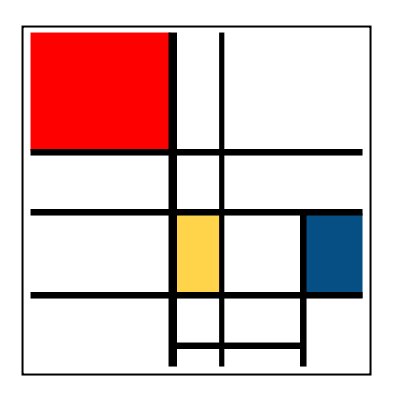

PIET MONDRIAN is an anagram of I PAINT MODERN.

PIET MONDRIAN is an anagram of I PAINT MODERN.

Before conductors used batons, they kept time by banging a long staff against the floor. In January 1687, Jean-Baptiste Lully was conducting a Te Deum in this way when he struck his toe. The wound turned gangrenous, the gangrene spread — and he died.

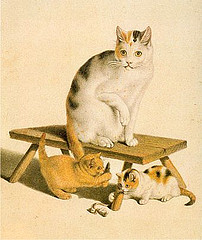

Born in Bern in 1768, the autistic Gottfried Mind could barely write his name, but on seeing a cat in a painting by his drawing-master, he immediately said, “That is no cat!” The master asked whether he thought he could do better, and Mind produced a drawing so good that the master copied it.

Thereafter Mind worked surrounded by cats, painting them with a remarkable eye for their individual character and occasionally carving them from chestnuts for sport. In the work of other artists it’s said that he liked nothing but the lions of Rubens, Rembrandt, and Paulus Potter, and he looked down even on celebrated cats by Cornelius Vischer and Wenzel Hollar.

“First and last,” said Goethe, “what is demanded of genius is love of truth.”

Picasso’s full name was Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Clito Ruiz y Picasso.

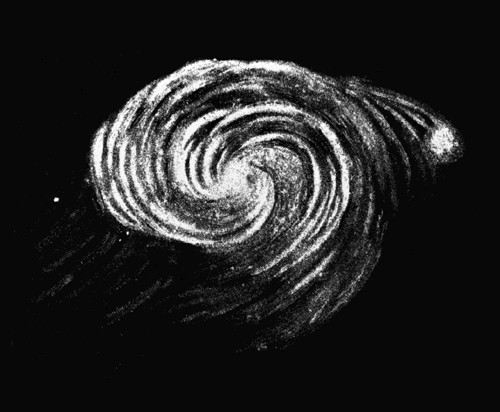

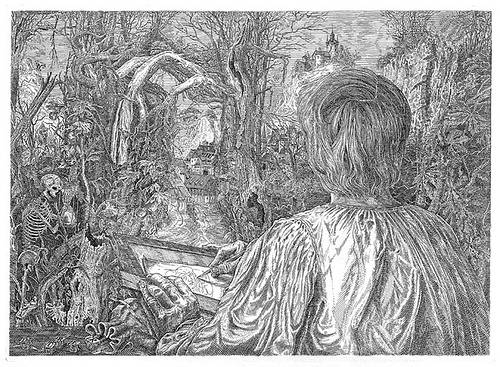

Etching by Hungarian artist István Orosz.

Oscar Wilde said, “Life imitates art far more than art imitates life.”

“See what will happen if you don’t stop biting your fingernails?” — Will Rogers, to his niece on seeing the Venus de Milo

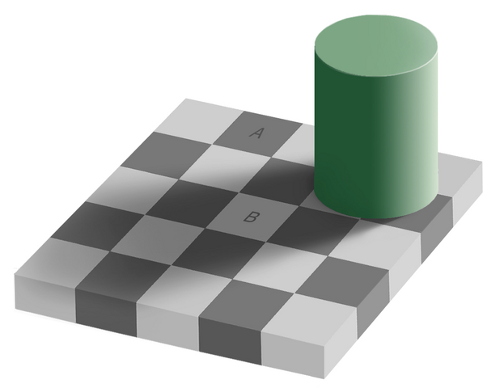

An optical illusion. Squares A and B are the same color.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo‘s caricature of Rudolf II’s historiographer and librarian, Wolfgang Lazio (1514-1565) — a collector of coins and a lover of books.

“All Is Vanity” (1892), by the American illustrator C. Allan Gilbert.

Back up to get the full effect.

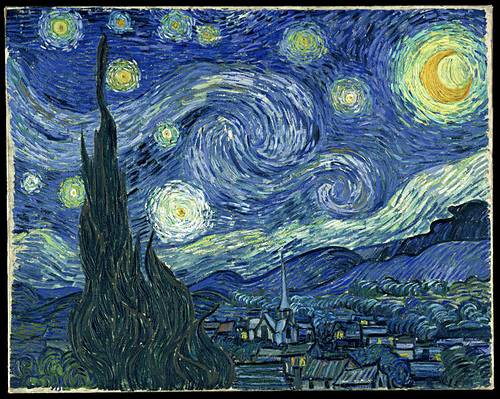

Irish astronomer William Parsons might have been surprised to see van Gogh’s The Starry Night appear in 1889.

He had drawn this sketch of the Whirlpool Galaxy 44 years earlier: