From Lee Sallows:

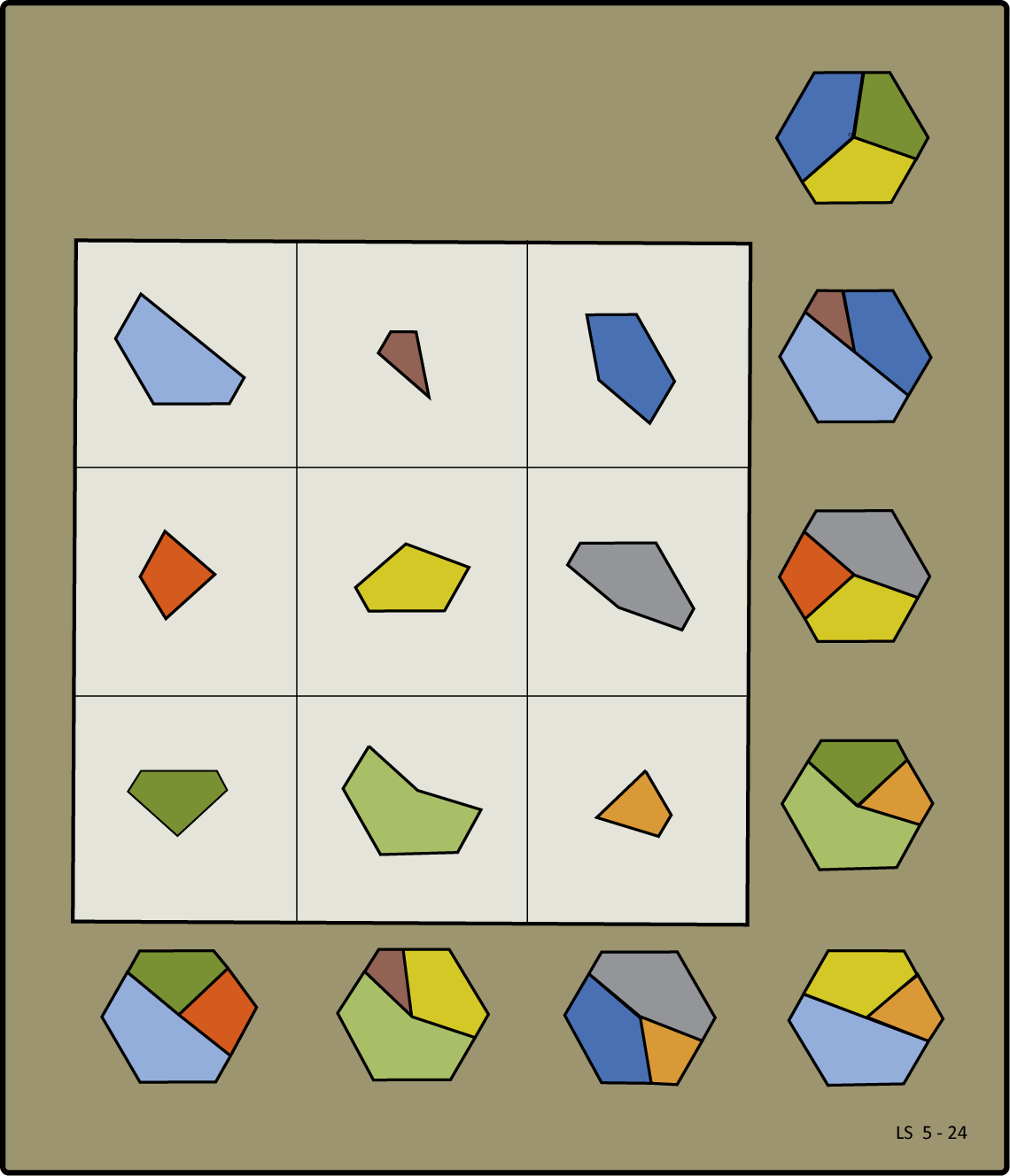

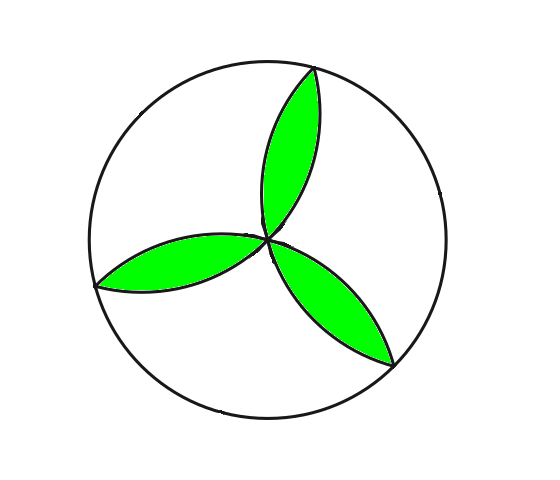

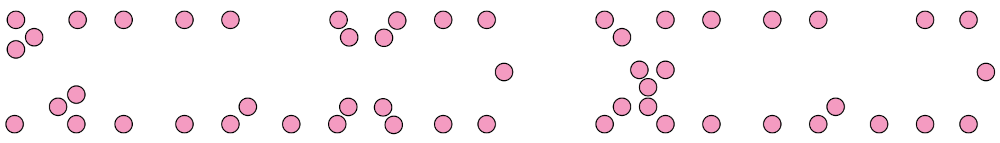

A feature common to many geomagic squares is that the set of shapes they employ reveal an atomic structure. That is, they are built up from repeated copies of a single unit shape. Examples of this are piece sets composed of polyominoes, the unit shape then being a (relatively small) square.

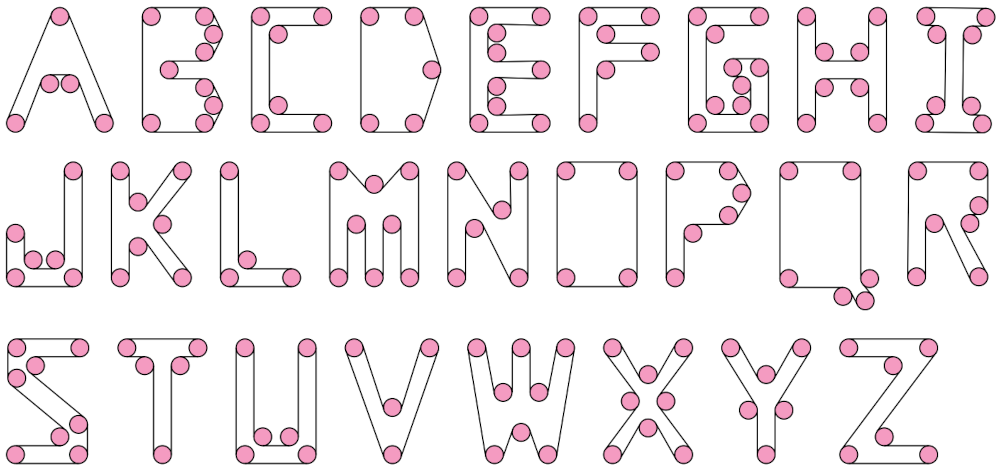

For the would-be geomagic square constructor, a key advantage of the atomic property is that the shapes concerned are each describable in terms of the positions of their constituent atoms. Or, to put it another way, they can be represented by a set of numbers. Hence, unlike non-atomic shapes, they are readily amenable to analysis and manipulation by computer.

