There’s an interesting detail in Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait of 1434. The painting depicts Italian merchant Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini and his wife in their home in Bruges. In the background is a convex mirror over which is inscribed the legend “Johannes de eyck fuit hic 1434” (“Jan van Eyck was here 1434”). And curiously, reflected in the mirror, where we’d expect to see the painter and his easel, are two figures:

In 1934 art historian Erwin Panofsky offered a unique explanation for this: The painting is an “artistic marriage certificate.” Neither Arnolfini nor his new wife had any relatives at Bruges at the time of their marriage, and the custom at the time was to record two witnesses to the wedding. “So that we can understand the original idea of a picture which was a memorial portrait and a document at the same time, and in which a well-known gentleman-painter signed his name both as artist and as witness.”

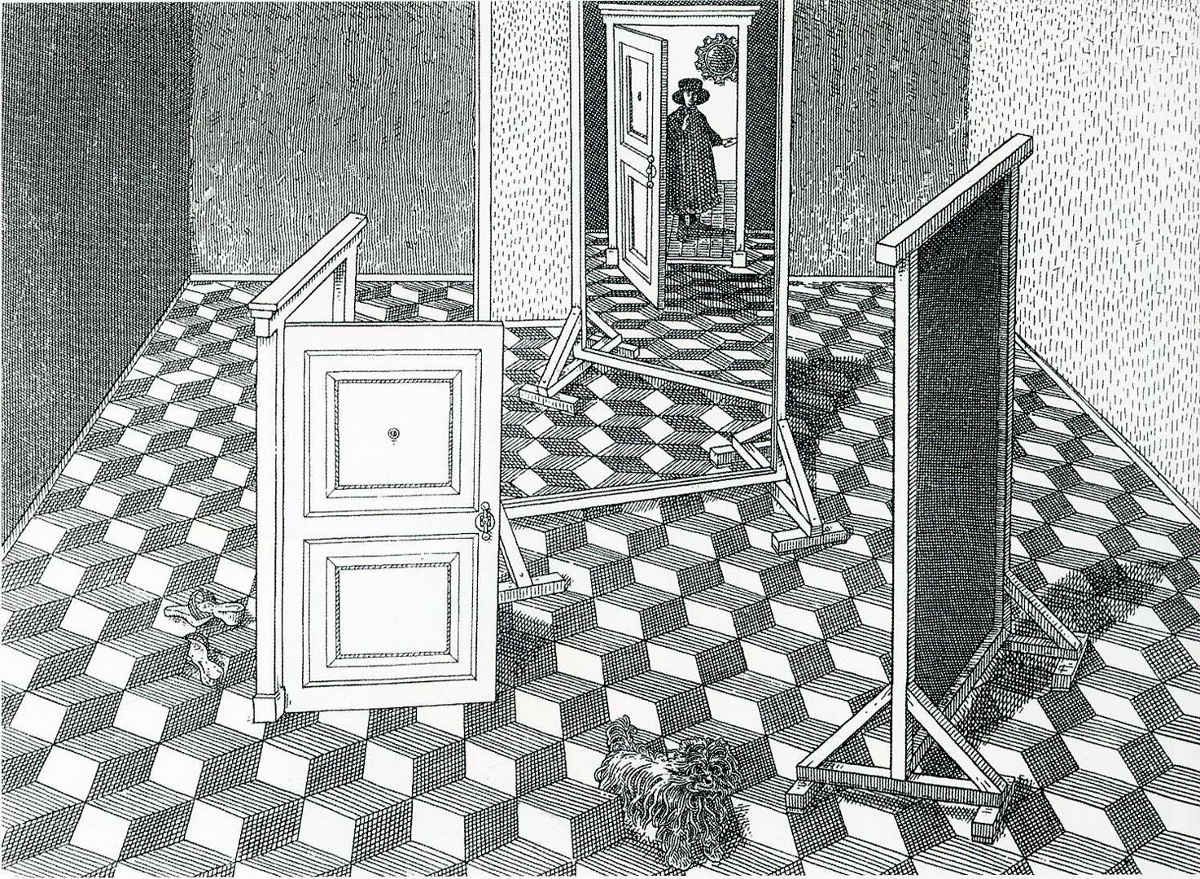

Amused by the reflection, Hungarian graphic designer István Orosz set up his own arrangement in his 1997 etching Johannes de Eyck fuit hic, below. “Here I attempt to show the world behind the door with the help of two mirrors.”

For a thousand bucks you can buy your own Van Eyck mirror and investigate for yourself.

(Erwin Panofsky, “Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait,” Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 64:372 [March 1934], 117-119.)