Feeling blue. Read more: https://t.co/S9YIoiIH3L #worldmentalhealthday pic.twitter.com/r6kG79EPbj

— World Economic Forum (@wef) October 10, 2018

Tokyo has the world’s busiest train stations, handling 13 billion passenger trips a year. To keep things running smoothly it relies on some subtle features to manipulate passenger behavior.

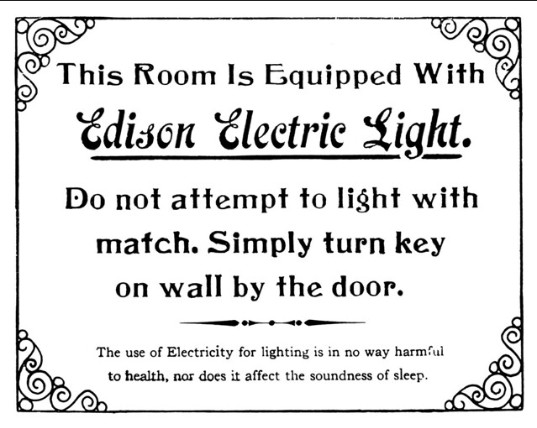

Blue lights mounted discreetly at either end of a platform, the points at which prospective suicides contemplate leaping into the path of oncoming trains, have been associated with an 84 percent decline in such attempts.

Rail operator JR East commissioned composer Hiroaki Ide to replace the grating buzzer that used to signal a train’s departure with short, pleasant jingles known as hassha melodies. These have produced a 25 percent reduction in passenger injuries due to rushing.

Stations also disperse young people by playing 17-kilohertz tones that can generally only be heard by those under 25. And rail employees are trained to use the “point and call” method, shisa kanko, in executing tasks. Physically pointing at an object and verbalizing one’s intentions has been shown to reduce human error by as much as 85 percent.

(Thanks, Sharon.)