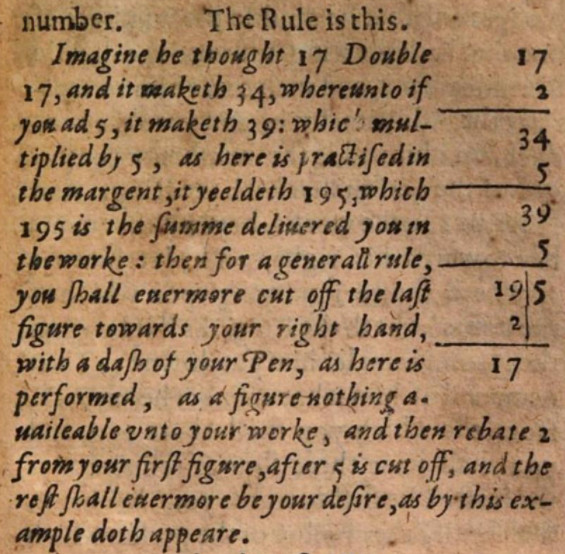

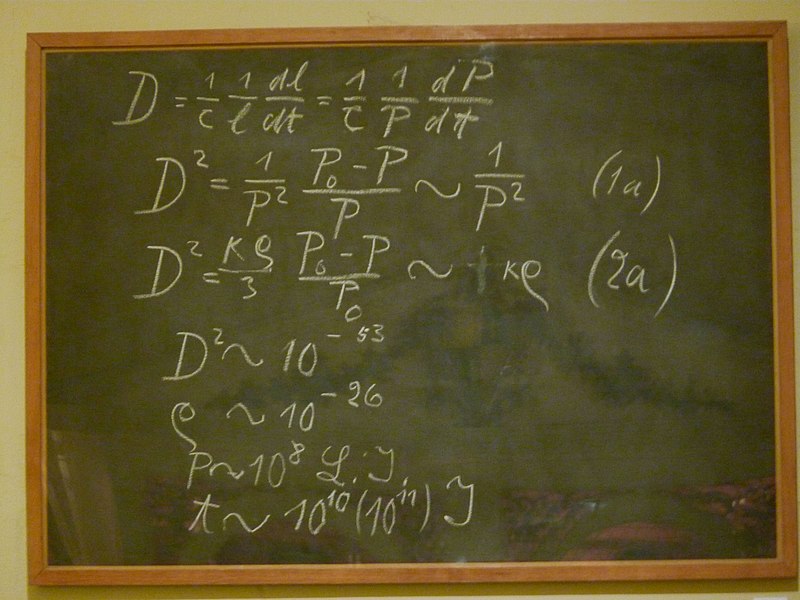

During a visit to Oxford in May 1931, Albert Einstein gave a brief lecture on cosmology, and afterward the blackboard was preserved along with Einstein’s ephemeral writing. It now resides in the university’s Museum of the History of Science.

Harvard historian of science Jean-François Gauvin argues that this makes it a “mutant object”: It’s no longer fulfilling the essential function of a blackboard, to store information temporarily — it’s become something else, a socially created object linked to the great scientist. The board’s original essence could be restored by wiping it clean, but that would destroy its current identity.

“The sociological metamorphosis at the origin of this celebrated artifact has completely destroyed its intrinsic nature,” Gauvin writes. “Einstein’s blackboard has become an object of memory, an object of collection modified at the ontological level by a social desire to celebrate the achievement of a great man.”