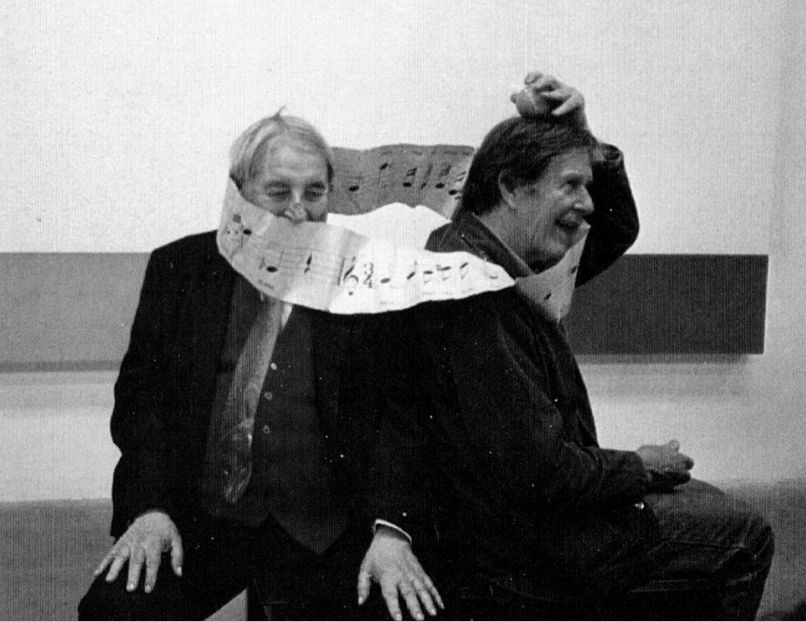

The Hurwitz Singularity, an anamorphic sculpture by artist Jonty Hurwitz, began with a scan of the artist’s own head.

“I wanted to capture my physical being in as much detail as technology allowed,” he writes. “It felt appropriate to be able to analyse myself at the highest resolution that modern science could record spacetime.”

“This sculpture evolved when I was deep in Freudian Therapy. Four days a week on the sofa blazing new trails from the road that Sigmund Freud first mapped. To my analyst I dedicate this piece. Dr Sanchez Bernal this is the Hurwitz Singularity!”

There’s more at the artist’s website.