Search Results for: lee sallows

Inventory Control

In 2015 British computer scientist Chris Patuzzo produced a self-enumerating pangram — a sentence that itemizes its own contents — that records its totals as percentages:

This sentence is dedicated to Lee Sallows and to within one decimal place four point five percent of the letters in this sentence are a’s, zero point one percent are b’s, four point three percent are c’s, zero point nine percent are d’s, twenty point one percent are e’s, one point five percent are f’s, zero point four percent are g’s, one point five percent are h’s, six point eight percent are i’s, zero point one percent are j’s, zero point one percent are k’s, one point one percent are l’s, zero point three percent are m’s, twelve point one percent are n’s, eight point one percent are o’s, seven point three percent are p’s, zero point one percent are q’s, nine point nine percent are r’s, five point six percent are s’s, nine point nine percent are t’s, zero point seven percent are u’s, one point four percent are v’s, zero point seven percent are w’s, zero point five percent are x’s, zero point three percent are y’s and one point six percent are z’s.

The next challenge was to extend the precision beyond one decimal place. Impressively, Matthias Belz produced this specimen in 2017:

Rounded to five decimal places, two point six five two five two percent of the letters of this sentence are a’s, zero point zero eight eight four two percent are b’s, two point six five two five two percent are c’s, zero point four four two zero nine percent are d’s, nineteen point eight zero five four eight percent are e’s, three point four four eight two eight percent are f’s, one point seven six eight three five percent are g’s, two point nine one seven seven seven percent are h’s, seven point eight six nine one four percent are i’s, zero point zero eight eight four two percent are j’s, zero point zero eight eight four two percent are k’s, zero point three five three six seven percent are l’s, zero point one seven six eight three percent are m’s, ten point two five six four one percent are n’s, eight point nine three zero one five percent are o’s, four point seven seven four five four percent are p’s, zero point zero eight eight four two percent are q’s, nine point five four nine zero seven percent are r’s, four point nine five one three seven percent are s’s, nine point six three seven four nine percent are t’s, two point zero three three six zero percent are u’s, two point seven four zero nine four percent are v’s, one point six seven nine nine three percent are w’s, zero point nine seven two five nine percent are x’s, zero point zero eight eight four two percent are y’s and one point nine four five one eight percent are z’s.

These numbers are still rounded, so later that year he surpassed that with an instance giving precisely accurate values:

Exactly three point eight seven five percent of the letters of this autogram are a’s, zero point one two five percent are b’s, three point five percent are c’s, zero point two five percent are d’s, twenty-one point two five percent are e’s, three point seven five percent are f’s, zero point three seven five percent are g’s, one point five percent are h’s, seven point two five percent are i’s, zero point one two five percent are j’s, zero point one two five percent are k’s, zero point three seven five percent are l’s, zero point two five percent are m’s, nine point seven five percent are n’s, seven point five percent are o’s, six point five percent are p’s, zero point one two five percent are q’s, nine point three seven five percent are r’s, five point one two five percent are s’s, ten percent are t’s, zero point three seven five percent are u’s, four point six two five percent are v’s, one point five percent are w’s, zero point five percent are x’s, zero point three seven five percent are y’s and one point five percent are z’s.

