An invertible word made of impossible letters, by Basile Morin:

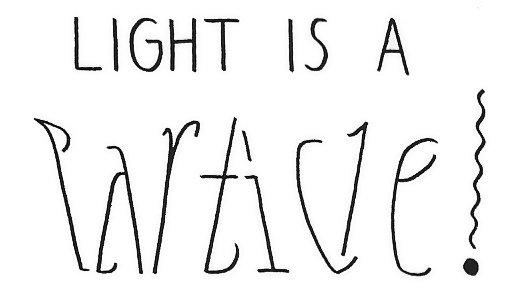

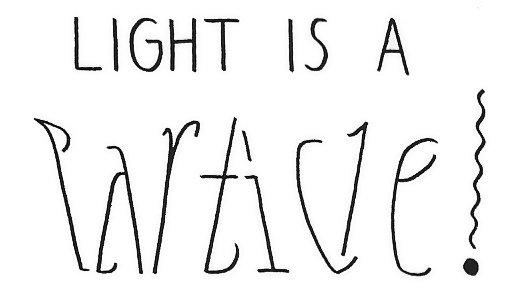

An emphatic assertion by Douglas Hofstadter:

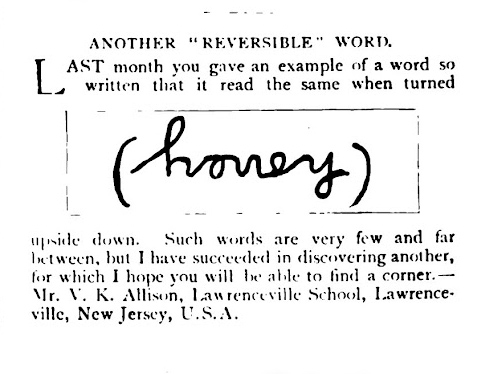

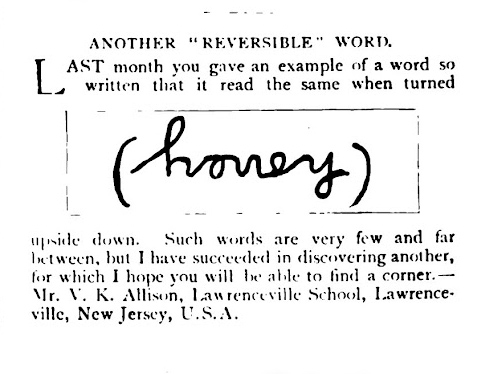

In 1908, after observing that chump in cursive reads largely the same upside down, the Strand asked for similar specimens and received this:

An invertible word made of impossible letters, by Basile Morin:

An emphatic assertion by Douglas Hofstadter:

In 1908, after observing that chump in cursive reads largely the same upside down, the Strand asked for similar specimens and received this:

Paris newspapers once carried an ad offering a cheap and pleasant way of travelling for the price of 25 centimes. Several simpletons mailed this sum. Each received a letter of the following content:

‘Sir, rest at peace in bed and remember that the earth turns. At the 49th parallel — that of Paris — you travel more than 25,000 km a day. Should you want a nice view, draw your curtain aside and admire the starry sky.’

The man who sent these letters was found and tried for fraud. The story goes that after quietly listening to the verdict and paying the fine demanded, the culprit struck a theatrical pose and solemnly declared, repeating Galileo’s famous words: ‘It turns.’

— Yakov Perelman, Physics for Entertainment, 1913

Kevin Purbhoo invented this vivid puzzle while a student at Northern Secondary School in Toronto:

On a remote Norwegian mountain top, there is a huge checkerboard, 1000 squares wide and 1000 squares long, surrounded by steep cliffs to the north, south, east, and west. Each square is marked with an arrow pointing in one of the eight compass directions, so (with the possible exception of some squares on the edges) each square has an arrow pointing to one of its eight nearest neighbors. The arrows on squares sharing an edge differ by at most 45 degrees. A lemming is placed randomly on one of the squares, and it jumps from square to square following the arrows. Prove that the poor creature will eventually plunge from a cliff to its death.

Occasionally, by coincidence, the gaps between words on a page of printed text will become aligned, producing “rivers” of white space that descend across multiple lines. These occur most commonly when the font is monospaced and justification is full. Because they’re distracting, these artifacts are generally discouraged; typographers sometimes view a printed page upside down in order to spot them.

In ordinary text long rivers are unlikely, but in 1988 Mark Isaak found the 12-line example above on page 277 of the Harvard Classics edition of Darwin’s The Voyage of the Beagle (squint to see it).

Fritzi Striebel offered a small collection of unusual rivers at the end of this article in the May 1986 issue of Word Ways.

What do you call a person from Connecticut? Today we’d call them a Connecticuter or a Connecticutian (or, colloquially, a Nutmegger), but in a 1987 address etymologist Allen Walker Read announced that he’d also found these options:

He also found several jocular forms:

“Especially in language, exuberance accounts for much that happens.”

(Allen Walker Read, “Exuberance, a Motivation for Language,” (Word Ways 21:2 [May 1988], 71-74. He gives his documentation in “What Connecticut People Can Call Themselves,” Connecticut Onomastic Review No. 2, 1981, 3-23. In 1992 he took up the same question regarding “Americans.”)

A man of the State of Chêng was one day gathering fuel, when he came across a startled deer, which he pursued and killed. Fearing lest any one should see him, he hastily concealed the carcass in a ditch and covered it with plantain leaves, rejoicing excessively at his good fortune. By and by, he forgot the place where he had put it, and, thinking he must have been dreaming, he set off towards home, humming over the affair on his way.

