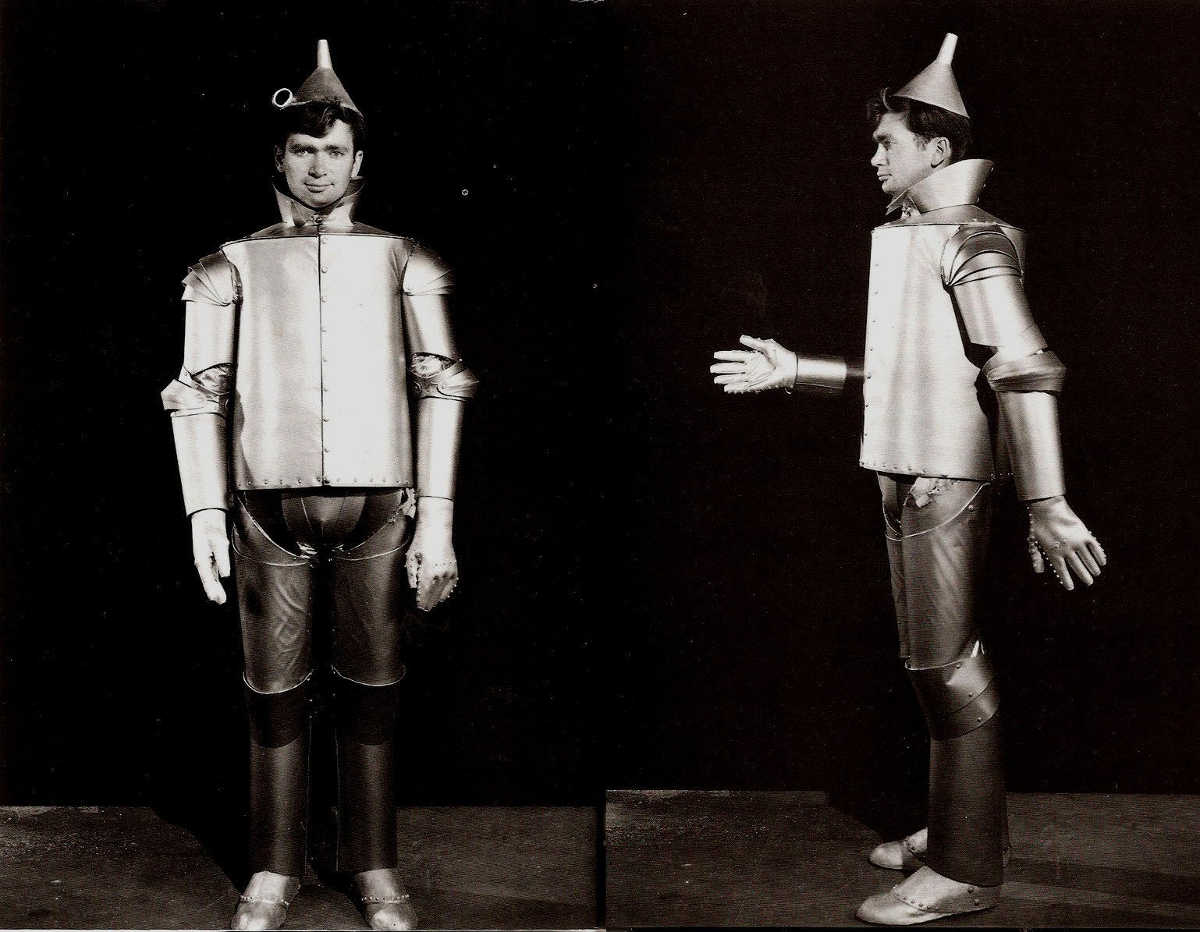

One last Wizard of Oz anecdote: Buddy Ebsen was originally cast as the Tin Man, but nine days into production he was in Good Samaritan Hospital with blue skin and labored breathing. He’d spent four weeks in rehearsal, where, after many makeup tests, they had powdered aluminum dust onto his face and head. “One night, after dinner, I took a breath and nothing happened. They got an ambulance and had me down to Good Samaritan for a couple of weeks. My lungs were coated with that aluminum dust they had been powdering on my face.” Apparently it had caused an allergic reaction.

After two weeks of waiting, producer Mervyn LeRoy replaced Ebsen with Jack Haley, who was not told what had happened, though the makeup was adapted to a paste. Haley wasn’t even asked if he wanted to play the part — 20th Century Fox simply loaned him to MGM. “The type of contract I had, I had to respond to their commands. I had no choice. I was under contract, and they could lend me to any studio. It was the most awful work, the most horrendous job in the world with those cumbersome uniforms and the hours of makeup, but I had no choice.”

(From Aljean Harmetz, The Making of The Wizard of Oz, 1977.)