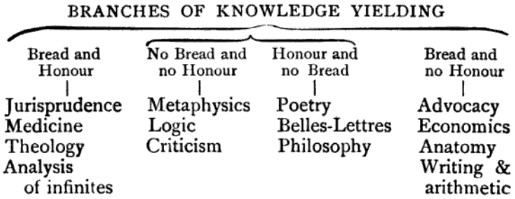

In his Reflections, Georg Christoph Lichtenberg mentions a friend who divided human endeavor into four classes:

In his Reflections, Georg Christoph Lichtenberg mentions a friend who divided human endeavor into four classes:

quisquous

adj. difficult to deal with or settle

quillet

n. a verbal nicety, a subtle distinction

aggiornamento

n. the act of bringing something up to date to meet current needs

irenic

adj. fitted or designed to promote peace

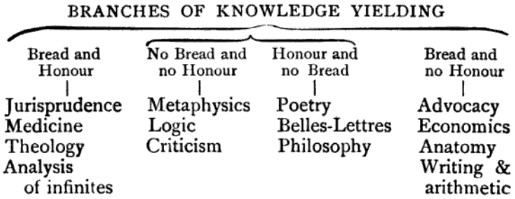

The survivors of the Titanic were picked up by the English passenger steamship Carpathia, which conveyed them to New York. This presented a delicate problem to the Social Register. “In those days the ship that people travelled on was an important yardstick in measuring their standing, and the Register dutifully kept track,” notes Walter Lord in A Night to Remember (1955). “To say that listed families crossed on the Titanic gave them their social due, but it wasn’t true. To say they arrived on the plodding Carpathia was true, but socially misleading. How to handle this dilemma? In the case of those lost, the Register dodged the problem — after their names it simply noted the words, ‘died at sea, 15 April 1912’. In the case of those living, the Register carefully ran the phrase, ‘Arrived Titan-Carpath, 18 April 1912’. The hyphen represented history’s greatest sea disaster.”

If mercy modifies the demands of justice, then to be merciful is perhaps to be unjust. But manifesting injustice is a vice, not a virtue. This seems to mean that mercy is a vice. A sentencing judge has been hired to enforce the rule of law that society has agreed upon. If he tempers this, even through love or compassion, then arguably he’s departing from his sworn obligation. Angelo says in Measure for Measure:

I show [pity] most of all when I show justice,

For then I pity those I do not know,

Which a dismissed offense would after gall,

And do him right that, answering one foul wrong,

Lives not to act another.

(If we try to claim that mercy is a form of justice, so that every act of mercy is just, then we’re saying that one has a right to mercy, that it’s not a gift. That seems wrong too.)

(Jeffrie G. Murphy and Jean Hampton, Forgiveness and Mercy, 1988, via George W. Rainbolt, “Mercy: An Independent, Imperfect Virtue,” American Philosophical Quarterly 27:2 [April 1990], 169-173.)

The beginnings of Algebra I found far more difficult [than Euclid], perhaps as a result of bad teaching. I was made to learn by heart: ‘The square of the sum of two numbers is equal to the sum of their squares increased by twice their product.’ I had not the vaguest idea what this meant, and when I could not remember the words, my tutor threw the book at my head, which did not stimulate my intellect in any way.

Utopian socialist Robert Owen opposed corporal punishment, so when he took over the textile mill at New Lanark, Scotland, in 1800, he kept order with a “silent monitor”: Over each worker’s machine was hung a block whose successive sides were painted white, yellow, blue, and black:

The 2,500 toys had their positions arranged every day, according to the conduct of each worker during the preceding day: white indicating superexcellence; yellow, moderate goodness; blue, a neutral condition of morals; and black, exceeding naughtiness.

These ratings were assigned by the departmental overseer, whose own rating was assigned by an under-manager. The final say lay with Owen, to whom workers could appeal, and the daily ratings were recorded in a “book of character” maintained by each department.

This sounds draconian, but combined with Owen’s generous nature it seemed to work. “As time went on,” wrote one biographer, “the yellows and whites gained on the darker hues; and in the later stages of Owen’s management the signs were almost entirely white, with a sprinkling of yellows.”

