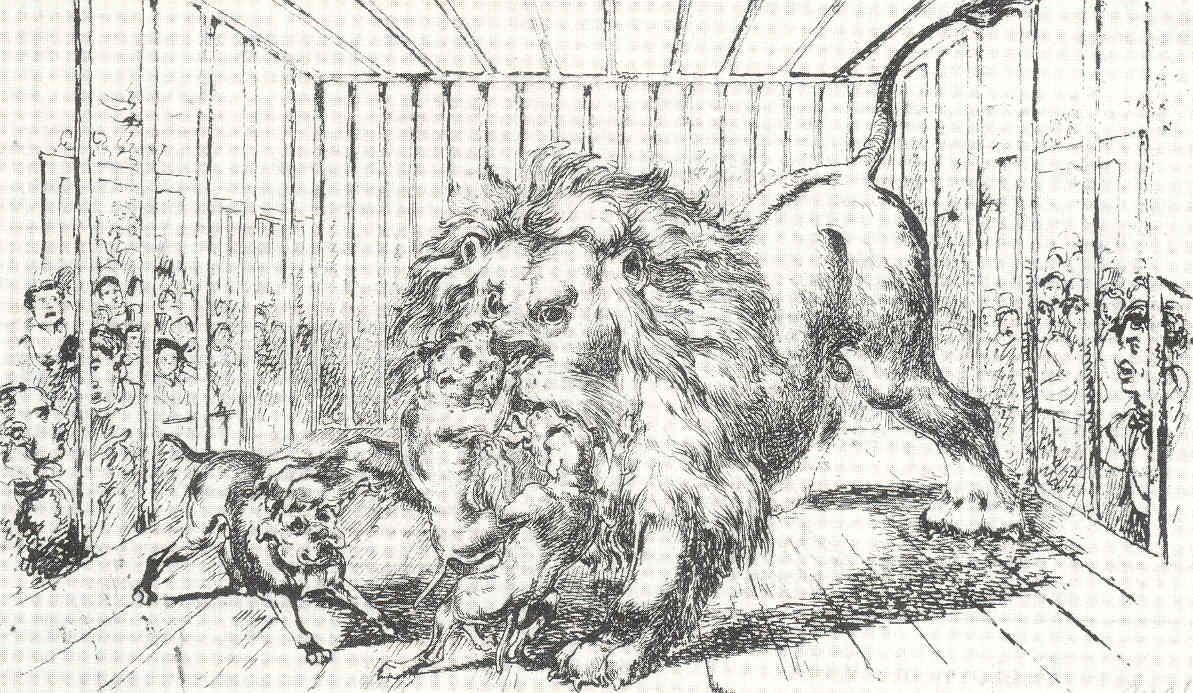

In 1825, impresario George Wombwell sponsored a fight between six bulldogs and a lion from his menagerie in the English market town of Warwick. Five hundred people assembled in a disused factory yard, and Wombwell arranged for the dogs to attack Nero three at a time, ignoring the pleas of a Quaker named Samuel Hoare, who asked “how thou wilt feel to see the noble animal thou hast so long protected, and which has been in part the means of supplying thee with the means of life, mangled and bleeding before thee?” The lion seemed indisposed to use its full strength against the first three dogs, swatting them away with his paws but never biting. After a 20-minute respite, Wombwell set the next three dogs upon him, and they pinned him to the floor. When a third round brought the same result, Wombwell conceded defeat for the lion, afraid that “the death of the animal must be the consequence of further punishment.”

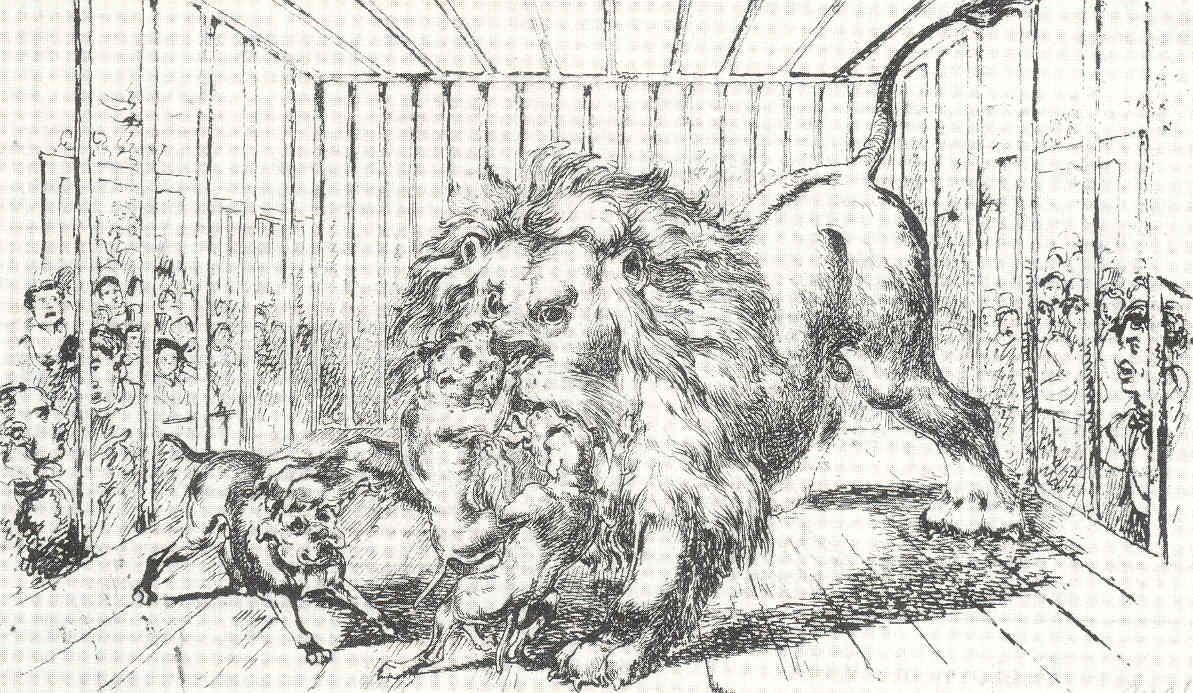

In a second contest less than a week later, though, a Scottish-born lion known as Wallace fought back ferociously, holding one dog in his teeth and “deliberately walk[ing] around the stage with him as a cat would a mouse.” A second dog “died just a few seconds after he was taken out of the cage,” and a third remained in Wallace’s jaws until a keeper “threw a piece of raw flesh into the den.” A fourth was left in critical condition with “several of his ribs broken.”

The spectacle was widely condemned in the press and informed a new sensitivity regarding cruelty to animals. In 1838 one commentator remarked, “what dogs and lions can achieve in the arena of combat … having now been ascertained, let us hope that no closer approximation to the sanguinary games of the Roman amphitheatre may ever be attempted in Great Britain, nor her soil again polluted by a repetition of such spectacles.”

(Helen Cowie, “A Disgusting Exhibition of Brutality,” in Sarah Cockram and Andrew Wells, eds., Interspecies Interactions, 2018.)