History

Down Under

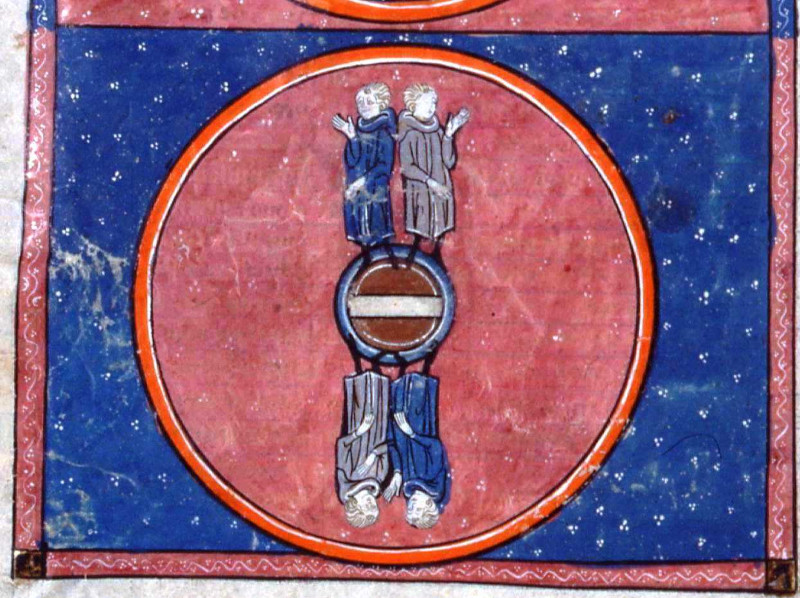

How is it with those who imagine that there are antipodes opposite to our footsteps? Do they say anything to the purpose? Or is there any one so senseless as to believe that there are men whose footsteps are higher than their heads? Or that the things which with us are in a recumbent position, with them hang in an inverted direction? That the crops and trees grow downwards? That the rains, and snow, and hail fall upwards to the earth? And does any one wonder that hanging gardens are mentioned among the seven wonders of the world, when philosophers make hanging fields, and seas, and cities, and mountains?

— Lactantius, Institutiones Divinae, 303

Tops

At the time of its completion under Hadrian, the Pantheon in Rome had the world’s largest unreinforced concrete dome.

It still does. It’s held that record for nearly 2,000 years.

Illumination

The Tyrians having been much weakened by long wars with the Persians, their slaves rose in a body, slew their masters and their children, took possession of their property, and married their wives. The slaves, having thus obtained everything, consulted about the choice of a king, and agreed that he who should first discern the sun rise should be king. One of them, being more merciful than the rest, had in the general massacre spared his master, Straton, and his son, whom he hid in a cave; and to his old master he now resorted for advice as to this competition.

Straton advised his slave that when others looked to the east he should look toward the west. Accordingly, when the rebel tribe had all assembled in the fields, and every man’s eyes were fixed upon the east, Straton’s slave, turning his back upon the rest, looked only westward. He was scoffed at by every one for his absurdity, but immediately he espied the sunbeams upon the high towers and chimneys in the city, and, announcing the discovery, claimed the crown as his reward.

— Charles Carroll Bombaugh, Gleanings From the Harvest-Fields of Literature, 1869

