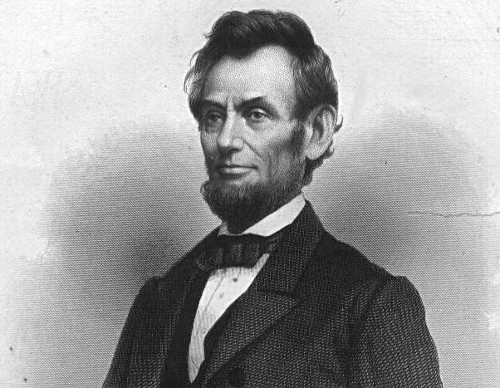

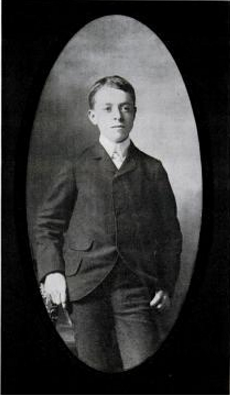

On Sept. 26, 1901, 13-year-old Fleetwood Lindley was attending school in Springfield, Ill., when his teacher handed him a note: His father wanted him urgently. He rode his bicycle to the Oak Ridge cemetery two miles out of town and found his father, Joseph, in the memorial hall of Abraham Lincoln’s tomb. The assassinated president, now 36 years dead, was being transferred to a new resting place, and a small group of caretakers had decided to open his coffin to confirm his identity.

The casket had been laid across a pair of sawhorses. A pair of workmen used a blowtorch to unseal the lead panel that covered Lincoln’s upper body, and the small group peered in.

Afterward the coffin was lowered into a hole 10 feet deep, encased in a cage of steel bars, and buried under tons of concrete. Over the years, as the other witnesses passed away, Lindley became the last living person to have looked on Lincoln’s body.

“His face was chalky white,” he remembered for a Life reporter in 1963, three days before his own death. “His clothes were mildewed. And I was allowed to hold one of the leather straps as we lowered the casket for the concrete to be poured.”

“I was not scared at the time, but I slept with Lincoln for the next six months.”