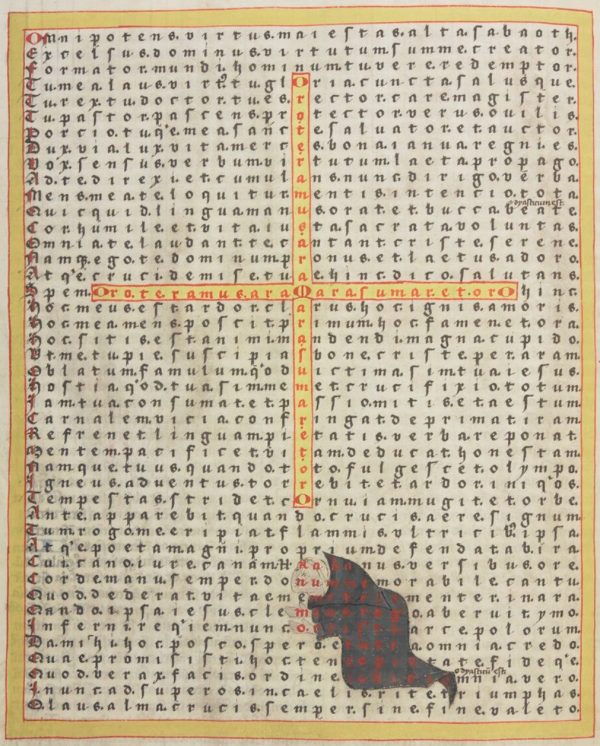

In 840 the Frankish Benedictine monk Rabanus Maurus composed 28 poems in which each line comprises the same number of letters. That’s impressive enough, but he also added painted images behind each poem that identify subsets of its letters that can be read on their own.

The final poem of the volume shows Rabanus Maurus himself kneeling in prayer at the foot of a cross whose text forms a palindrome: OROTE RAMUS ARAM ARA SUMAR ET ORO (I, Ramus, pray to you at the altar so that at the altar I may be taken up, I also pray). This text appears on both arms of the cross, so it can be read in any of four directions.

The form of the monk’s own body defines a second message: “Rabanum memet clemens rogo Christe tuere o pie judicio” (Christ, o pious and merciful in your judgment, keep me, Rabanus, I pray, safe).

And the letters in both of these painted sections also participate in the larger poem that fills the body of the page.

(From Laurence de Looze, The Letter and the Cosmos, 2016.)