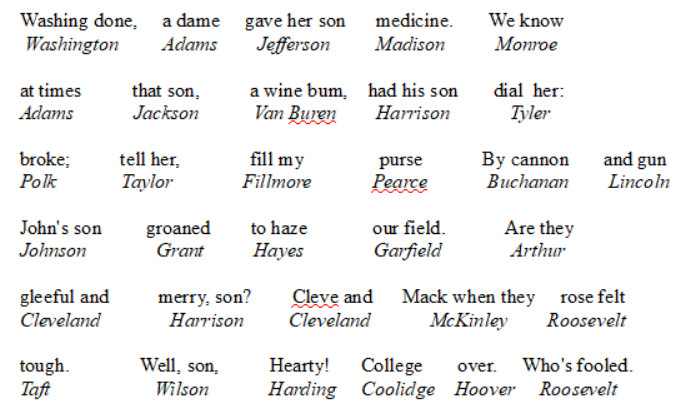

A phonetic mnemonic for the first 32 U.S. presidents, by Edwin C. Silvey:

I don’t know where this first appeared, but every source I can find faithfully credits the composer.

A phonetic mnemonic for the first 32 U.S. presidents, by Edwin C. Silvey:

I don’t know where this first appeared, but every source I can find faithfully credits the composer.

I take delight in history, even its most prosaic details, because they become poetical as they recede into the past. The poetry of history lies in the quasi-miraculous fact that once, on this earth, once, on this familiar spot of ground, walked other men and women, as actual as we are to-day, thinking their own thoughts, swayed by their own passions, but now all gone, one generation vanishing after another, gone as utterly as we ourselves shall shortly be gone like a ghost at cock-crow. This is the most familiar and certain fact about life, but it is also the most poetical, and the knowledge of it has never ceased to entrance me, and to throw a halo of poetry round the dustiest record that Dryasdust can bring to light.

— G.M. Trevelyan, Autobiography and Other Essays, 1949

In 1999, archaeologists made a stunning find near the summit of a stratovolcano on the Argentina–Chile border. Three Inca children, sacrificed in a religious ritual 500 years earlier, had been preserved immaculately in the small chamber in which they had been left to die. Due to the dryness and low temperature of the mountainside, the bodies had frozen before they could dehydrate, making them “the best-preserved Inca mummies ever found.” Even the hairs on their arms were intact; one of the hearts still contained frozen blood.

Known as the Children of Llullaillaco, they’re on display today at the Museum of High Altitude Archaeology in Salta.

crastin

n. the day after, the morrow

festinate

adj. hurried

hammajang

adj. in a disorderly or chaotic state

disceptation

n. disputation, debate, discussion

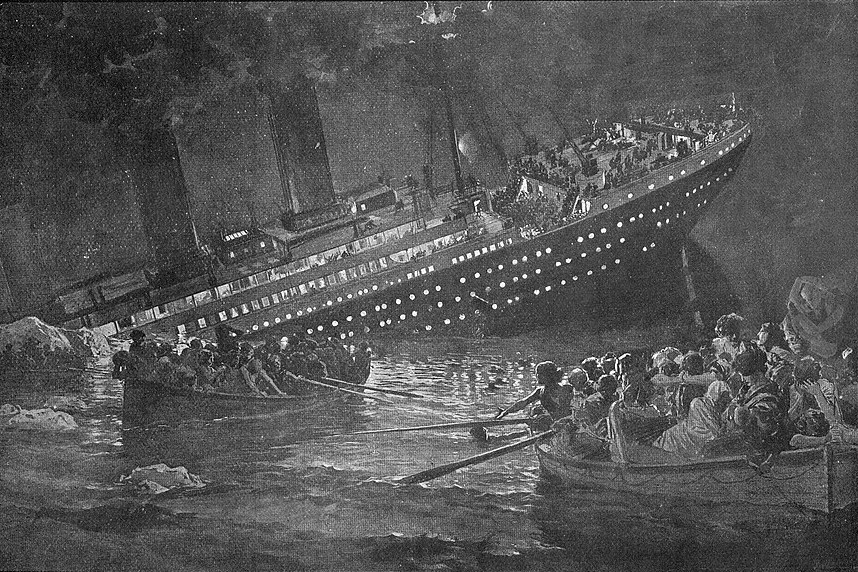

What time did various incidents happen? Everyone agrees that the Titanic hit the iceberg at 11:40 p.m. and sank at 2:20 a.m. — but there’s disagreement on nearly everything that happened in between. … There was simply too much pressure. Mrs. Louis M. Ogden, passenger on the Carpathia, offers a good example. At one point, while helping some survivors get settled, she paused long enough to ask her husband the time. Mr. Ogden’s watch had stopped, but he guessed it was 4:30 p.m. Actually, it was only 9:30 in the morning. They were both so engrossed, they had lost all track of time.

