111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111

111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111

111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111

111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111

111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111

111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111

111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111

111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111

111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111

111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111

11111111111111111111111111111111111111111 is prime.

Science & Math

Market Forces

The following question was a favourite topic for discussion, and thousands of the acutest logicians, through more than one century, never resolved it: ‘When a hog is carried to market with a rope tied about its neck, which is held at the other end by a man, whether is the hog carried to market by the rope or the man?’

— Isaac Disraeli, Curiosities of Literature, 1893

The Misfortune Field

One of the most enduring contributions to the [Wolfgang] Pauli legend was the ‘Pauli Effect,’ according to which Pauli could, by his mere presence, cause laboratory accidents and catastrophes of all kinds. Peierls informs us that there are well-documented instances of Pauli’s appearance in a laboratory causing machines to break down, vacuum systems to spring leaks, and glass apparatus to shatter. Pauli’s destructive spell became so powerful that he was credited with causing an explosion in a Göttingen laboratory the instant his train stopped at the Göttingen station.

– William H. Cropper, Great Physicists, 2004

(To exaggerate the effect, Pauli’s friends once arranged to have a chandelier crash to the floor when he arrived at a reception. When he appeared, a pulley jammed, and the chandelier refused to budge.)

The Mirror Problem

In 1868, 8-year-old Alice Raikes was playing with friends in her London garden when a visitor at a neighbor’s house overheard her name and called to her.

“So you are another Alice,” he said. “I’m very fond of Alices. Would you like to come and see something which is rather puzzling?” He led them into a room with a tall mirror in one corner.

‘Now,’ he said, giving me an orange, ‘first tell me which hand you have got that in.’ ‘The right,’ I said. ‘Now,’ he said, ‘go and stand before that glass, and tell me which hand the little girl you see there has got it in.’ After some perplexed contemplation, I said, ‘The left hand.’ ‘Exactly,’ he said, ‘and how do you explain that?’ I couldn’t explain it, but seeing that some solution was expected, I ventured, ‘If I was on the other side of the glass, wouldn’t the orange still be in my right hand?’ I can remember his laugh. ‘Well done, little Alice,’ he said. ‘The best answer I’ve had yet.’

“I heard no more then, but in after years was told that he said that had given him his first idea for Through the Looking-Glass, a copy of which, together with each of his other books, he regularly sent me.”

Bootstraps Everlasting

I recently visited an Eastern sage and asked him, ‘Is it possible to live for ever?’ ‘Certainly,’ he replied, ‘You must undertake to do two things.’ ‘What are they?’ ‘Firstly, you must never again make any false statements.’ ‘That’s simple enough. What is the second thing I must do?’ ‘Every day you must utter the statement “I will repeat this statement tomorrow.” If you follow these instructions faithfully you are certain to live forever.’

— Jacqueline Harman, letter to the Daily Telegraph, Oct. 8, 1985

Misc

- Q is the only letter that does not appear in any U.S. state name.

- 6455 = (64 – 5) × 5

- North Dakota’s record high temperature (121°F) is higher than Florida’s (109°F).

- UNNOTICEABLY contains the vowels A, E, I, O, and U in reverse order.

- “An odd thought strikes me: We shall receive no letters in the grave.” — Samuel Johnson

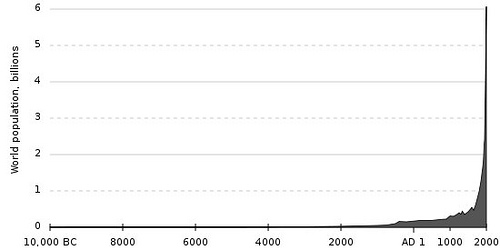

No Vacancy

The world population has doubled between:

- 1181 and 1715

- 1715 and 1881

- 1881 and 1960

- 1960 and 1999

It’s expected to reach 9 billion by 2040.

Pandigital Squares

Square numbers containing all 10 digits unrepeated:

320432 = 1026753849

322862 = 1042385796

331442 = 1098524736

351722 = 1237069584

391472 = 1532487609

456242 = 2081549376

554462 = 3074258916

687632 = 4728350169

839192 = 7042398561

990662 = 9814072356

The Mirror

From Albert Beiler, Recreations in the Theory of Numbers (1964):

1 + 4 + 5 + 5 + 6 + 9 = 3 + 2 + 3 + 7 + 8 + 7

Pair each digit on the left with one on the right (for example, 13, 42, 53, 57, 68, 97). The sum of these six numbers will always equal its mirror image:

13 + 42 + 53 + 57 + 68 + 97 = 79 + 86 + 75 + 35 + 24 + 31

This works for all 720 possible combinations.

Most remarkably, you can square every term in these equations and they still hold:

132 + 422 + 532 + 572 + 682 + 972 = 792 + 862 + 752 + 352 + 242 + 312

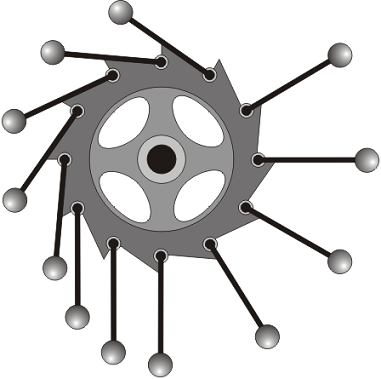

Perpetual Notion

The balls on the right exert greater torque than those on the left, so the wheel ought to turn forever, right?

Sadly, the balls on the left are more numerous.

“If at first you don’t succeed,” wrote Quentin Crisp, “failure may be your style.”