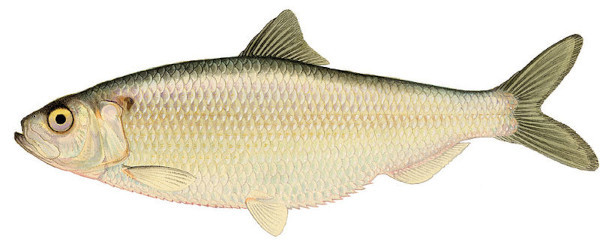

Early European colonists were staggered at the abundance of fish in the Chesapeake Bay. William Byrd II wrote in his natural history of Virginia:

Herring are not as large as the European ones, but better and more delicious. When they spawn, all streams and waters are completely filled with them, and one might believe, when he sees such terrible amounts of them, that there was as great a supply of herring as there is water. In a word, it is unbelievable, indeed, indescribable, as also incomprehensible, what quantity is found there. One must behold oneself.

More accounts here. “The abundance of oysters is incredible,” marveled Swiss explorer Francis Louis Michel in 1701. “There are whole banks of them so that the ships must avoid them. A sloop, which was to land us at Kingscreek, struck an oyster bed, where we had to wait about two hours for the tide.”