— Walter Lord, A Night to Remember, 1955

Sydney Smith suggested this inscription for William Pitt’s statue in Hanover Square:

To the Right Honourable William Pitt

Whose errors in foreign policy

And lavish expenditure of our Resources at home

Have laid the foundation of National Bankruptcy

And scattered the seeds of Revolution,

This Monument was erected

By many weak men, who mistook his eloquence for wisdom

And his insolence for magnanimity,

By many unworthy men whom he had ennobled,

And by many base men, whom he had enriched at the Public Expense.

But for Englishmen

This Statue raised from such motives

Has not been erected in vain.

They learn from it those dreadful abuses

Which exist under the mockery

Of a free Representation,

And feel the deep necessity

Of a great and efficient Reform.

“He was one of the most luminous, eloquent blunderers with which any people was ever afflicted,” Smith wrote. “God send us a stammerer; a tongueless man.”

During the Black Death, Florentine chronicler Giovanni Villani wrote, “The priest who confessed the sick and those who nursed them so generally caught the infection that the victims were abandoned and deprived confession, sacrament, medicine, and nursing … And many lands and cities were made desolate. And this plague lasted till ________.”

He left the blank so that he could record the date of the plague’s end, but then he himself succumbed, dying in 1348.

Another and still more amusing instance of self-revelation may be found in a manuscript familiar to many who have visited the Bodleian Library at Oxford. There, among other precious treasures, is a collection of notes scribbled by Charles II. to Clarendon, and by Clarendon to Charles II., to beguile the tedium of Council. They look, for all the world, like the notes which school-girls are wont to scribble to one another, to beguile the tedium of study. On one page, Charles in a little careless hand, not unlike a school-girl’s, writes that he wants to go to Tunbridge, to see his sister. Clarendon in larger, firmer characters writes back that there is no reason why he should not, if he can return in a few days, and adds tentatively, ‘I suppose you will go with a light train.’ Charles, as though glowing with conscious rectitude, responds, ‘I intend to take nothing but my night-bag.’ Clarendon, who knows his master’s luxurious habits, is startled out of all propriety. ‘Gods!’ he writes: ‘you will not go without forty or fifty horse.’ Then Charles, who seems to have been waiting for this point in the dialogue, tranquilly replies in one straggling line at the bottom of the page. ‘I count that part of my night-bag.’

— Agnes Repplier, Essays in Idleness, 1893

Henry George Liddell and Robert Scott’s Intermediate Greek-English Lexicon of 1851 contains a sobering entry:

ραφανιδοω: to thrust a radish up the fundament, a punishment of adulterers in Athens

In recalling this to friends at Christmas in 1972, historian John Julius Norwich wrote, “I’m sure it must once have been familiar to every schoolboy, and now that the classics are less popular than they used to be I should hate it to be forgotten.”

Freezing in the Canadian arctic in 1821, John Franklin noted some telling effects of fatigue in his companions:

I observed, that in proportion as our strength decayed, our minds exhibited symptoms of weakness, evinced by a kind of unreasonable pettishness with each other. Each of us thought the other weaker in intellect than himself, and more in need of advice and assistance. So trifling a circumstance as a change of place, recommended by one as being warmer and more comfortable, and refused by the other from a dread of motion, frequently called forth fretful expressions, which were no sooner uttered than atoned for, to be repeated, perhaps, in the course of a few minutes. The same thing often occurred when we endeavoured to assist each other in carrying wood to the fire; none of us were willing to receive assistance, although the task was disproportioned to our strength.

From Narrative of a Journey to the Shores of the Polar Sea, in the Years 1819-20-21-22, 1823.

One of the most beautiful and moving of the bird-songs heard throughout the country which [French merchant Nicolas] Denys governed [in 17th-century Acadia], is that of the Veery, or Wilson’s Thrush. The Maliseet Indians of the Saint John River, as Mr. Tappan Adney has recently told us, say this bird is calling Ta-né-li-ain′, Ni-kó-la Dĕn′-i Dĕn′-i?, that is, ‘Where are you going, Nicolas Denys?’ and Mr. Adney thinks this an actual echo from the days of our author.

— From William Francis Ganong’s 1908 introduction to Denys’ Description and Natural History of the Coasts of North America, 1672