In 18 years and 5 months (May 1810 to October 1828), Franz Schubert composed more than 1,000 works. And that’s counting complex pieces, such as operas, suites of dances for piano or orchestra, and song cycles numbering up to 24 individual items, as single compositions. From Harold Schonberg’s Lives of the Great Composers:

[Leopold von] Sonnleithner reports that ‘at Fräulein Fröhlich’s request, Franz Grillparzer had written for the occasion the beautiful poem Ständchen, and this she gave to Schubert, asking him to set it to music as a serenade for her sister Josefine (mezzo-soprano) and women’s chorus. Schubert took the poem, went into an alcove by the window, read it through carefully a few times and then said with a smile, “I’ve got it already, it’s done, and it’s going to be quite good.”‘ [Joseph von] Spaun tells of the composition of the Erlkönig. He and [Johann] Mayrhofer visited Schubert and found him reading the poem. ‘He paced up and down several times with the book, suddenly he sat down, and in no time at all (just as quickly as you can write) there was the glorious ballad finished on the paper. We ran with it to the Seminary, for there was no piano at Schubert’s, and there, on the very same evening, the Erlkönig was sung and enthusiastically received.’

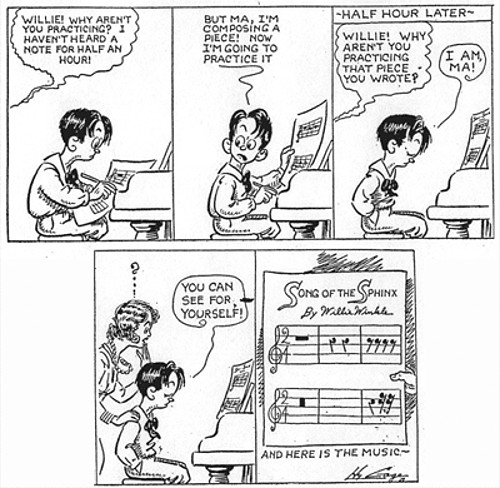

When he worked, he worked feverishly. The poet Franz von Schober said, “If you go to see him during the day, he says ‘Hello, how are you? — Good!’ and goes on working, whereupon you go away.”