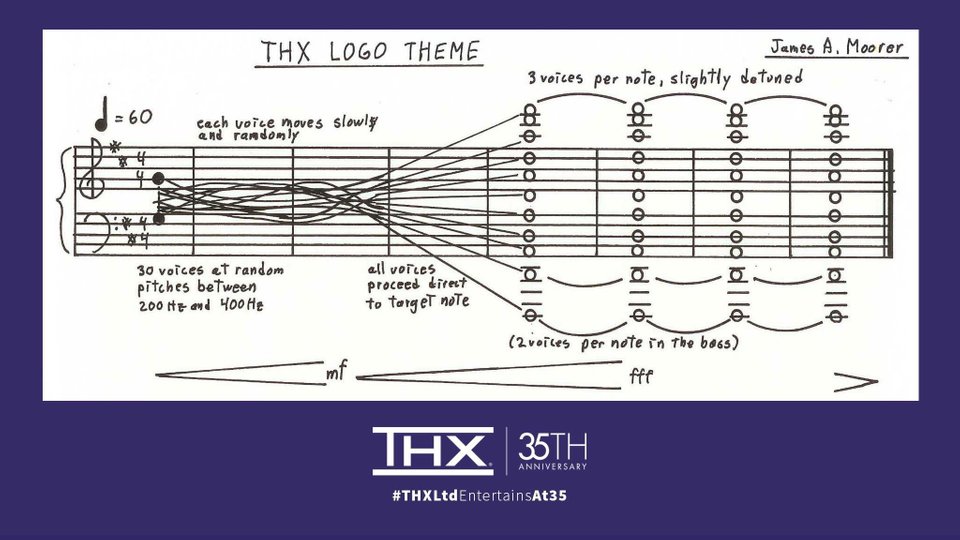

On its 35th anniversary, THX, the sound quality assurance company founded by George Lucas, released the original score of “Deep Note,” its audio trademark, which debuted at the premiere of Return of the Jedi in 1983 and is now familiar from countless films. Essentially it’s a stupendous D chord; the U.S. trademark registration reads:

The THX logo theme consists of 30 voices over seven measures, starting in a narrow range, 200 to 400 Hz, and slowly diverting to preselected pitches encompassing three octaves. The 30 voices begin at pitches between 200 Hz and 400 Hz and arrive at pre-selected pitches spanning three octaves by the fourth measure. The highest pitch is slightly detuned while there are double the number of voices of the lowest two pitches.

“I like to say that the THX sound is the most widely-recognized piece of computer-generated music in the world,” says James A. Moorer, who wrote it. “This may or may not be true, but it sounds cool.” And now that we have the score you can do this: