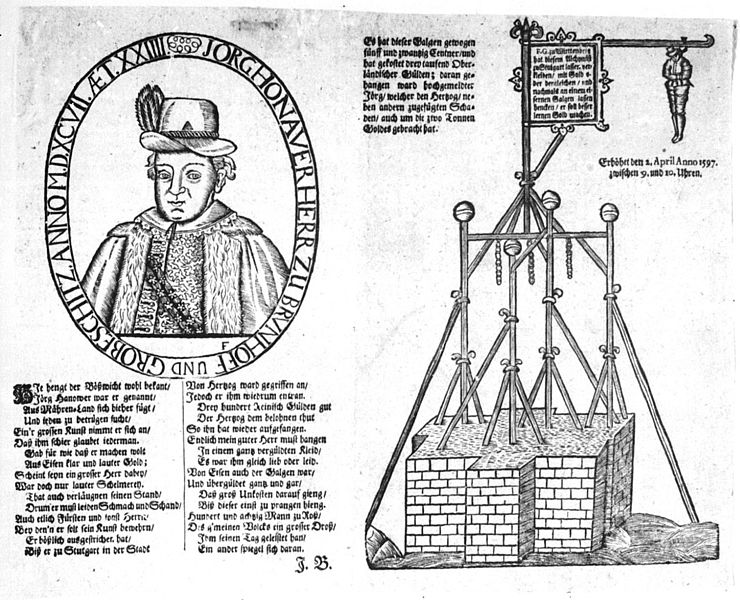

Ancient Athenians would sometimes encounter a remarkable sculpture on roads and in public places: The bearded head of the god Hermes set on a squared pillar of stone, with male genitals carved at the appropriate height. Hermes had been a phallic god before becoming a guardian of merchants and travelers, and so was associated with fertility, luck, roads, and borders. The hermae served as a form of protection from evil and were sometimes anointed with oil or bedecked with garlands.

Plato writes that “figures of Hermes” were set up “along the roads in the midst of the city and every district town” “with the design of educating those of the countryside,” sometimes by bearing edifying inscriptions. The sculptures did not always depict Hermes — this one, from the Athenian Agora, honors Demosthenes. The practice spread eventually to Rome, where the figures were known as mercuriae.

(Peter Keegan, Graffiti in Antiquity, 2014.)