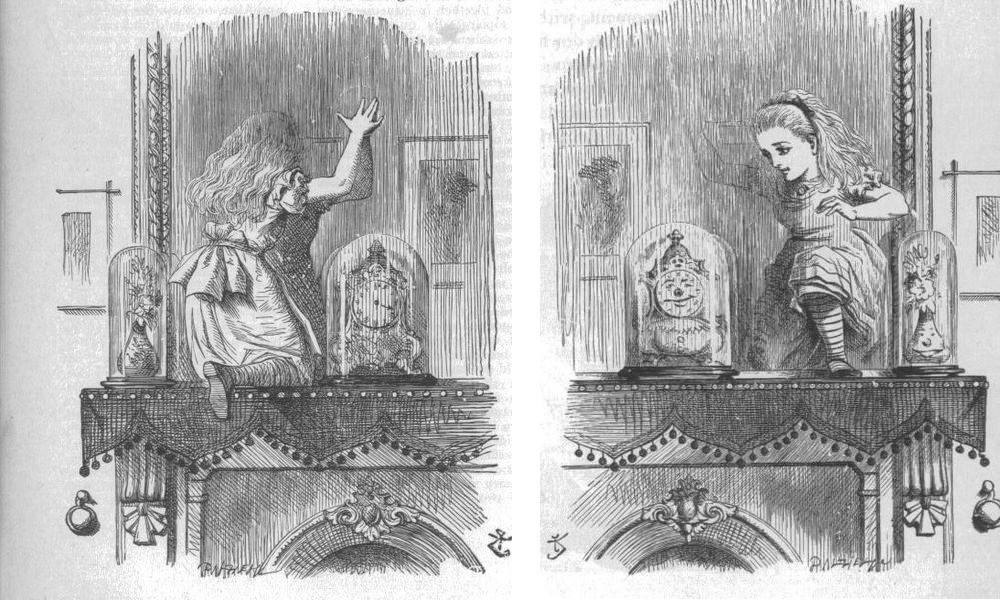

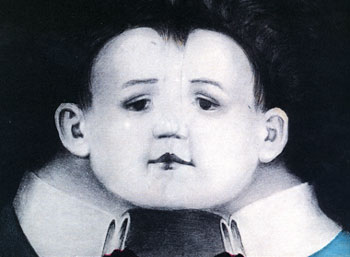

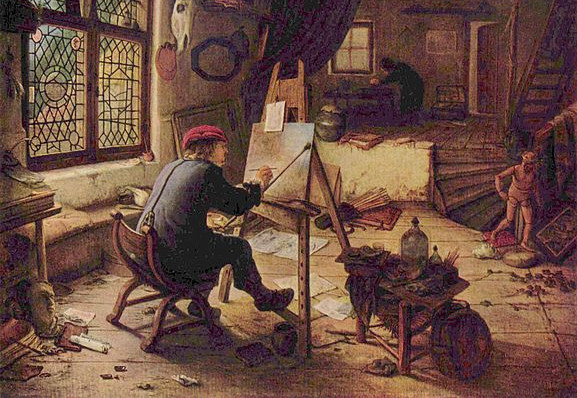

A poor artist is visited by a time traveler from the future. The traveler is an art critic who has seen the artist’s work and is convinced that he’s one of the greatest painters of his time. In looking at the artist’s current paintings, the critic realizes that the artist hasn’t yet reached the zenith of his ability. He gives him some reproductions of his later work and then returns to the future. The artist spends the rest of his life copying these reproductions onto canvas, securing his reputation.

What is the problem here? Kurt Gödel showed in 1949 that time travel might be physically possible, and there’s no contradiction involved in the critic arriving in the artist’s garret, giving him the reproductions, and later admiring the painter’s copies of them — that loop might simply exist in the fabric of time.

What’s missing is the source of the artistic creativity that produces the paintings. “No one doubts the aesthetic value of the artist’s paintings, nor the sense in which the critic’s reproductions reflect this value,” writes philospher Storrs McCall. “What is incomprehensible is: who or what creates the works that future generations value? Where is the artistic creativity to be found? Unlike the traditional ‘paradoxes of time travel’, this problem has no solution.”

(Storrs McCall, “An Insoluble Problem,” Analysis 70:4 [October 2010], 647-648.)