Inflexible

No letter appears twice in AMBIDEXTROUSLY.

Next!

History’s shortest-reigning king served for 20 minutes. When Charles X abdicated the French crown after the July Revolution of 1830, rule passed to his son, Louis XIX, who immediately resigned as well, over his wife’s entreaties.

The longest-reigning king is the pharaoh Pepi II, who ascended the Egyptian throne in 2278 B.C. at age 6. He ruled for 94 years.

The Eltanin Antenna

What is this? The oceanographic research ship USNS Eltanin discovered it off the Antarctic coast in 1964, at a depth of 13,500 feet — that’s 2.5 miles down.

It could be an alien ship buried under the seafloor. It could be ancient technology left by a forgotten civilization. It could be a well-hidden gift left by time travelers from the remote future.

Or it could be a sponge, Cladorhiza concrescens. You decide.

Unquote

“The great pleasure of a dog is that you may make a fool of yourself with him and not only will he not scold you, but he will make a fool of himself too.” — Samuel Butler

A Biblical Pangram

Ezra 7:21 contains every letter except J:

And I, even I, Artaxerxes the king, do make a decree to all the treasurers which are beyond the river, that whatsoever Ezra the priest, the scribe of the law of the God of heaven, shall require of you, it be done speedily.

Wait a Minute …

If you use Microsoft Windows, you’ve seen the Webdings and Wingdings fonts. They’re “dingbat” fonts — in place of letters they offer small clip-art images and symbols.

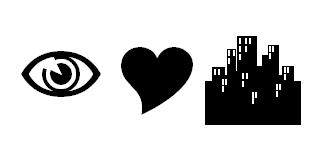

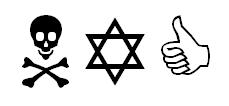

Well, here’s “NYC” in Webdings:

And here’s “NYC” in Wingdings:

Make of this what you will.

Math Notes

1634 = 14 + 64 + 34 + 44

Undisturbed

A remarkable discovery was made early in the last century at the Elizabethan manor house of Bourton-on-the-Water, Gloucestershire, only a portion of which remains incorporated in a modern structure. Upon removing some of the wallpaper of a passage on the second floor, the entrance to a room hitherto unknown was laid bare. It was a small apartment about eight feet square, and presented the appearance as if some occupant had just quitted it. A chair and a table within, each bore evidence of the last inmate. Over the back of the former hung a priest’s black cassock, carelessly flung there a century or more ago, while on the table stood an antique tea-pot, cup, and silver spoon, the very tea leaves crumbled to dust with age. On the same storey were two rooms known as ‘the chapel’ and the ‘priest’s room,’ the names of which signify the former use of the concealed apartment.

— Allan Fea, Secret Chambers and Hiding-Places, 1908

The Whitehall Mystery

Scotland Yard is built on the site of an unsolved murder.

The torso of a “well-nourished” 24-year-old woman was found in a cellar vault in October 1888, while the police service’s headquarters was being built in Westminster. Her arm had been discovered earlier on the bank of the Thames, and a reporter later discovered a leg elsewhere on the construction site.

The woman’s uterus was also missing, an unsettling echo of Jack the Ripper’s killings, which were terrorizing London at the same time. The Metropolitan Police said there was no connection.

The woman’s head and other limbs were never found, and her identity — and that of her killer — has never been established.