Halfway between Hawaii and the mainland United States, there’s a vortex of ocean currents where plastic flotsam accumulates.

It’s known as the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch” — and it’s the size of Texas.

Halfway between Hawaii and the mainland United States, there’s a vortex of ocean currents where plastic flotsam accumulates.

It’s known as the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch” — and it’s the size of Texas.

The Duke de Saint Simon mentions in his ‘Memoirs’ a singular instance of constitutional sympathy between two brothers. These were twins — the President de Banquemore and the Governor de Bergues, who were surprisingly alike, not only in their persons, but in their feelings. One morning, he tells us, when the president was at his royal audience, he was suddenly attacked by an intense pain in the thigh; at the same instant, as it was discovered afterwards, his brother, who was with the army, received a severe wound from a sword on the same leg, and precisely the same part of the leg.

— Frank H. Stauffer, The Queer, the Quaint and the Quizzical, 1882

Abraham Lincoln’s son Robert seemed to carry an odd curse — he was present or nearby at three successive presidential assassinations:

In 1863, a stranger saved his life in a Jersey City train station. The stranger was Edwin Booth — the brother of John Wilkes Booth, his father’s future assassin.

In October 1928, newlyweds Glen and Bessie Hyde set out to run the rapids of the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon. They didn’t reappear by December, and a search plane spotted their scow adrift on the river, upright, intact, and loaded with supplies. No one knows what became of them.

English mathematician John Wallis (1616-1703) had an odd way of passing time:

“I note that on 22 December, 1669, he, when in bed, occupied himself in finding (mentally) the integral part of the square root of 3 × 1040; and several hours afterwards wrote down the result from memory. This fact having attracted notice, two months later he was challenged to extract the square root of a number of fifty-three digits; this he performed mentally, and a month later he dictated the answer, which he had not meantime committed to writing.”

— W.W. Rouse Ball, Mathematical Recreations & Essays, 1892

Mr. Samuel Leffers, of the county of Carteret, in North Carolina, had been attacked with a palsy in the face, and particularly in the eyes. While he was walking in his chamber, a thunderstroke threw him down senseless. At the end of twenty minutes he came to himself; but he did not recover the entire use of his limbs till the evening. Next day he found himself perfectly recovered; and he could now write without the use of spectacles. The palsy did not return.

— The Cabinet of Curiosities, 1824

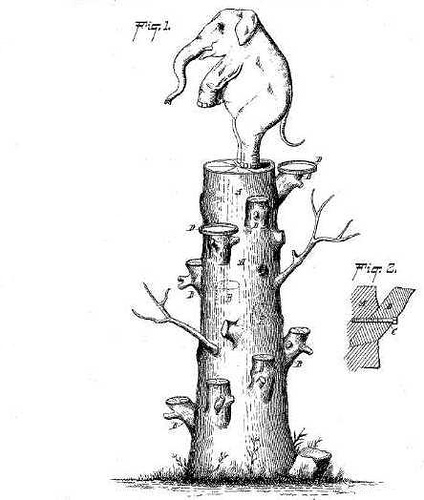

In 1891, Hermann Reiche patented a platform “to enable an elephant to climb up a tree.”

“Doubt,” wrote Galileo, “is the father of invention.”

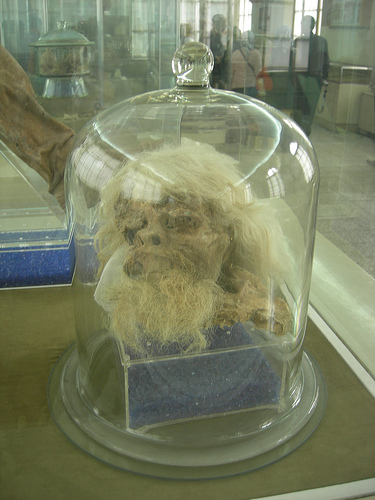

In winter 1993 workers in a salt mine in western Iran uncovered the body of a man with long hair and a beard. He had been buried in the middle of a 45-meter tunnel.

Carbon dating showed he had been lying there for 1700 years. It appears he was of high rank and had been struck in the head, but no one knows who he was or how he came to be there.

See also Bog Bodies.

The world’s longest-lived light bulb is in a fire station in Livermore, Calif.

It’s been burning continuously since 1901.

In March 1781, the Continental Navy sloop Saratoga was escorting a convoy of merchant ships off Haiti when it spotted two British sails to the west. It overtook and captured the first ship, put an American crew aboard, and set out after the second.

Midshipman Penfield, commander of that crew, was watching the chase when a strong wind arose, requiring his attention. When he raised his eyes again, the Saratoga had vanished. No trace of her was ever found.