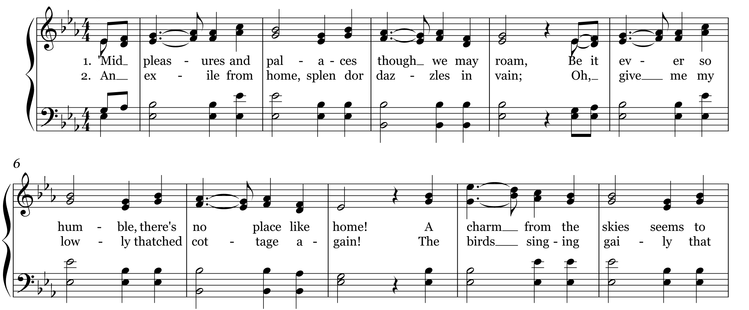

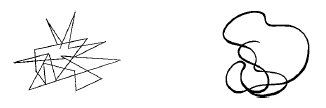

In a 1946 essay, Warner Brothers animator Chuck Jones presented two shapes:

These represent two nonsense words, tackety and goloomb. Which is which? Most people decide immediately that the shape on the left is tackety — even though that word has no meaning.

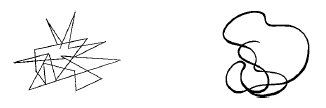

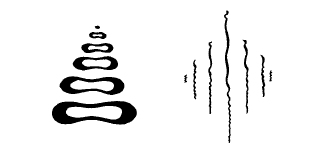

Similarly, one of these shapes is a bassoon, and one is a harp:

Here again, the correspondence seems obvious. “These are static examples of what are mostly static sounds,” Jones wrote. “The art of animation brings them to life, brings them fluidity and power; endows them, in short, with the qualities of music. The field of graphic symbols is a great but highly unexplored field. It will, I believe, prove an important one to the musician, and to any audience that is interested in satisfying the visual appetite, side by side with the auditory appetite.”

German-American psychologist Wolfgang Köhler had considered the same question in 1929. It’s been documented as “the bouba/kiki effect.”

(Chuck Jones, “Music and the Animated Cartoon,” Hollywood Quarterly 1:4 [1946], 364-370.)