One night in 1939, Wolcott Gibbs’ 4-year-old son Tony began chanting a song in the bathtub. It was sung “entirely on one note except that the voice drops on the last word in every line”:

He will just do nothing at all.

He will just sit there in the noonday sun.

And when they speak to him, he will not answer them,

Because he does not care to.

He will stick them with spears and throw them in the garbage.

When they tell him to eat his dinner, he will just laugh at them.

And he will not take his nap, because he does not care to.

He will not talk to them, he will not say nothing.

He will just sit there in the noonday sun.

He will go away and play with the Panda.

He will not speak to nobody because he doesn’t have to.

And when they come to look for him they will not find him.

Because he will not be there.

He will put spikes in their eyes and put them in the garbage.

And put the cover on.

He will not go out in the fresh air or eat his vegetables.

Or make wee-wee for them, and he will get thin as a marble.

He will do nothing at all.

He will just sit there in the noonday sun.

Pete Seeger liked this so much that he made a song of it — he called it “Declaration of Independence”:

Chinese proverbs:

And “Learning is like paddling a canoe against the current — you will regress if you don’t advance.”

Tennyson was plagued by autograph hunters.

As a pretext, one wrote to him asking which was the better dictionary, Webster’s or Ogilvie’s.

He replied by cutting the word Ogilvie’s from the letter, pasting it to a blank sheet of paper, and mailing it back.

See Pen Fatigue.

By substituting images for claims, the pictorial commercial made emotional appeal, not tests of truth, the basis of consumer decisions. The distance between rationality and advertising is now so wide that it is difficult to remember that there once existed a connection between them. Today, on television commercials, propositions are as scarce as unattractive people. The truth or falsity of an advertiser’s claim is simply not an issue. A McDonald’s commercial, for example, is not a series of testable, logically ordered assertions. It is a drama — a mythology, if you will — of handsome people selling, buying and eating hamburgers, and being driven to near ecstasy by their good fortune. No claims are made, except those the viewer projects onto or infers from the drama. One can like or dislike a television commercial, of course. But one cannot refute it.

— Neil Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death, 1985

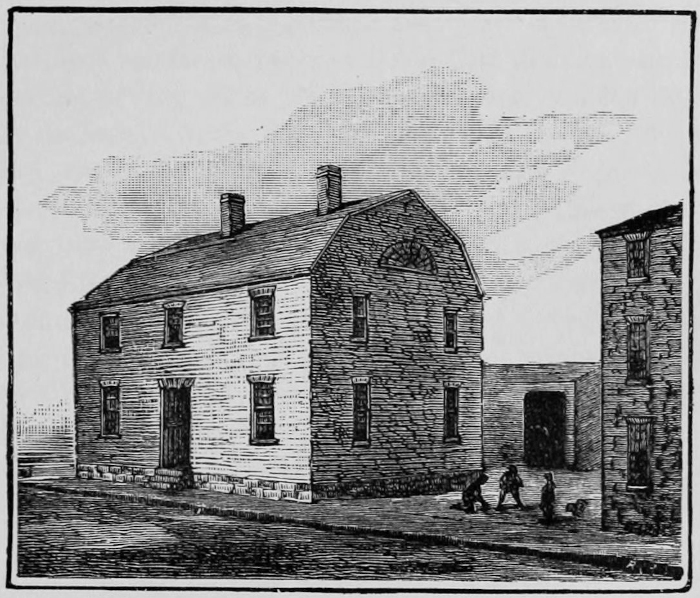

The Massachusetts School Law of 1642 declared ignorance to be a satanic ill:

It being one chief project of that old deluder, Satan, to keep men from the knowledge of the Scriptures, as in former times by keeping them in an unknown tongue, so in these latter times by persuading from the use of tongues, that so that at least the true sense and meaning of the original might be clouded and corrupted with love and false glosses of saint-seeming deceivers; [we resolve] that learning may not be buried in the grave of our forefathers, in church and commonwealth, the Lord assisting our endeavors.

It ordered every town of more than 50 families to hire a teacher and every town of more than 100 families to establish a grammar school, an early step toward public education in the United States.