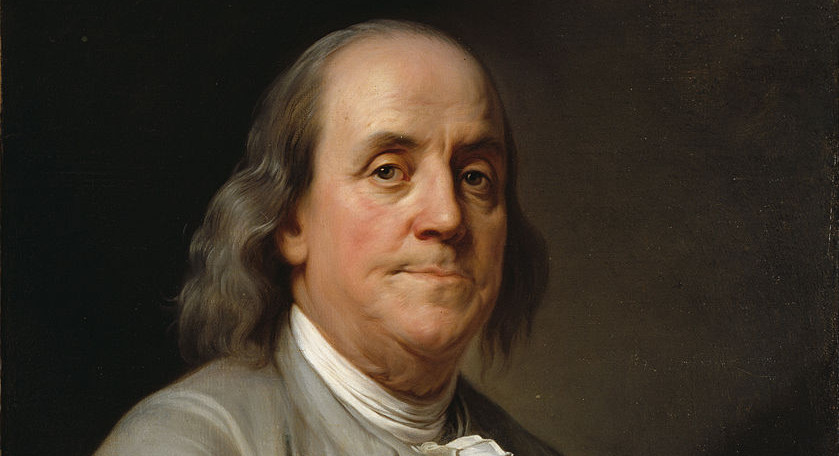

Questions put by Benjamin Franklin to his Junto, a club for mutual improvement that he founded in Philadelphia in 1727:

- How shall we judge of the goodness of a writing? Or what qualities should a writing have to be good and perfect in its kind? (His own answer: “It should be smooth, clear, and short.”)

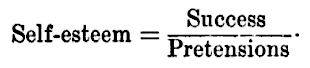

- Can a man arrive at perfection in this life, as some believe; or is it impossible, as others believe?

- Wherein consists the happiness of a rational creature?

- What is wisdom? (“The knowledge of what will be best for us on all occasions, and the best ways of attaining it.”)

- Is any man wise at all times and in all things? (“No, but some are more frequently wise than others.”)

- Whether those meats and drinks are not the best that contain nothing in their natural taste, nor have anything added by art, so pleasing as to induce us to eat or drink when we are not thirsty or hungry, or after thirst and hunger are satisfied; water, for instance, for drink, and bread or the like for meat?

- Is there any difference between knowledge and prudence? If there is any, which of the two is most eligible?

- Is it justifiable to put private men to death, for the sake of public safety or tranquillity, who have committed no crime? As, in the case of the plague, to stop infection; or as in the case of the Welshmen here executed?

- If the sovereign power attempts to deprive a subject of his right (or, which is the same thing, of what he thinks his right), is it justifiable in him to resist, if he is able?

- Which is best: to make a friend of a wise and good man that is poor or of a rich man that is neither wise nor good?

- Does it not, in a general way, require great study and intense application for a poor man to become rich and powerful, if he would do it without the forfeiture of honesty?

- Does it not require as much pains, study, and application to become truly wise and strictly virtuous as to become rich?

- Whence comes the dew that stands on the outside of a tankard that has cold water in it in the summer time?

From Carl Van Doren’s biography. “New members had to stand up with their hands on their breasts and say they loved mankind in general and truth for truth’s sake. … In time the Junto had so many applications for membership it was at a loss to know how to limit itself to the twelve originally planned.”