To the Life

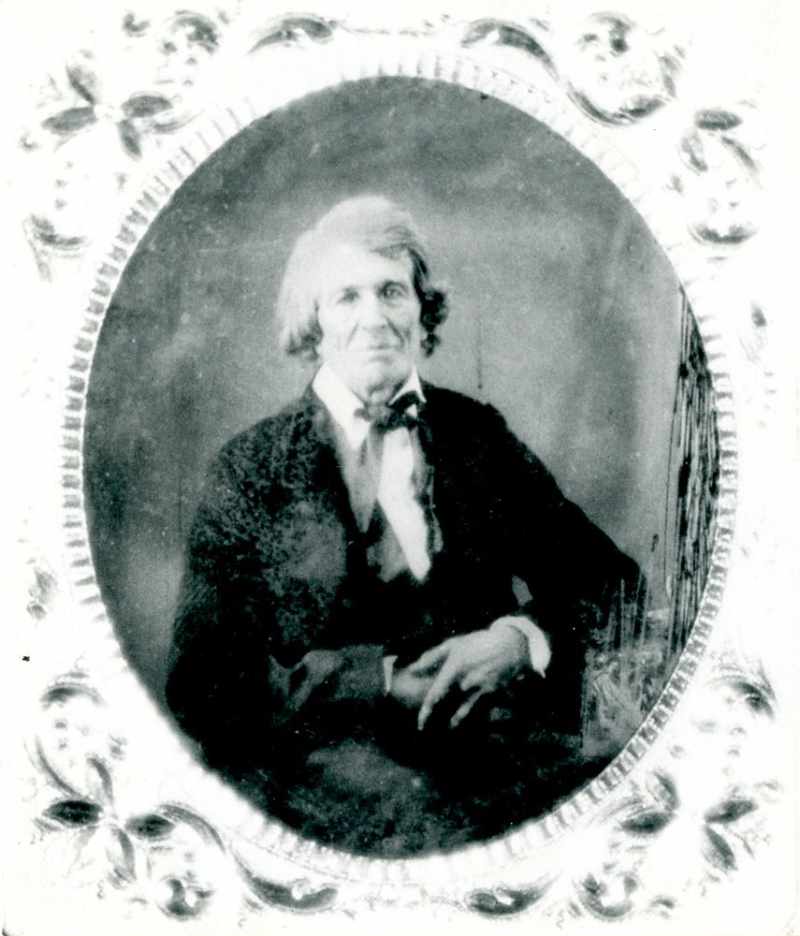

John Owen, one of the last veterans of the French and Indian War, lived to be 107 and posed for this photograph shortly before his death in 1843.

That makes him one of the earliest-born humans ever to be photographed. He was born in 1735.

Succinct

In November 1943, as they planned a summit meeting, FDR wired Churchill to suggest that Cairo might be too dangerous a location. Churchill responded:

SEE ST. JOHN, CHAPTER 14, VERSES 1 TO 4.

These verses read:

- Let not your heart be troubled: ye believe in God, believe also in me.

- In my Father’s house are many mansions; if it were not so, I would have told you, I go to prepare a place for you.

- And if I go and prepare a place for you, I will come again, and receive you unto myself; that where I am, there ye may be also.

- And whither I go ye know, and the way ye know.

They met in Cairo.

Time Out of Joint

In 1582, as the Catholic world prepared to adopt the new Gregorian calendar, German pamphleteers lampooned the strife that attended the change:

The old calendar must be the right one for the animals still use it. The stork flies away according to it, the bear comes out of his hole on the Candlemas day of the old calendar and not of the Pope’s, and the cattle stand up in their stalls to honor the birth of the Lord on the Christmas night of the old and not of the new calendar. They also recognize in this work diabolical wickedness. The Pope was afraid the last day would come too quickly. He has made his new calendar so that Christ will get confused and not know when to come for the last judgment, and the Pope will be able to continue his knavery still longer. May Gott him punish.

“Inanimate objects were not so stubborn.” An Italian walnut tree that had reliably put forth leaves, nuts, and blossoms on the night before Saint John’s day under the old regime dutifully adopted the new calendar and performed its feat on the correct day in 1583. A traveler wrote, “I have today sent a branch, broken off on Saint John’s day, to Herr von Dietrichstein, who no doubt will show it to the Kaiser.”

(Roscoe Lamont, “The Reform of the Julian Calendar,” Popular Astronomy 28:1 [January 1920], 18-32.)

Performance Review

The index to David Lloyd George’s 1938 War Memoirs sums up his feelings about Field Marshal Douglas Haig:

