Kermit the Frog spoke at ventriloquist Edgar Bergen’s funeral.

Search Results for: in a word

In Other Words

Twins Grace and Virginia Kennedy were severely neglected by their San Diego parents, attended minimally by a German-speaking grandmother. They saw no other children, rarely played outdoors, and did not go to school.

They were 8 years old when a speech therapist realized they had invented their own language:

GRACE: Cabengo, padem manibadu peeta.

VIRGINIA: Doan nee bada tengkmatt, Poto.

It was apparently a mix of English and German, with some original words and grammatical oddities.

Their father soon forbade their speaking it, saying, “You live in a society, you got to speak the language.” They learned English, but they still bear the emotional scars of their neglect: Virginia works on an assembly line, and Grace mops floors at a fast-food restaurant.

A Good Word

Words dropped since the 1901 edition of the Chambers Dictionary:

- decacuminated adj. having the top cut off

- effodient adj. habitually digging (zoology)

- essorant adj. about to soar

- flipe v. to fold back, as a sleeve

- lectual adj. confining to the bed

- neogamist n. a person recently married

- nuciform adj. nut-shaped

- numerotage n. the numbering of yarns so as to denote their fineness

- pantogogue n. a medicine once believed capable of purging away all morbid humours

- parageusia n. a perverted sense of taste

- presultor n. the leader of a dance

- ramollescence n. softening, mollifying

- roytish adj. wild, irregular

- sagesse n. wisdom

- salebrous adj. rough, rugged

- sammy v. to moisten skins with water

- sarn n. a pavement

- scavilones n. men’s drawers worn in the sixteenth century under the hose

- tarabooka n. a drumlike instrument

- tortulous adj. having swellings at regular intervals

- wappet n. a yelping cur

Famous Last Words

While completing his last movie, James Dean filmed a safe-driving announcement aimed at teenagers.

“The life you save,” he concluded, “may be mine.”

A Word to the Wise

“Servants are a necessary evil. He who shall contrive to obviate their necessity, or remove their inconveniences, will render to human comfort a greater benefit than has yet been conferred by all the useful-knowledge societies of the age. They are domestic spies, who continually embarrass the intercourse of the members of a family, or possess themselves of private information that renders their presence hateful, and their absence dangerous. It is a rare thing to see persons who are not controlled by their servants. Theirs, too, is not the only kitchen cabinet which begins by serving and ends by ruling.”

— From The Laws of Etiquette, by “A Gentleman,” 1836

Longest English Word

The longest word in the English language is FLOCCINAUCINIHILIPILIFICATION.

It means “the act of estimating (something) as worthless.”

Words With Early Pedigrees

Surprisingly old words:

- SPACESHIP (first print use: 1894)

- ACID RAIN (1858)

- HAIRDRESSER (1771)

- ANTACID (1753)

- HAS-BEEN (1606)

- EARTHLING (1593)

- MILKY WAY (ca. 1384, even earlier in Latin)

Amazingly, light beer (“leoht beor”) first shows up around the year 1000.

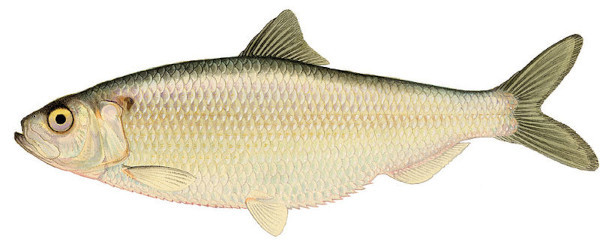

Shining Sea

Early European colonists were staggered at the abundance of fish in the Chesapeake Bay. William Byrd II wrote in his natural history of Virginia:

Herring are not as large as the European ones, but better and more delicious. When they spawn, all streams and waters are completely filled with them, and one might believe, when he sees such terrible amounts of them, that there was as great a supply of herring as there is water. In a word, it is unbelievable, indeed, indescribable, as also incomprehensible, what quantity is found there. One must behold oneself.

More accounts here. “The abundance of oysters is incredible,” marveled Swiss explorer Francis Louis Michel in 1701. “There are whole banks of them so that the ships must avoid them. A sloop, which was to land us at Kingscreek, struck an oyster bed, where we had to wait about two hours for the tide.”

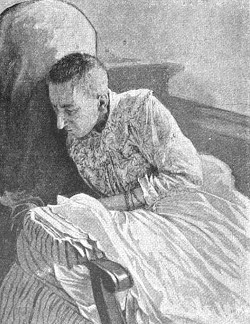

Blanche Monnier

In May 1901, the attorney general of Paris received an anonymous letter. It read, “I have the honor to inform you of an exceptionally serious occurrence. I speak of a spinster who is locked up in Madame Monnier’s house, half-starved and living on a putrid litter for the past twenty-five years — in a word, in her own filth.”

When police investigated, they found in Monnier’s attic a 52-year-old woman who weighed barely 25 kilograms. One policeman described the scene: “The unfortunate woman was lying completely naked on a rotten straw mattress. All around her was formed a sort of crust made from excrement, fragments of meat, vegetables, fish, and rotten bread. … We also saw oyster shells, and bugs running across Mademoiselle Monnier’s bed. The air was so unbreathable, the odor given off by the room was so rank, that it was impossible for us to stay any longer to proceed with our investigation.”

In 1874, when Blanche was 25, her mother Louise had locked her away to prevent her marrying a “penniless lawyer,” and for 25 years she and Blanche’s brother had pretended that she had disappeared. Louise was arrested but died shortly afterward; the brother was convicted but acquitted on appeal. Blanche was admitted to a psychiatric hospital but died in 1913. The identity of the letter writer who revealed all this was never discovered.

A Closer Look

Michael Snow’s 1967 experimental film Wavelength consists essentially of an extraordinarily slow 45-minute zoom on a photograph on the wall of a room. William C. Wees of McGill University points out that this raises a philosophical question: What visual event does this zoom create? In a tracking shot, the camera moves physically forward, and its viewpoint changes as a person’s would as she advanced toward the photo. In Wavelength (or any zoom) the camera doesn’t move, and yet something is taking place, something with no analogue in ordinary experience.

“If I actually walk toward a photograph pinned on a wall, I find that the photograph does, indeed, get larger in my visual field, and that things around it slip out of view at the peripheries of my vision. The zoom produces equivalent effects, hence the tendency to describe it as ‘moving forward.’ But I am really imitating a tracking shot, not a zoom. … I think it is safe to say that no perceptual experience in the every-day world can prepare us for the kind of vision produced by the zoom.”

“What, in a word, happens during a viewing of that forty-five minute zoom? And what does it mean?”

(From Nick Hall, The Zoom: Drama at the Touch of a Lever, 2018.)