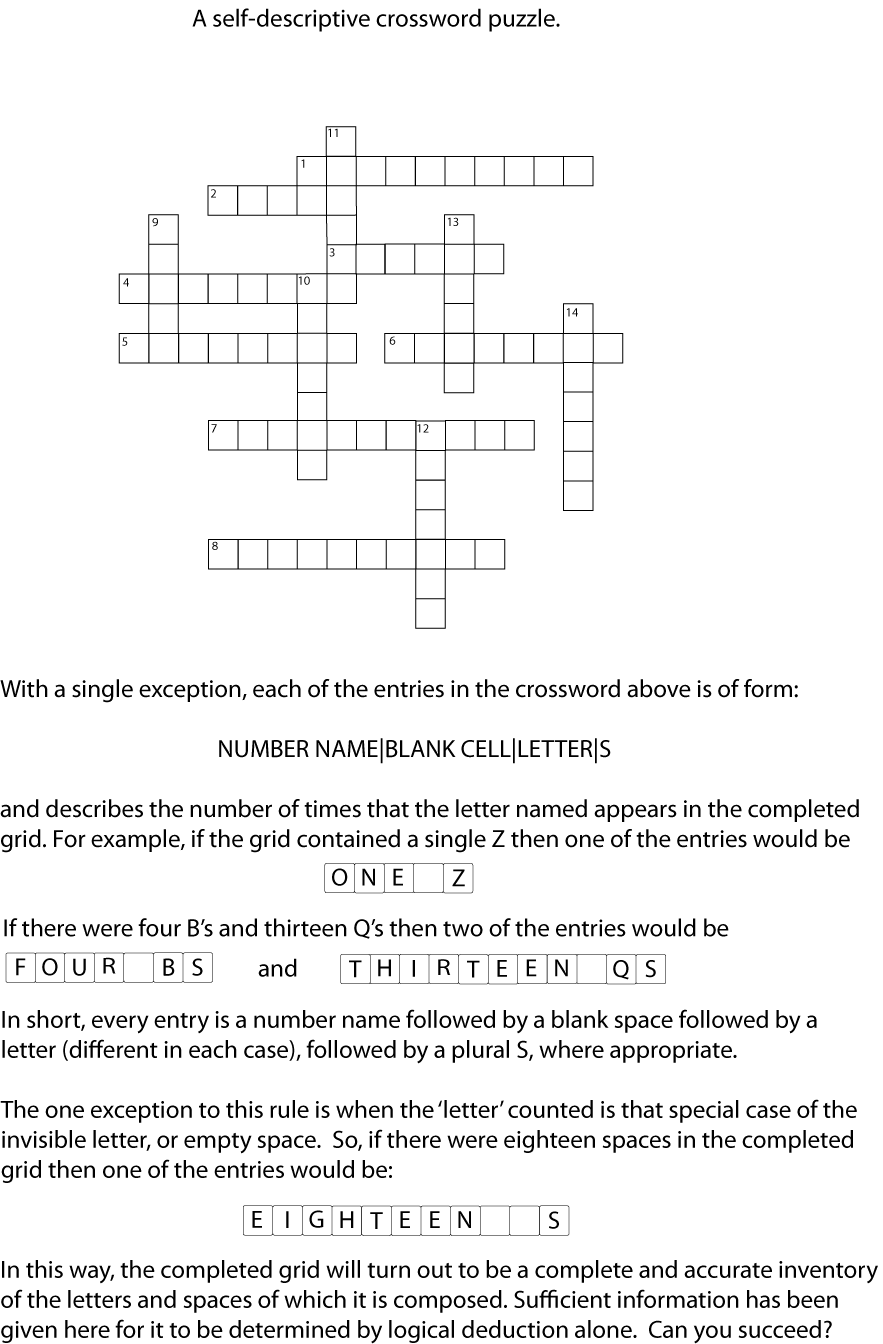

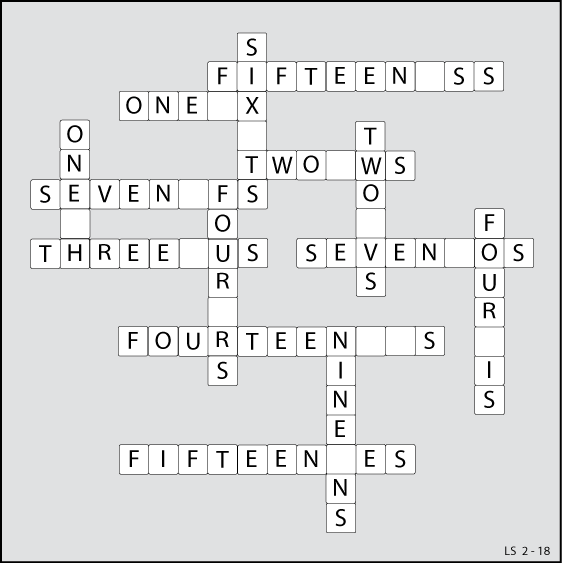

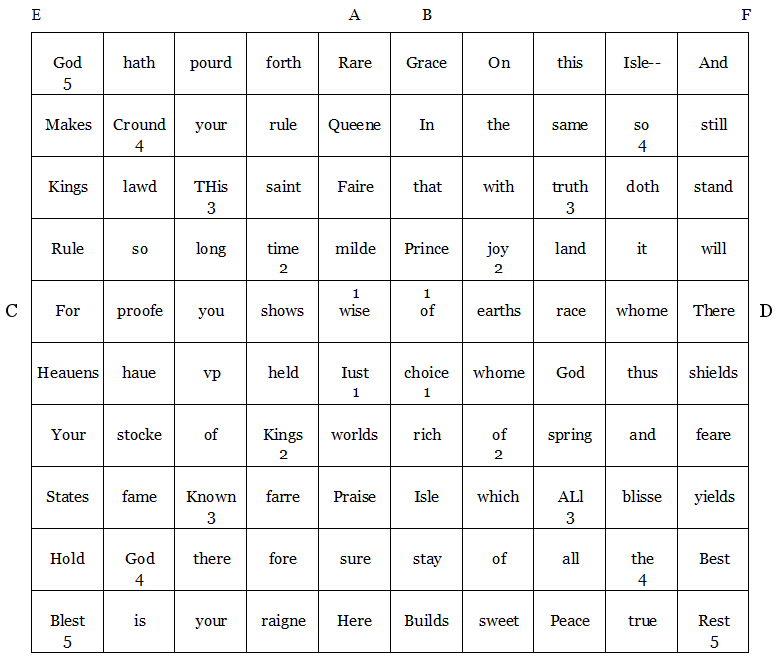

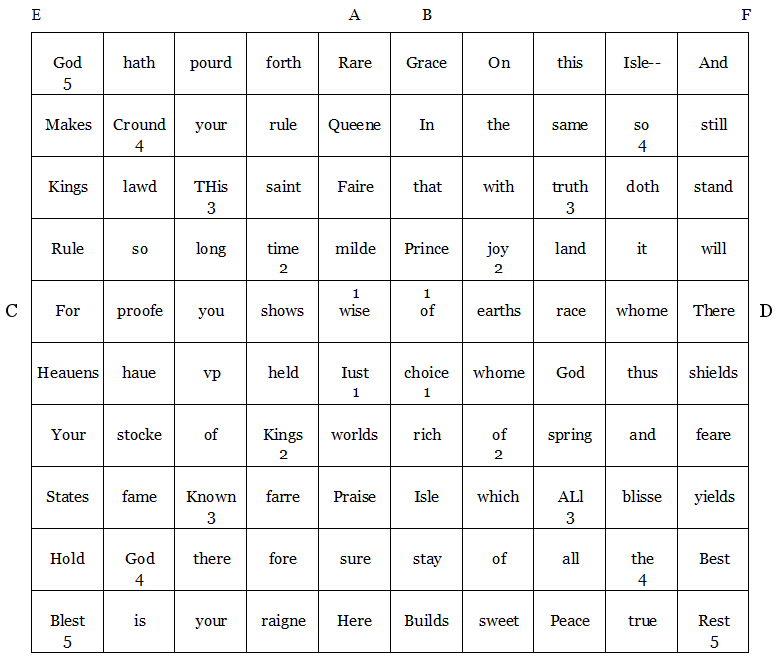

Princeton scholar Thomas P. Roche Jr. calls this “an astounding piece of ingenuity,” one of “the most elaborately numerological poems I have found in the Renaissance.” Poet Henry Lok created it in 1597, in honor of Elizabeth I. It can be read as a conventional 10-line poem, but there are fully eight other ways to read it:

“1. A Saint George’s crosse [+] of two collumbs, in discription of her Maiestie, beginning at A, and B, in the middle to be read downward, and crossing at C and D to be read either singly or double.”

Rare Queen, fair, mild, wise

Shows you proof

For heavens have upheld

Just world’s praise sure.

Here Grace in that Prince

Of earth’s race, who

There shields thus God

Whom choice (rich Isle, stay!) builds.

“2. A S[aint] Andrew’s crosse [X], beginning at E and read thwartwaies, and ending with F, containing the description of our happie age, by her highnesse.”

God crowned this time, wise choice of all the Rest,

And so truth, joy of just kings’ known, God blest.

“3. Two Pillars in the right and left side of the square, in verse reaching from E and F perpenddicularly, containing the sum of the whole, the latter columbe hauing the words placed counterchangeably to rime to the whole square.”

God makes kings rule for heauens; your state hold blest

And still stand will their shields; fear yields best rest.

“4. The first and last two verses or the third and fourth, with seuenth and eighth, are sense in them selues, containing also sense of the whole.”