his refusal to face unpleasant facts

his limited vision

Germans accustomed to his heavy-footed movements

his stubborn mind transfixed on Somme

his misconceptions concerning morale of German army

obsessed with Passchendaele and optimistic as to military outlook

none of his essential conditions for success prevail at Passchendaele

misrepresents French attitude

his plans strongly condemned by Foch

misleads Cabinet about Italian Front

prefers to gamble his hopes on men’s lives than to admit an error

completely ignorant of state of ground at Passchendaele

fails to appreciate the value of tanks

not anxious for success on Italian Front

a mere name to men in the trenches

narrowness of his outlook

incapable of changing his plans

his judgement on general situation warped by his immediate interests

his fanciful estimates of man-power

jealous of Foch

does not expect big German attack in 1918

distributes his reserves very unwisely

his conduct towards Fifth Army not strictly honourable

his unwise staff appointments

his defeatist memorandum of 25/3/18

unfairly removes Gough from command of Fifth Army

his complaints as to lack of men unjustified

does not envisage Americans being of use in 1918

stubbornness

unreliability of his judgments

launches successful attack of 8/8/18 […] but fails to follow it up

his censorious criticism of his associates

his attempt to shirk blame for March, 1918, defeat

only took part in one battle during War

Also: “unequal to his task”, “industrious but uninspired”, “did not inspire his men”, “entirely dependent on others for essential information”, “the two documents that prove his incapacity”, “unselfish but self-centred”, “his inability to judge men”, “liked his associates to be silent and gentlemanly”, “his contempt for Foch”, “his intrigues against Lord French and Kitchener”, “his failure at Loos”, “his ingenuity in shifting blame to other shoulders than his own”, “his shabby treatment of Gough”, and “his conspiracy to destroy General Reserve”. He found in Haig’s diaries “a sustained egoism which is almost a disease.”

Oh

A garrulous barber asked the Macedonian king Archelaus, “How shall I cut your hair?”

He answered, “In silence.”

(From Plutarch.)

Queries

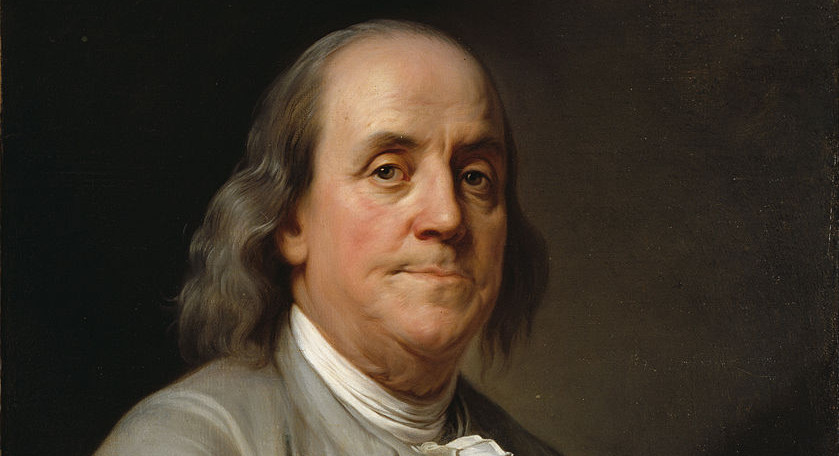

Questions put by Benjamin Franklin to his Junto, a club for mutual improvement that he founded in Philadelphia in 1727:

- How shall we judge of the goodness of a writing? Or what qualities should a writing have to be good and perfect in its kind? (His own answer: “It should be smooth, clear, and short.”)

- Can a man arrive at perfection in this life, as some believe; or is it impossible, as others believe?

- Wherein consists the happiness of a rational creature?

- What is wisdom? (“The knowledge of what will be best for us on all occasions, and the best ways of attaining it.”)

- Is any man wise at all times and in all things? (“No, but some are more frequently wise than others.”)

- Whether those meats and drinks are not the best that contain nothing in their natural taste, nor have anything added by art, so pleasing as to induce us to eat or drink when we are not thirsty or hungry, or after thirst and hunger are satisfied; water, for instance, for drink, and bread or the like for meat?

- Is there any difference between knowledge and prudence? If there is any, which of the two is most eligible?

- Is it justifiable to put private men to death, for the sake of public safety or tranquillity, who have committed no crime? As, in the case of the plague, to stop infection; or as in the case of the Welshmen here executed?

- If the sovereign power attempts to deprive a subject of his right (or, which is the same thing, of what he thinks his right), is it justifiable in him to resist, if he is able?

- Which is best: to make a friend of a wise and good man that is poor or of a rich man that is neither wise nor good?

- Does it not, in a general way, require great study and intense application for a poor man to become rich and powerful, if he would do it without the forfeiture of honesty?

- Does it not require as much pains, study, and application to become truly wise and strictly virtuous as to become rich?

- Whence comes the dew that stands on the outside of a tankard that has cold water in it in the summer time?

From Carl Van Doren’s biography. “New members had to stand up with their hands on their breasts and say they loved mankind in general and truth for truth’s sake. … In time the Junto had so many applications for membership it was at a loss to know how to limit itself to the twelve originally planned.”