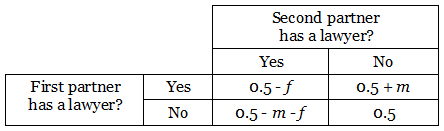

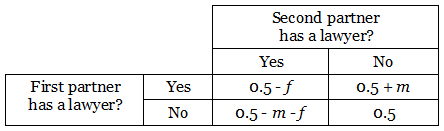

If two people want to split up amicably, the easiest solution is to divide their assets equally, with each partner getting 0.5. But suppose that one partner goes to a lawyer who charges a fee f but promises to get more, by an amount m + f, leaving his client better off by the amount m. If this happens, then the second partner will get only 0.5 – m – f. If the second partner engages their own lawyer then the split is equal again, except that now the lawyers’ fees must be paid:

This is an example of the so-called prisoner’s dilemma: Both sides would be better off if they left the lawyers out of it, but if one engages a lawyer than the other had better do so as well.

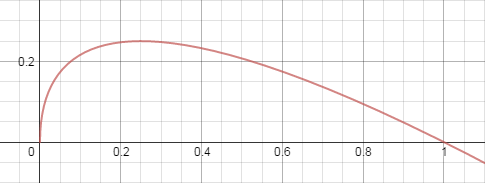

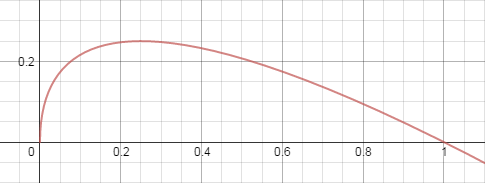

Now suppose that each partner can choose the amount of lawyer time to buy, and that they get a payoff that’s proportional to the amount they spend. If one spends x on lawyers and the other spends y, each measured as a fraction of the total assets, then the first partner should receive an amount given by:

An industrious divorcee can now use calculus to maximize this expression, varying x and keeping y constant. The optimum value of x turns out to be  . If my partner spends 9%, or 0.09, of our assets on lawyers, then I should spend

. If my partner spends 9%, or 0.09, of our assets on lawyers, then I should spend  . Then my partner will get 0.21 of the assets, and I’ll get 0.49, and the lawyers get the rest.

. Then my partner will get 0.21 of the assets, and I’ll get 0.49, and the lawyers get the rest.

Well, now what? Knowing all this, what’s our best course? If we could trust each other then we’d each pay a pittance on lawyers and get nearly 0.5 each. But I’m aware that if you pay a millionth and I pay a thousandth (still nearly a pittance), I’ll get nearly 99.9% of our assets. And simply resolving to outspend you won’t work: If you spend 0.36 then I should spend 0.24; I’ll come away with less than you, but this is the best I can do.

“Looking at the graph of  , above, we (the author and reader) see that y = 0.25 gives us x = 0.25, and this gives us a sort of stability,” writes Anthony C. Robin in the Mathematical Gazette. “Neither partner can pull a fast one over the other, and it results in the assets being equally shared between us, them, and the lawyers. No doubt this is the reason why lawyers are so rich in our society!”

, above, we (the author and reader) see that y = 0.25 gives us x = 0.25, and this gives us a sort of stability,” writes Anthony C. Robin in the Mathematical Gazette. “Neither partner can pull a fast one over the other, and it results in the assets being equally shared between us, them, and the lawyers. No doubt this is the reason why lawyers are so rich in our society!”

(Anthony C. Robin, “How Lawyers Make a Living,” Mathematical Gazette 88:512 [July 2004], 313-315.)