Western Illinois University mathematician Iraj Kalantari published an unusual puzzle in Math Horizons in February 2019. A sphere B of radius 150 is centered at (150, 150, 0). A sphere M of radius 144, centered on the z-axis, lies entirely below the (x, y)-plane so that the volume of its intersection with B is 1/2. “Can we find a sphere S of radius 73 that has its center on the circle (x – 73)2 + (y – 73)2 = 1502 in the plane z = 73 so that the volume of B minus its intersections with M and S equals the volume of M minus its intersection with B plus the volume of S minus its intersection with B?”

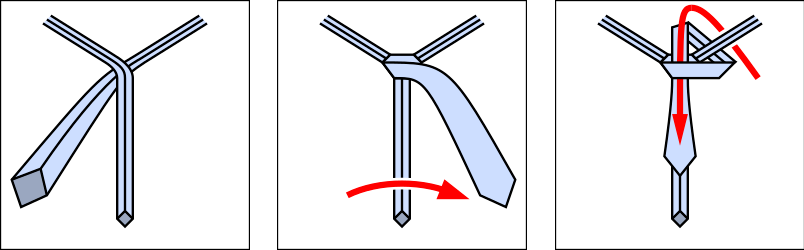

The answer is no, because Vol(B – (M ∪ S)) = Vol((M – B) ∪ (S – B)) if and only if Vol(B) = Vol(M) + Vol(S), and that’s the case if and only if  , where rB, rM, and rS are the radii of the three spheres. “[A]nd because the radii are integers, this equality is impossible by Fermat’s last theorem!”

, where rB, rM, and rS are the radii of the three spheres. “[A]nd because the radii are integers, this equality is impossible by Fermat’s last theorem!”

The placement of the spheres and the fact that the values differ by 1 are red herrings.

(Iraj Kalantari, “The Three Spheres,” Math Horizons 26:3 [February 2019]: 13, 25.)

02/28/2026 UPDATE: In my original statement of the problem I left out a vital phrase in Kalantari’s presentation: The sphere S should have its center on the circle (x – 73)2 + (y – 73)2 = 1502 in the plane z = 73.

I’d omitted the last phrase, a condition that guarantees that S lies above the xy plane and so does not intersect sphere M, which is required to deduce the equation involving the volumes. Many thanks to reader Francesco Veneziano for pointing this out.