W.H. Auden won first prize for mathematics at St. Edmund’s School in Hindhead, Surrey, when he was 13. He recalled being asked to learn the following mnemonic around 1919:

Minus times Minus equals Plus;

The reason for this we need not discuss.

W.H. Auden won first prize for mathematics at St. Edmund’s School in Hindhead, Surrey, when he was 13. He recalled being asked to learn the following mnemonic around 1919:

Minus times Minus equals Plus;

The reason for this we need not discuss.

1 + 2 = 3

1×2 + 2×3 + 3×4 = 4×5

1×2×3 + 2×3×4 + 3×4×5 + 4×5×6 = 5×6×7

1×2×3×4 + 2×3×4×5 + 3×4×5×6 + 4×5×6×7 + 5×6×7×8 = 6×7×8×9

In general, the sum of the first (n+1) products of consecutive n-tuples of consecutive integers is equal to the product of the next n-tuple.

(Thanks, Peter.)

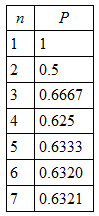

Suppose n students are sitting at n desks in a classroom. They’re asked to stand, mill around at random, and then sit again. What is the probability that at least one student will find herself in her original seat?

Intuition says that the probability ought to drop as the number of students increases, but in fact it remains about the same:

In fact, Pierre Rémond de Montmort showed in 1708 that it’s

… which approaches 1 – 1/e, or about 0.63212. Whether there are 10 students or 10,000, the chance that at least one student returns to her own seat is about 2/3.

Antoni Zygmund once asked if the World Series shouldn’t be called the World Sequence? And shouldn’t a combination lock be called a permutation lock? John Von Neumann once had a dog called Inverse. It would sit when told to stand and go when it was told to come. Von Neumann pronounced the term infinite series as infinite serious.

— Michael Stueben, Twenty Years Before the Blackboard, 1998

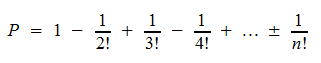

Starting in the 1970s, neurobiologist Otto-Joachim Grüsser spent 10 years collating the light sources in 2,124 paintings selected at random from Western art originating between the 14th and 20th centuries. He found that in most paintings considered Western works of art, especially those painted around the time of the Scientific Revolution, the light falls from the left.

“At the beginning of modern Western art during the early Gothic period, a preference for diffuse illumination or light sources distributed around the painted scene was found,” Grüsser noted. “In a minority of paintings from the fourteenth century that show a clear light direction, a bias to the left side is present. This left-sided preference increased at the expense of diffuse or middle light sources up to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and declined thereafter. In the twentieth century, the diffuse or middle type of light distribution again became dominant.”

It’s not clear what to make of this. It seems reasonable that a right-handed artist might favor light falling from the left, but why should this vary with time? Grüsser found that the left-handed Leonardo da Vinci applied light sources from varying angles, and Hans Holbein the Younger, also a dominant left-hander, favored light falling from the right.

“From such observations in the works of these two left-handed painters who painted, drew, and wrote with the left hand, one gains the impression that the distribution of left, middle, and right light direction in left-handed painters deviates significantly from the average distribution of light found in the paintings of other contemporary painters. It would be interesting to study the drawings and paintings of other confirmed left-handed artists, who worked exclusively with the left hand.”

(Otto-Joachim Grüsser, Thomas Selke, and Barbara Zynda, “Cerebral Lateralization and Some Implications for Art, Aesthetic Perception, and Artistic Creativity,” in Ingo Rentschler, Barbara Herzberger, and David Epstein, Beauty and the Brain, 1988.)

Suppose you have three identical Dewar flasks labeled A, B, and C. (A Thermos is a Dewar flask.) You also have an empty container labeled D, which has thermally perfect conducting walls and which fits inside a Dewar flask.

Pour 1 liter of 80°C water into flask A and 1 liter of 20°C water into flask B. Now, using all four containers, is it possible to use the hot water to heat the cold water so that the final temperature of the cold water is higher than the final temperature of the hot water? How? (You can’t actually mix the hot water with the cold.)

Timothy and Urban are playing a game with two six-sided dice. The dice are unusual: Rather than bearing a number, each face is painted either red or blue.

The two take turns throwing the dice. Timothy wins if the two top faces are the same color, and Urban wins if they’re different. Their chances of winning are equal.

The first die has 5 red faces and 1 blue face. What are the colors on the second die?

Discovered by R.V. Heath in 1950:

Think of two positive integers.

Add them to get a third number.

Add the second number and the third number to get a fourth number.

Continue in this way until you have 10 numbers.

The sum of the 10 numbers is 11 times the seventh number.

Mathematician Yutaka Nishiyama of the Osaka University of Economics has designed a nifty paper boomerang that you can use indoors. A free PDF template (with instructions in 70 languages!) is here.

Hold it vertically, like a paper airplane, and throw it straight ahead at eye level, snapping your wrist as you release it. The greater the spin, the better the performance. It should travel 3-4 meters in a circle and return in 1-2 seconds. Catch it between your palms.

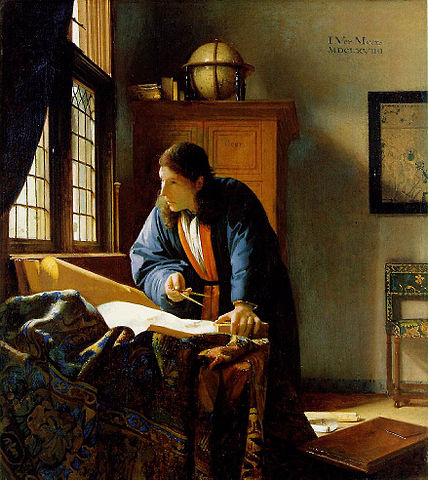

By 1958 many of the attributes of living things could be found in our technology: locomotion (cars), metabolism (steam engines), energy storage (batteries), perception of stimuli (iconoscopes), and nervous or cerebral activity (computers). The missing element was reproduction: We hadn’t yet created a nonliving artifact that could make copies of itself.

So Brooklyn College chemistry professor Homer Jacobson built one. Using an HO gauge model railroad, he designed an “organism” made of boxcars that could use sensors to select other cars on the track and assemble them on a siding into models of itself. “Head” cars have “brains,” and “tail” cars have “muscles” and “eyes”; together, a head and a tail make an organism in which the head directs the tail to watch for available cars elsewhere on the track and shunt them appropriately onto a siding to create a new organism.

“Any new ‘organisms’ formed continue the propagation in a linear fashion,” Jacobson wrote, “until the environment runs out of parts, or there are no more sidings available, or a mistake is made somewhere in the operation of a cycle, i.e., a ‘mutation.’ Such an effect, like that with living beings, is usually fatal.”

(Homer Jacobson, “On Models of Reproduction,” American Scientist, September 1958.)