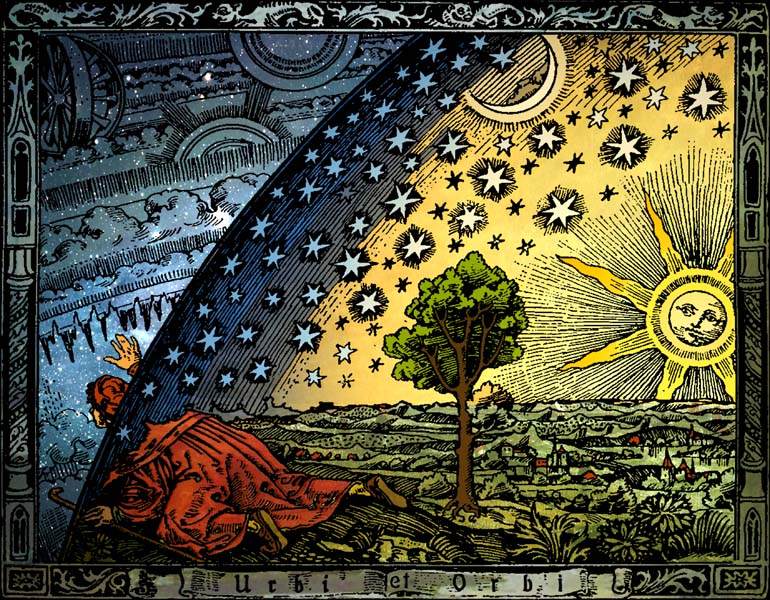

A striking tale from the 18th century: It’s said that around 1687 a group of English mariners on the Italian coast were surprised to see “two men run by us with amazing swiftness”:

Captain Barnaby says, ‘Lord bless me, the foremost man looks like next door neighbour, old Booty;’ but said he did not know the other behind. Booty was dressed in grey clothes, and the one behind him in black; we saw them run into the burning mountain in the midst of the flames! on which we heard a terrible noise, too horrible to be described.

When they returned to Gravesend, Captain Barnaby’s wife said, “My dear, I have got some news to tell you; old Booty is dead.” Barnaby swore an oath and said, “We all saw him run into Hell!”

As the story goes, when word of this allegation reached Booty’s widow, she sued Barnaby for a thousand pounds. The punchline is that Booty’s appearance on the volcano was shown to have occurred within two minutes of his death, and when his coat was exhibited in the courtroom, 12 sailors swore that its buttons matched those of the fleeing man.

The Judge then said, ‘Lord grant I may never see the sight that you have seen; one, two, or three may be mistaken, but twenty or thirty cannot.’ So the widow lost her cause.

According to folklorist Jeremy Harte, this story appeared in print at least 19 times between the 1770s and the 1830s. It seems to have started among the dockyards of the lower Thames, where in one early version Booty was an unscrupulous contractor who had supplied the navy with adulterated beer — and his damnation was “a matter of just retribution for the sin he had committed.”

(Jeremy Harte, “Into the Burning Mountain: Legend, Literature, and Law in Booty v. Barnaby,” Folklore 125:3 [December 2014], 322-338.)