anfractuous

adj. having many windings and turnings

loof

n. the palm of the hand

penetralia

n. the innermost recesses of a building

swither

n. a state of perplexity

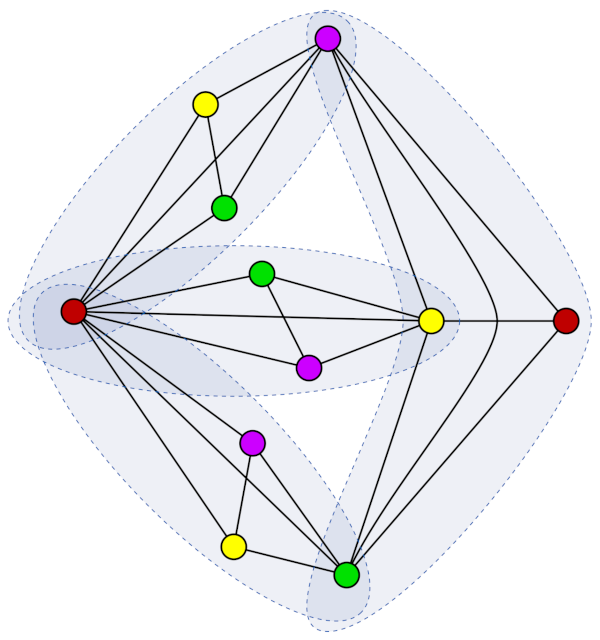

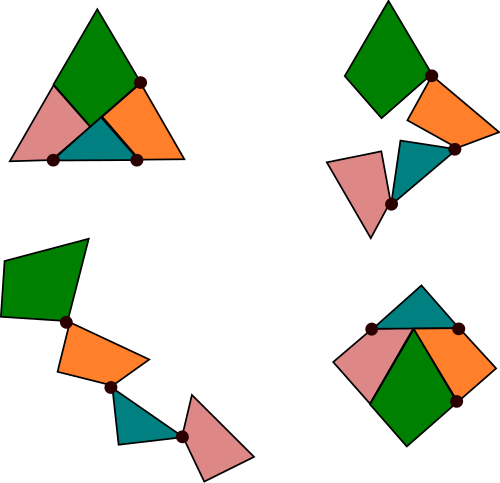

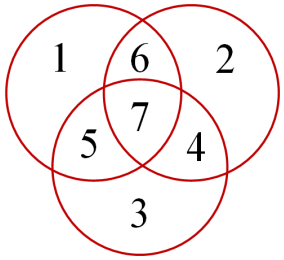

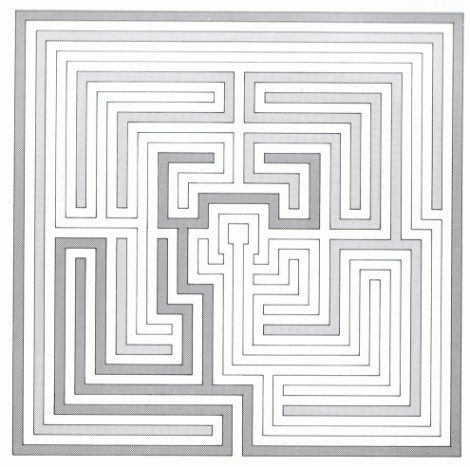

It’s commonly said that you can defeat a hedge maze by placing one hand on a wall and carefully maintaining that contact as you advance. If the hedges are all connected, this method will reliably lead you to the center of the maze (and, indeed, to every other part of it before you return to the entrance).

The Chevening maze, in Kent, was designed deliberately to thwart this technique. Its center is concealed in an “island” of hedges distinct from the outer wall, so following either a left- or a right-hand rule will return you to the entrance without ever passing the goal.