You and I each have a stack of coins. We agree to compare the coins atop our stacks and assign a reward according to the following rules:

- If head-head appears, I win $9 from you.

- If tail-tail appears, I win $1 from you.

- If head-tail or tail-head appears, you win $5 from me.

After the first round each of us discards his top coin, revealing the next coin in the stack, and we evaluate this new outcome according to the same rules. And so on, working our way down through the stacks.

This seems fair. There are four possible outcomes, all equally likely, and the payouts appear to be weighted so that in the long run we’ll both break even. But in fact you can arrange your stack so as to win 80 cents per round on average, no matter what I do.

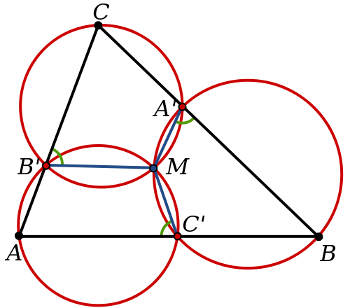

Let t represent the fraction of your coins that display heads. If my coins are all heads, then your gain is given by

GH = -9t + 5(1 – t) = -14t + 5.

If my coins are all tails, then your gain is

GT = +5t – 1(1 – t) = 6t – 1.

If we let GH = GT, we get t = 0.3, and you gain GH = GT = $0.80.

This result applies to an entire stack or to any intermediate segment, which means that it works even if my stack is a mix of heads and tails. If you arrange your stack so that 3/10 of the coins, randomly distributed in the stack, display heads, then in a long sequence of rounds you’ll win 80 cents per round, no matter how I arrange my own stack.

(From J.P. Marques de Sá, Chance: The Life of Games & the Game of Life, 2008.)