Virginia Centurione Bracelli died in 1651, but her body was found largely uncorrupted when her grave was opened 150 years later.

She was canonized in 2003.

Virginia Centurione Bracelli died in 1651, but her body was found largely uncorrupted when her grave was opened 150 years later.

She was canonized in 2003.

Whilst sitting quietly in [Bank House], the inmates have been frequently alarmed — sometimes two or three times a day — by the descent of showers of water, apparently from the ceiling. These showers have drenched them, flooding the floor and covering the furniture with water, rendering the house almost uninhabitable. … The water comes straight down from the ceiling, and shows not the slightest indication of its being thrown into the apartment. So singular is the affair that people have concluded that it is some spiritual influence, and is a sort of judgment upon the good ladies of the house for some dereliction, who, naturally enough, are much affrighted.

— Preston Herald, Feb. 15, 1873

There’s a sculpture of Darth Vader on Washington’s National Cathedral.

During construction, a competition was held among children to suggest a carved grotesque, and Christopher Rader of Kearney, Neb., submitted a drawing of Darth Vader’s head.

It’s visible on the cathedral’s northwest tower — but you’ll need binoculars to see it.

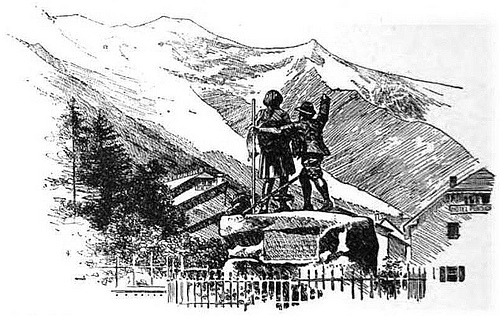

In August 1820, an avalanche swept three mountaineers into a crevasse on Mont Blanc. Thirty-eight years later, a physicist who had studied the glacier’s rate of flow predicted that the bodies would soon be given up. He was right. William Herbert Hobbs writes in Earth Features and Their Meaning:

In the year 1861, or forty-one years after the disaster, the heads of the three guides, separated from their bodies, with some hands and fragments of clothing, appeared at the foot of the Glacier des Bossons, and in such a state of preservation that they were easily recognized by a guide who had known them in life.

The bodies had traveled 3,000 meters in 41 years. “To-day,” wrote Hobbs in 1912, “the time of reappearance of portions of the bodies of persons lost upon Mont Blanc is rather accurately predicted, so that friends repair to Chamonix to await the giving up of its victims by the Glacier des Bossons.”

Near the village of Combe-Hay, in England, there was a wood composed largely of oaks and nut trees. In the middle of it was a field, about fifty yards long, in which six sheep were struck dead by lightning. When skinned there was discovered on them, on the inside of the skin, a facsimile of part of the adjacent landscape.

— William Walsh, A Handy Book of Curious Information, 1913

The body of a child, nine months old, was buried in the ‘Old Burying-Ground,’ Stoddard, N. H., in January, 1818. In 1856, the body was disinterred, with others adjacent to it, for the purpose of removal to another lot. The body of this child alone had petrified. It was nearly as white as marble, and the features were as natural as the day it was buried, though the body soon crumbled on being exposed to the air.

— Miscellaneous Notes and Queries, February 1888

Mark Twain wrote, “Water, taken in moderation, cannot hurt anybody.”

He would have approved of Matthew Robinson, the second Baron Rokeby. Born in 1712, the Scottish nobleman swam in the sea in all weather, sometimes until he fainted, and had drinking fountains installed along his route to the beach.

A visitor noted, “He was accustomed to bestow a few half-crown pieces … on any water drinkers he might happen to find partaking of his favorite beverage, which he never failed to recommend with peculiar force and persuasion.”

Not content with the sea, Robinson eventually even added a glass-enclosed swimming pool to his mansion, where he spent hours.

It doesn’t seem to have hurt him. He shunned physicians, but lived to be 88.

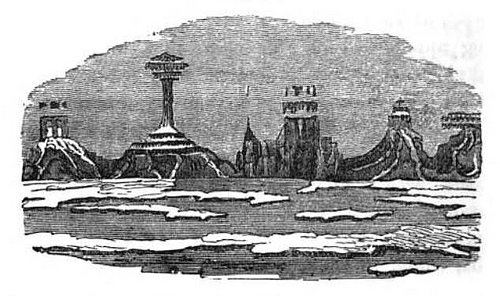

Observing the shore of Greenland in July 1820, explorer William Scoresby was surprised to see it change before his eyes:

The general telescopic appearance of the coast was that of an extensive ancient city abounding with the ruins of castles, obelisks, churches and monuments, with other large and conspicuous buildings. Some of the hills seemed to be surmounted by turrets, battlements, spires, and pinnacles; while others, subjected to one or two reflections, exhibited large masses of rock, apparently suspended in the air, at a considerable elevation above the actual termination of the mountains to which they referred.

All of this was continually changing even as he watched, Scoresby writes. But “notwithstanding these repeated changes, the various figures represented in the drawing had all the distinctness of reality; and not only the different strata, but also the veins of the rocks, with the wreaths of snow occupying ravines and fissures, formed sharp and distinct lines, and exhibited every appearance of the most perfect solidity.”

On the 18th of December, 1795, several persons, near the house of Captain Topham, in Yorkshire, heard a loud noise in the air, followed by a hissing sound, and soon after felt a shock, as if a heavy body had fallen to the ground at a little distance from them. In reality, one of them saw a huge stone fall to the earth, at the distance of eight or nine yards from the place where he stood. When he first observed it, it was seven or eight yards above the ground; and in its fall, it threw up the mould on every side, burying itself twenty-one inches in the earth. This stone, on being dug up, was found to weigh 56 lbs.

— Cabinet of Curiosities, Natural, Artificial, and Historical, 1822

Mr. Brograve, of Hamel, near Puckridge in Hertfordshire, when he was a young man, riding in a lane in that county, had a blow given him on his cheek: (or head) he looked back and saw that nobody was near behind him; anon he had such another blow, I have forgot if a third. He turned back, and fell to the study of the law; and was afterwards a Judge. This account I had from Sir John Penruddocke of Compton-Chamberlain, (our neighbour) whose Lady was Judge Brograve’s niece.

— John Aubrey, Miscellanies Upon Various Subjects, 1696