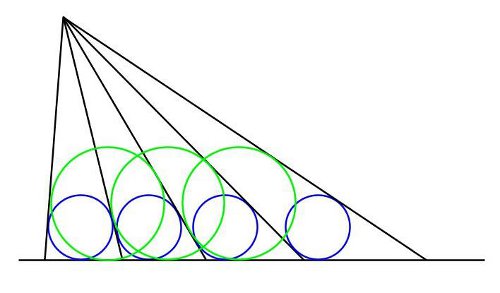

A Japanese geometry theorem from the Edo period: If the blue circles are equal, the green circles will be equal too.

This can be extended: Circles spanning three of these triangles will also be equal, and so on.

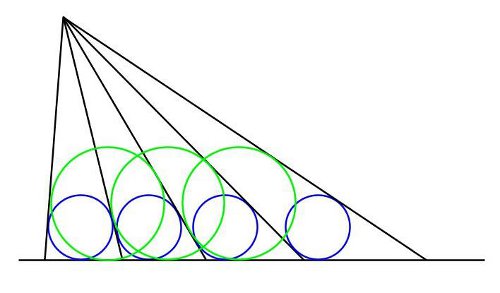

A Japanese geometry theorem from the Edo period: If the blue circles are equal, the green circles will be equal too.

This can be extended: Circles spanning three of these triangles will also be equal, and so on.

Jump into the sea and look up. The surface above you is dark except for a bright circle that follows you around like a portable skylight. This is Snell’s window: Because light is refracted as it enters the water, the 180-degree world above you is compressed into a tight 97 degrees.

Physicist Robert W. Wood was thinking of this effect when he created a new wide-angle lens in 1906. Fittingly, he called it the fisheye.

In 1990, Spanish philosopher Jon Perez Laraudogoitia submitted an article to Mind entitled “This Article Should Not Be Rejected by Mind.” In it, he argued:

They published it. “This is, I believe, the first article in the whole history of philosophy the content of which is concerned exclusively with its own self, or, in other words, which is totally self-referential,” Laraudogoitia wrote. “The reason why it is published is because in it there is a proof that it should not be rejected and that is all.”

In 1964 Canadian writer Graeme Gibson bought a parrot in Mexico. The bird, which Gibson named Harold Wilson, was bright and affectionate at first, but he seemed to grow lonely in the dark Canadian winter, so in the spring Gibson made arrangements to donate him to the Toronto Zoo. At the aviary Gibson carried Harold into the cage that had been prepared for him, placed him on a perch, said his goodbyes, and turned to go.

“Then Harold did something that astonished me. For the very first time, and in exactly the voice my kids might have used, he called out ‘Daddy!’ When I turned to look at him he was leaning towards me expectantly. ‘Daddy’, he repeated.

“I don’t remember what I said to him. Something about him being happier there, that he’d soon make friends. The kind of things you say to kids when you abandon them at camp. But outside the aviary I could still hear him calling ‘Daddy! Daddy!’ as we walked away. I was shattered to discover that Harold knew my name, and that he did so because he’d identified himself with my children.

“I now believe he’d known it all along, but was using it — for the first time — out of desperation. Both Konrad Lorenz and Bernd Heinrich mention instances of birds calling out the private names of intimates when threatened by serious danger. I am no longer surprised by such information. We think of our captive birds as our pets, but perhaps we are theirs as well.”

(From Gibson’s Perpetual Motion, 1982.)

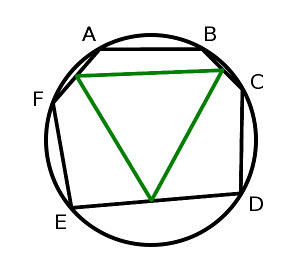

Inscribe a hexagon in a unit circle such that AB = CD = EF = 1.

Now the midpoints of BC, DE, and FA form an equilateral triangle.

See A Better Nature.

Arthur W.J.G. Ord-Hume calls this “the most graceful and simple perpetual motion machine of all time.” It was offered by American inventor F.G. Woodward in the 19th century. A heavy wheel is mounted between two rollers so that the wheel’s weight causes it to roll continuously in the direction of the arrow.

Or so Woodward hoped. Ord-Hume notes that the principle required the left half of the wheel always to be heavier than the right half. “Sadly, it wasn’t.”

How do I know that I’m not just a fictional character in some imagined story? What could I learn about myself that would prove that I’m real? “I am human, male, brunette, etc., but none of that helps,” writes UCLA philosopher Terence Parsons. “I see people, talk to them, etc., but so did Sherlock Holmes.”

Descartes would say that the very fact that I’m thinking about this shows that I exist: cogito ergo sum. But a fictional character could make the same argument. “Hamlet did think a great many things,” writes Jaakko Hintikka. “Does it follow that he existed?” Robert Nozick adds, “Could not any proof be written into a work of fiction and be presented by one of the characters, perhaps one named ‘Descartes’?”

Tweedledee tells Alice that she’s only a figment of the Red King’s dream. “If that there King was to wake,” adds Tweedledum, “you’d go out — bang! — just like a candle!”

Alice says, “Hush! You’ll be waking him, I’m afraid, if you make so much noise.”

“Well, it’s no use YOUR talking about waking him,” replies Tweedledum, “when you’re only one of the things in his dream. You know very well you’re not real.”

“It seems to me that this is a philosophical problem that deserves to be treated seriously on a par with issues like the reality of the external world and the existence of other minds,” Parsons writes. “I don’t know how to solve it.”

(Terence Parsons, Nonexistent Objects, 1980; Charles Crittenden, Unreality, 1991; Robert Nozick, “Fiction,” Ploughshares 6:3 [1980], 74-78; Jaakko Hintikka, “Cogito, Ergo Sum: Inference or Performance?”, Philosophical Review 71:1 [January 1962], 3-32.)

If a flock of birds disperses gradually, at what point does it cease to be a flock?

“There is at the moment a pipe on my desk,” wrote MIT philosopher Richard Cartwright in 1987. “Its stem has been removed, but it remains a pipe for all that; otherwise no pipe could survive a thorough cleaning.”

But he also owned a two-volume set of John McTaggart’s The Nature of Existence, one volume of which was in Cambridge and the other in Boston. Do those two volumes still make one thing? If so, is there a “thing” composed of the Eiffel Tower and the Old North Church? Why not?

(From Cartwright’s Philosophical Essays.)

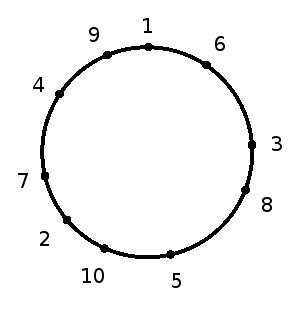

Draw a circle whose circumference is the golden mean. Choose a point and label it 1, then move clockwise around the circle in steps of arc length 1, labeling the points 2, 3, and so on. At each step, the difference between each pair of adjacent numbers on the circle is a Fibonacci number.

When Montenegro declared independence from Yugoslavia, its top-level domain changed from .yu to .me.