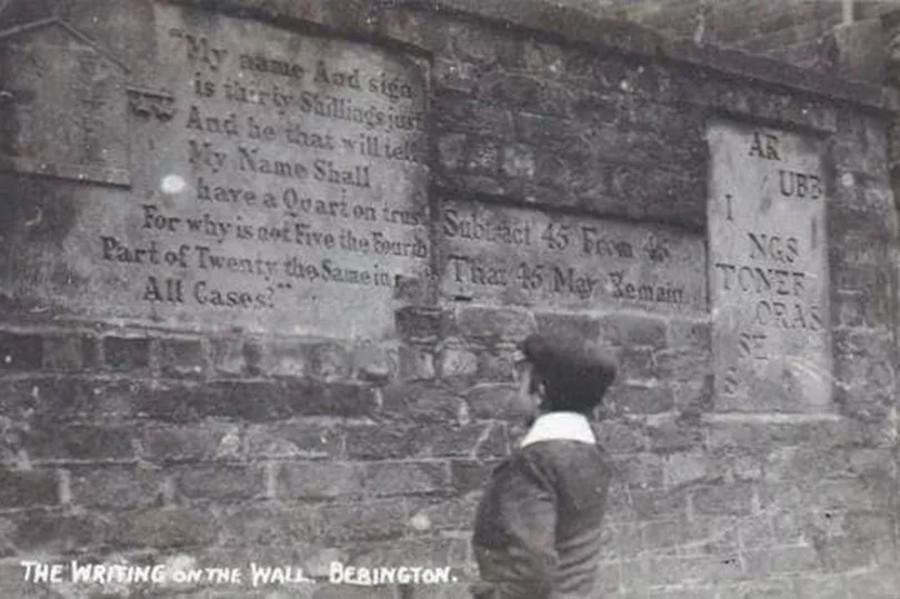

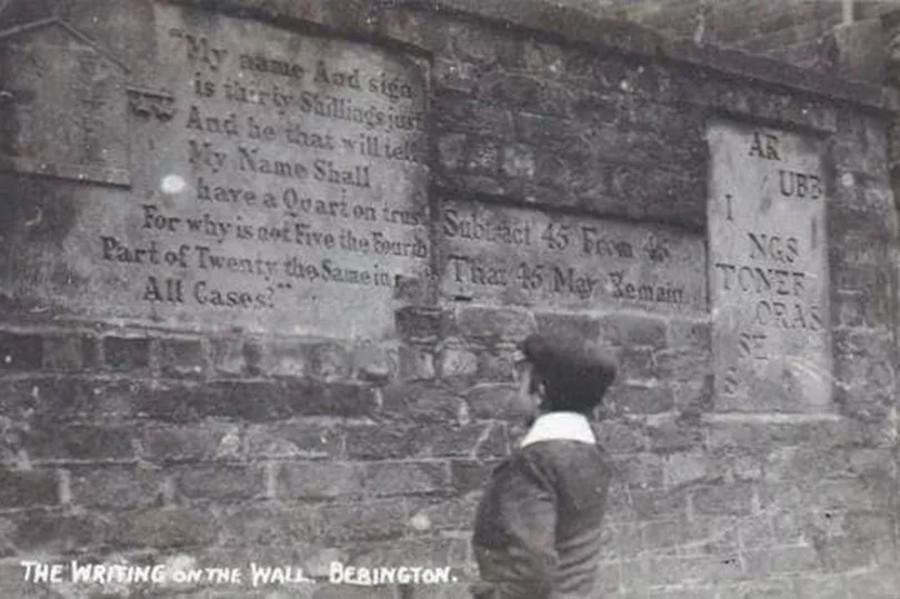

Visiting England’s Wirral Peninsula in 1853, Nathaniel Hawthorne came upon a queer battlemented house in the town of Bebington, “quite a novel symbol of decay and neglect,” “probably the whim of some half-crazy person.” “On the wall, close to the street, there were certain eccentric inscriptions cut into slabs of stone, but I could make no sense of them.”

The crazy person was resident Thomas Francis, and the inscriptions had apparently been commissioned to bemuse and entertain passersby. They offer three puzzles. The first presents the image of an inn, The Two Crowns, and the following riddle:

“My name And sign is thirty Shillings just, and he that will tell My Name Shall have a Quart on trust, for why is not Five the Fourth Part of Twenty the Same in All Cases?”

This was easier to guess at the time of its inscription. The landlord of the Two Crowns was Mark Noble, the old English coin known as the noble was worth 6 shillings and eightpence, the mark was worth 13 shillings and fourpence, and two crowns were worth 10 shillings. Together these values total 30 shillings.

The second puzzle is more straightforward: “Subtract 45 From 45 That 45 May Remain.” This seems to refer to the following mathematical curiosity:

987654321

- 123456789

-----------

864197532

Each of these figures comprises the digits 1 to 9, so all have the same digit sum: 45.

The last puzzle is the easiest:

AR

UBB

I

NGS

TONEF

ORAS

SE

S

Read this straight through and you get A RUBBING STONE FOR ASSES — possibly a comment by Francis on the loiterers who would gather outside his home.

The house was demolished in the 1960s, but the stones can be seen today in the foyer of the library at the Bebington civic center.