to.

At last Addison told him, “Sir, either contradict me or pay me my money.”

Biographer Peter Smithers calls this “a salvo of which Johnson himself might have been proud.”

Andrew Carnegie’s rules for speaking:

As a boy he’d joined a debating club, and “I know of no better mode of benefiting a youth than joining such a club as this. … The self-possession I afterwards came to have before an audience may very safely be attributed to the experience of the ‘Webster Society.'”

(From his autobiography.)

“King James said to the fly, Have I three kingdoms, and thou must needs fly into my eye?” — John Selden

“The autocrat of Russia possesses more power than any other man in the earth, but he cannot stop a sneeze.” — Mark Twain

Why do people in bygone days wear such gloomy expressions? In the 16th and 17th centuries, smiling wasn’t encouraged in part because of poor dental hygiene. Louis XIV had no teeth, and the Mona Lisa may have been trying to hide gaps or stains in her smile.

Beyond the dental challenge, broad smiles and open laughter were often actively criticized, seen as reflecting a distressing lack of emotional control. Upper-class manners insisted that a boisterous laugh was a sign of poor breeding, really no better than a yawn or a fart. A French Catholic writer argued, in 1703, ‘God would not have given humans lips if He had wanted the teeth to be on open display.’ Children might smile, to be sure, but an adult should have learned to know better.

Fashionable audiences disdained laughing aloud — Molière said that this goal was not to entertain but to “correct the faults of men.” And in Protestant countries people sought to “walk humbly” in the sight of God — one writer commented that in his view, the Almighty “allowed of no joy or pleasure, but of a kind of melancholy demeanor or austerity.” This finally changed with the Enlightenment — John Byrom wrote in 1728, “It was the best thing one could do to be always cheerful.”

(Peter N. Stearns, Happiness in World History, 2020.)

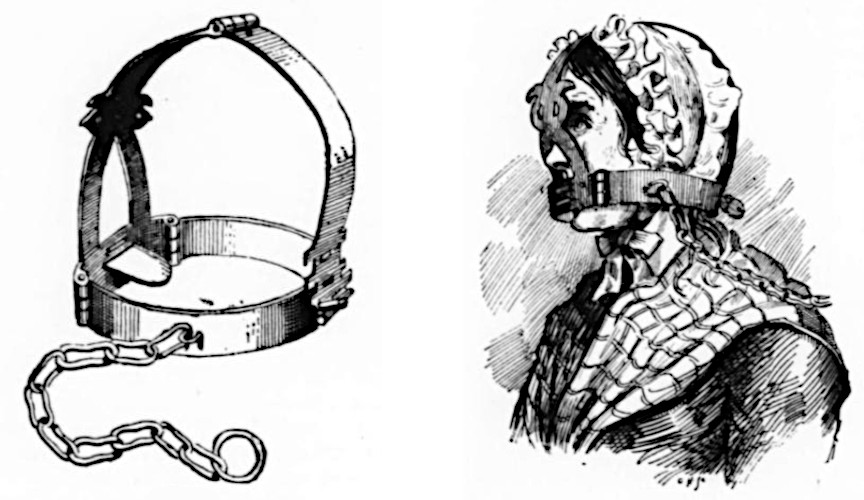

The brank consisted of a kind of crown or framework of iron, which was locked upon the head of the delinquent. It was armed in front with a gag, plate, point or knife of the same metal, which was fitted in such a manner as to be inserted in the scold’s mouth so as to prevent her moving her tongue; or, more cruel still, it was so placed that if she did move it, or attempt to speak, her tongue was cruelly lacerated, and her sufferings intensified. With this cage upon her head, and with the gag pressed and locked upon the tongue, the poor creature was paraded through the streets, led by the beadle or constable, or else she was chained to the pillory or market cross to be the object of scorn and derision, and to be subjected to all the insults and degradations that local loungers could invent.

— “Muzzles for Ladies,” Strand, November 1894

For myself, I must say that I find [Edward] Lear funniest when he is least arbitrary and when a touch of burlesque or perverted logic makes its appearance. … While the Pobble was in the water some unidentified creatures came and ate his toes off, and when he got home his aunt remarked:

‘It’s a fact the whole world knows,

That Pobbles are happier without their toes,’which once again is funny because it has a meaning, and one might even say a political significance. For the whole theory of authoritarian governments is summed up in the statement that Pobbles were happier without their toes.

— George Orwell, “Nonsense Poetry,” 1945

A Weak Man going down-hill met a Strong Man going up, and said:

‘I take this direction because it requires less exertion, not from choice. I pray you, sir, assist me to regain the summit.’

‘Gladly,’ said the Strong Man, his face illuminated with the glory of his thought. ‘I have always considered my strength a sacred gift in trust for my fellow-men. I will take you up with me. Go behind me and push.’

— Ambrose Bierce, Fantastic Fables, 1899