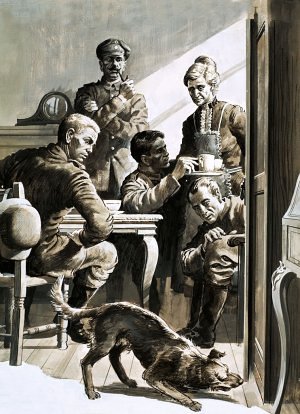

Brothers Alphonse, Kenneth, and Mayo Prud’homme were playing with a foot-long toy cannon in Natchitoches, La., in September 1941 when they saw a man peering at them through binoculars from the opposite side of the Cane River. “We just fired a shot at him to see what would happen,” Kenneth remembered later. “He bailed out of the tree and went flying back down the road in a cloud of dust.”

Presently the man returned with infantry. “They started shooting back at us, and when they’d shoot, we’d shoot back.”

This went on for half an hour, escalating gradually. The boys’ father added firecrackers to their arsenal; their opponents set up smoke screens and readied a .155 howitzer. At last an Army officer appeared at their side and said, “Mr. Prud’homme, do you mind calling off your boys? You’re holding up our war.”

The boys, ages 14, 12, and 9, had interrupted war games involving 400,000 troops spread over 3,400 square miles in preparation for America’s entry into World War II. At the sound of the cannon, George S. Patton had stopped his Blue convoy and engaged what he thought was the opposing Red army. His men were firing blanks, but the maneuvers were real.

“That’s my one claim to fame,” Kenneth told an Army magazine writer in 2009. “I defeated General Patton.”