Meanwhile, a man who had overheard his words, acted upon them, and went and got the deer. The latter, when he reached his house, told his wife, saying, ‘A woodman dreamt he had got a deer, but he did not know where it was. Now I have got the deer; so his dream was a reality.’ ‘It is you,’ replied his wife, ‘who have been dreaming you saw a woodman. Did he get the deer? and is there really such a person? It is you who have got the deer: how, then, can his dream be a reality?’ ‘It is true,’ assented the husband, ‘that I have got the deer. It is therefore of little importance whether the woodman dreamt the deer or I dreamt the woodman.’

Now when the woodman reached his home, he became much annoyed at the loss of the deer; and in the night he actually dreamt where the deer then was, and who had got it. So next morning he proceeded to the place indicated in his dream, — and there it was. He then took legal steps to recover possession; and when the case came on, the magistrate delivered the following judgment:– ‘The plaintiff began with a real deer and an alleged dream. He now comes forward with a real dream and an alleged deer. The defendant really got the deer which plaintiff said he dreamt, and is now trying to keep it; while, according to his wife, both the woodman and the deer are but the figments of a dream, so that no one got the deer at all. However, here is a deer, which you had better divide between you.’

— Herbert Allen Giles, A History of Chinese Literature, 1927

On April 1, 1990, an anonymous verse was posted to the comp.lang.perl newsgroup on Usenet. It was written in the programming language Perl 3:

BEFOREHAND: close door, each window & exit; wait until time.

open spellbook, study, read (scan, select, tell us);

write it, print the hex while each watches,

reverse its length, write again;

kill spiders, pop them, chop, split, kill them.

unlink arms, shift, wait & listen (listening, wait),

sort the flock (then, warn the "goats" & kill the "sheep");

kill them, dump qualms, shift moralities,

values aside, each one;

die sheep! die to reverse the system

you accept (reject, respect);

next step,

kill the next sacrifice, each sacrifice,

wait, redo ritual until "all the spirits are pleased";

do it ("as they say").

do it(*everyone***must***participate***in***forbidden**s*e*x*).

return last victim; package body;

exit crypt (time, times & "half a time") & close it,

select (quickly) & warn your next victim;

AFTERWORDS: tell nobody.

wait, wait until time;

wait until next year, next decade;

sleep, sleep, die yourself,

die at last

Because of the large number of English words that are used in the Perl language, the poem can actually be compiled as legal code and executed as a program. (It exits on line one, reaching the function exit, producing no output.)

The poem was attributed to “a person who wishes to remain anonymous,” but new “Perl poems” are regularly submitted to the programming community at PerlMonks.

In March 1939, students at McGill University dictated this sentence to a dozen faculty members:

Outside a cemetery sat a harassed cobbler and an embarrassed oculist, picknicking on a desiccated apple, and gazing at the symmetry of a lady’s ankle with unparalleled ecstasy.

The participants included three English professors, the head of the journalism department, and a proofreading instructor.

Only Esther Korstad, instructor of typewriting and shorthand, spelled everything correctly. The average participant misspelled 4.25 words.

An episode from P.T. Barnum’s childhood in Bethel, Connecticut:

‘What is the price of razor strops?’ inquired my grandfather of a peddler, whose wagon, loaded with Yankee notions, stood in front of our store.

‘A dollar each for Pomeroy’s strops,’ responded the itinerant merchant.

‘A dollar apiece!’ exclaimed my grandfather; ‘they’ll be sold for half the money before the year is out.’

‘If one of Pomeroy’s strops is sold for fifty cents within a year, I’ll make you a present of one,’ replied the peddler.

‘I’ll purchase one on those conditions. Now, Ben, I call you to witness the contract,’ said my grandfather, addressing himself to Esquire Hoyt.

‘All right,’ responded Ben.

‘Yes,’ said the peddler, ‘I’ll do as I say, and there’s no backout to me.’

My grandfather took the strop, and put it in his side coat pocket.

Presently drawing it out, and turning to Esquire Hoyt, he said, ‘Ben, I don’t much like this strop now I have bought it. How much will you give for it?’

‘Well, I guess, seeing it’s you, I’ll give fifty cents,’ drawled the ‘Squire, with a wicked twinkle in his eye, which said that the strop and the peddler were both incontinently sold.

‘You can take it. I guess I’ll get along with my old one a spell longer,’ said my grandfather, giving the peddler a knowing look.

The strop changed hands, and the peddler exclaimed, ‘I acknowledge, gentlemen; what’s to pay?’

‘Treat the company, and confess you are taken in, or else give me a strop,’ replied my grandfather.

‘I never will confess nor treat,’ said the peddler, ‘but I’ll give you a strop for your wit;’ and suiting the action to the word, he handed a second strop to his customer. A hearty laugh ensued, in which the peddler joined.

‘Some pretty sharp fellows here in Bethel,’ said a bystander, addressing the peddler.

‘Tolerable, but nothing to brag of,’ replied the peddler; ‘I have made seventy-five cents by the operation.’

‘How is that?’ was the inquiry.

‘I have received a dollar for two strops which cost me only twelve and a half cents each,’ replied the peddler; ‘but having heard of the cute tricks of the Bethel chaps, I thought I would look out for them and fix my prices accordingly. I generally sell these strops at twenty-five cents each, but, gentlemen, if you want any more at fifty cents apiece, I shall be happy to supply your whole village.’

Our neighbors laughed out of the other side of their mouths, but no more strops were purchased.

(From his 1855 autobiography.)