Take, for example, an algorithm able to identify and list each of the different ways in which a given planar shape can be tiled by some specified set of smaller shapes. Such a program might be challenging to write, but provided the pieces concerned are composed of repeated units, implementation ought to be straightforward. But could the same be said in the case of non-atomic pieces? Without a set of numbers to describe piece shapes, how are they to be represented in a digital computer?

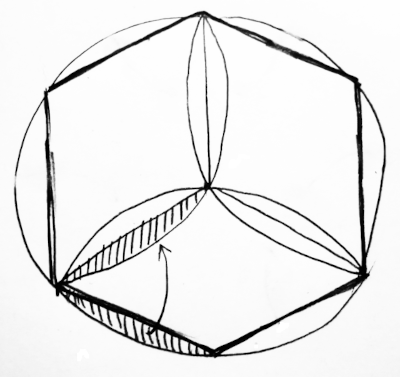

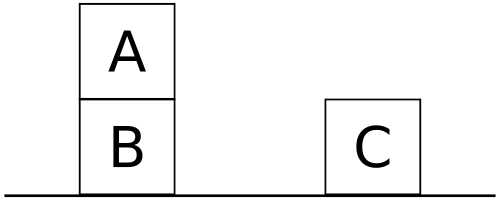

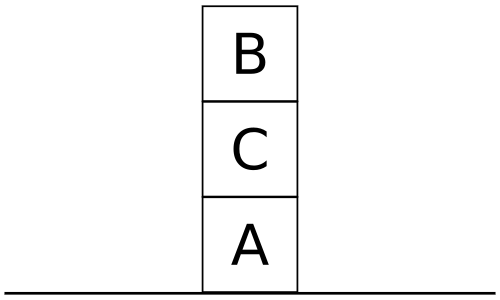

This is worth noting since, as inspection will show, the shapes employed in the square above are plainly non-atomic. In line with this I can confirm that the only computer program involved in deriving this solution was a vector graphics editor used to create the drawing seen above.

(Thanks, Lee.)