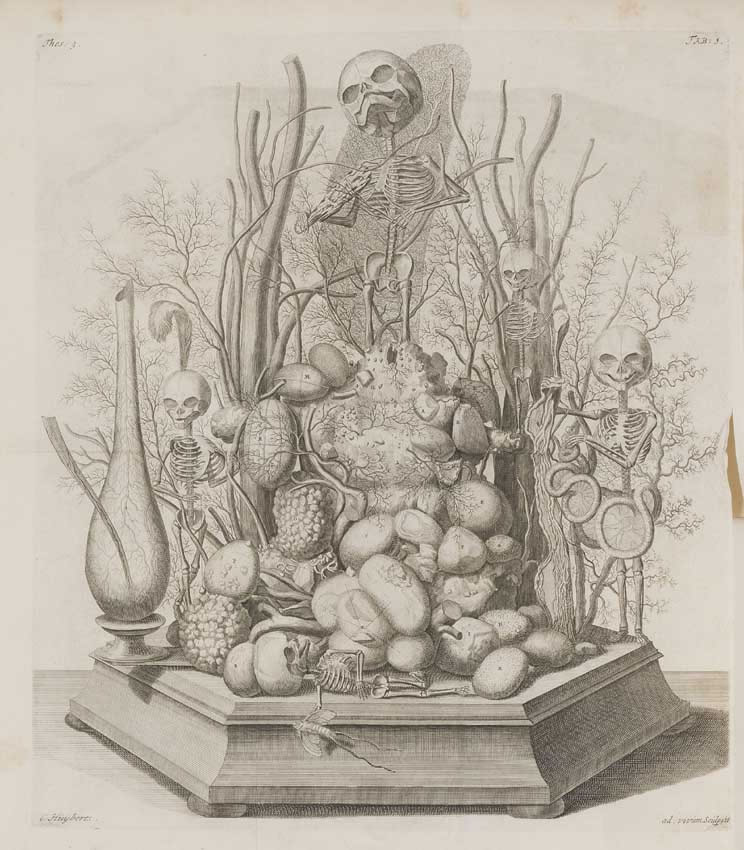

Dutch anatomist Frederik Ruysch had a curious sideline: He arranged fetal skeletons into allegorical dioramas on death and the transience of life. Set amid landscapes made of gallstones, kidney stones and preserved blood vessels, the skeletons are decorated with symbols of short life — one holds a mayfly, another weeps into a handkerchief made of brain meninges. Worms made of intestine wind through their rib cages. “Quotations and moral exhortations, emphasizing the brevity of life and the vanity of earthly riches, festooned the compositions,” notes Stephen Jay Gould in Finders, Keepers. “One fetal skeleton holding a string of pearls in its hand proclaims, ‘Why should I long for the things of this world?’ Another, playing a violin with a bow made of a dried artery, sings, ‘Ah fate, ah bitter fate.'”

Johannes Brandt, a Remonstrant teacher, wrote:

Oh, what are we? What remains of us when we are dead?

Behold, it is no living thing, but dry, bare bone instead.

Bladder stones you see in heaps, piled higher by the morrow:

Here one learns about life’s course through storms of pain and sorrow.

These wise lessons Ruysch presents with wit and erudition,

Amsterdam is fortunate to have this great physician.