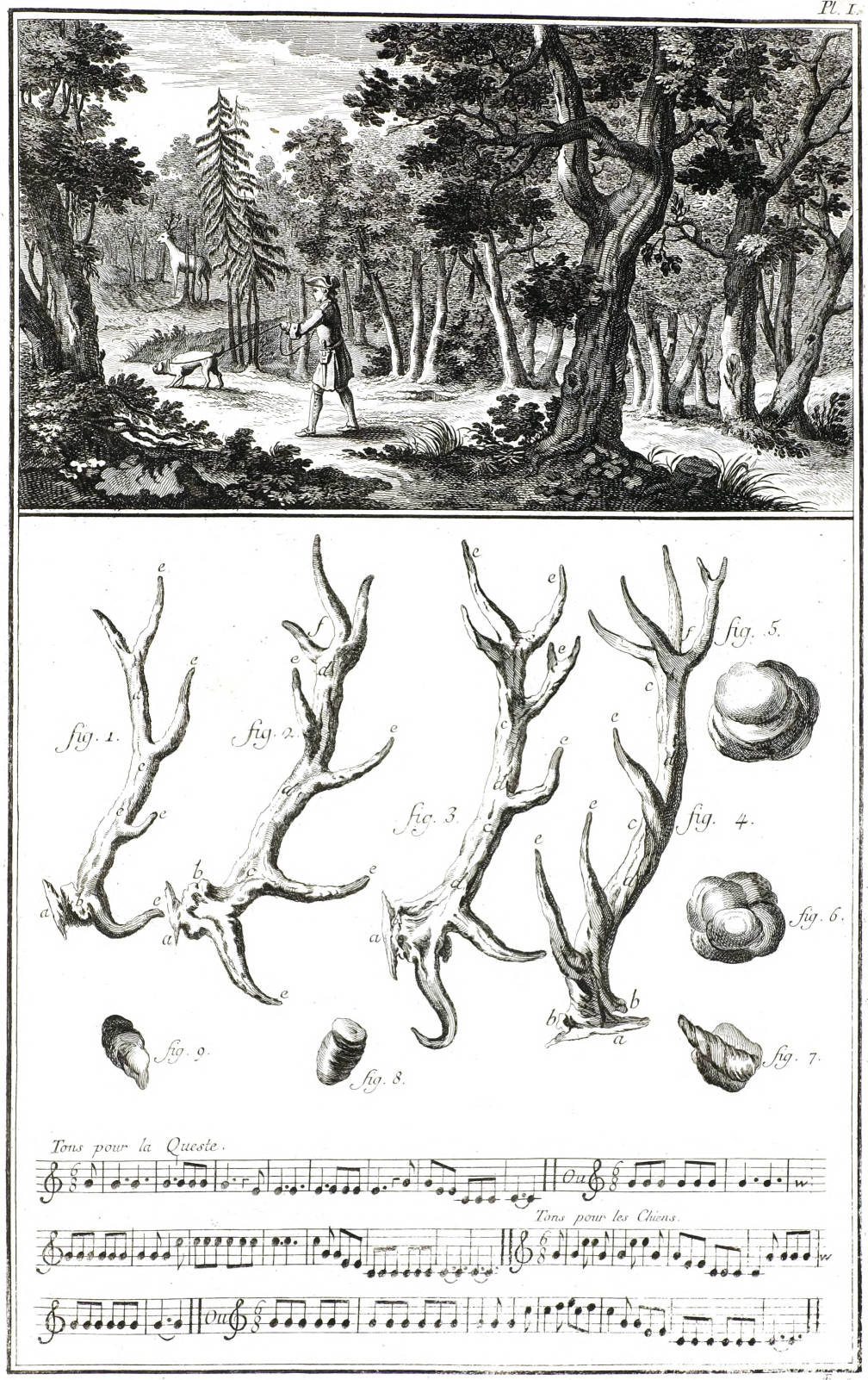

I don’t know why I find this so striking: It’s a diagram that accompanies the article on deer hunting in Denis Diderot’s Encyclopédie. Rather than presenting a single image with a caption, it combines a vignette of a deer hunt with an illustration of the antlers and piles of dung that are dropped by stags of different ages, together with a musical score showing the notes sounded by the hunting party at different stages of the pursuit.

“Taken as a whole the hunting plates offer few clues for reading their complex hybrid of imagery and notations as an ensemble,” write John Bender and Michael Marrinan in The Culture of the Diagram (2010). Perhaps as a result, the encyclopedia article requires nearly 10 pages.

“The Encyclopedia’s treatment of stag hunting is extraordinary for mobilizing a full range of written language, abstract and arbitrary notations, indexical icons, and pictorial tableaux in an attempt to diagram the highly ritualized, courtly craft of tracking animals under the Ancien Régime.”

Diderot provided similarly remarkable diagrams for “hunting at force,” the kill, boar hunting, and wolf hunting.