“5. The whole square of 100, containing in it self fiue squares, the angles of each of them are sense particularly, and vnited depend each on other, beginning at the center.”

1 Just, wise of choice

2 Joy of kings’ time

3 This truth all known

4 So crowned the God

5 Blessed God and rest.

“6. The out-angles are to be read 8 seuerall waies in sense and verse.”

“7. The eight words placed also in the ends of the St. George’s crosse, are sense and verse, alluding to the whole crosse.”

Rare grace here builds

There shields for heaven.

Rare Grace there shields

For heaven here builds.

“8. The two third words in the bend dexeter of the St. Andrew’s crosse, being the middle from the angles to the center, haue in their first letters T. and A. for the Author, and H.L. in their second, for his name, which to be true, the words of the angles in that square confirme.”

THis ALl

T[he]H[enry]is A[uthor]L[ok]l

“9. The direction to her Maiestie in prose aboue, containeth onely of numerall letters, the yeare and day of the composition, as thus, DD. C. LL. LL. LL. LL. VV. VV. VV. IIIIIIIIIIIII. For, 1593. June V.”

The whole square is intended to demonstrate the powers of language to accommodate the queen’s praises in God’s providential order. Further, the arrangement of the words forms a comment on the political situation at the time: St. George is the patron saint of England, St. Andrew is the patron saint of Scotland, and the pillars may represent Elizabeth’s chosen emblem, the Pillars of Hercules. “The fact that the words of the square can be forced to yield meaning within the imposed specifications is amazing in itself.”

(Thomas P. Roche Jr., Petrarch and the English Sonnet Sequences, 1989.)