Inventory

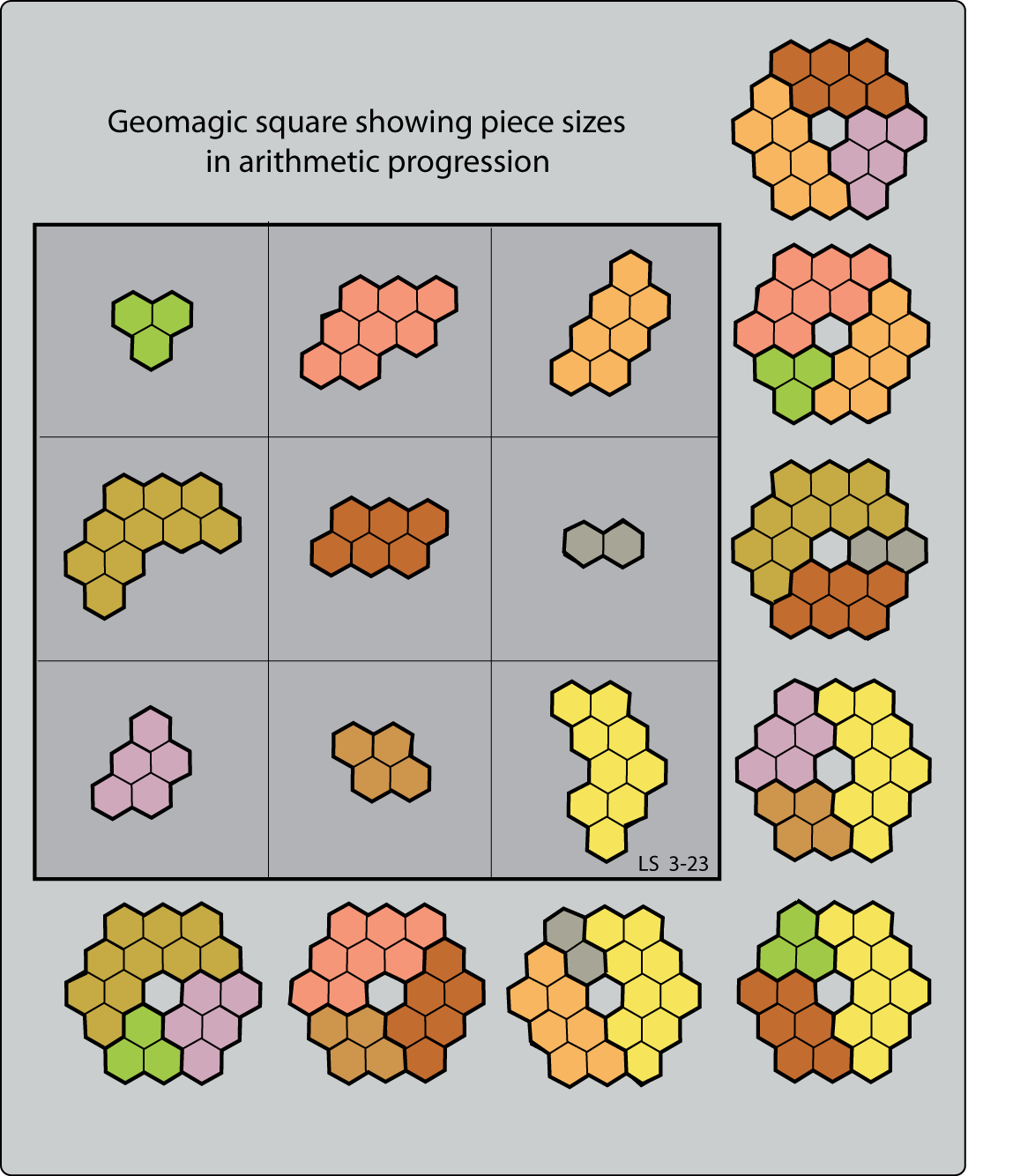

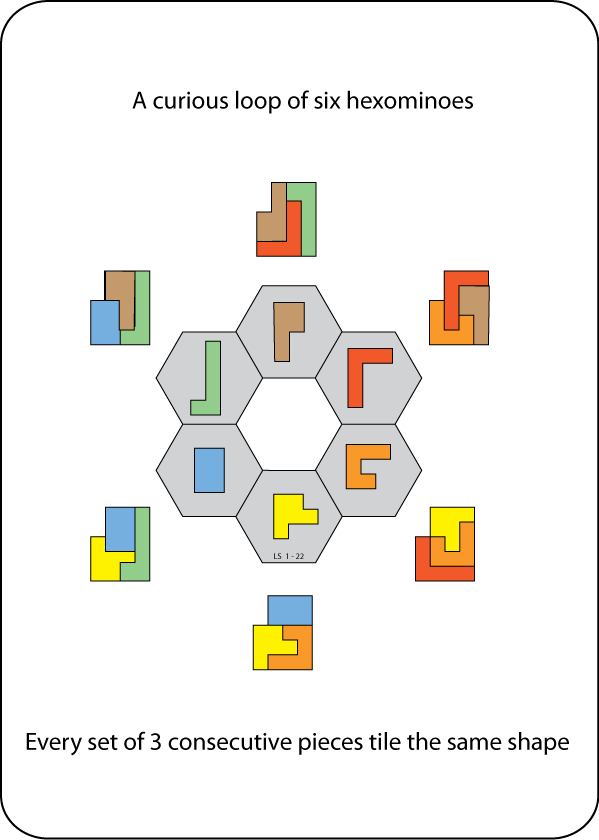

A Polyhex Square

Constitutional Crisis

Fair and Square

From Lee Sallows:

(Thanks, Lee!)

Eight Flights

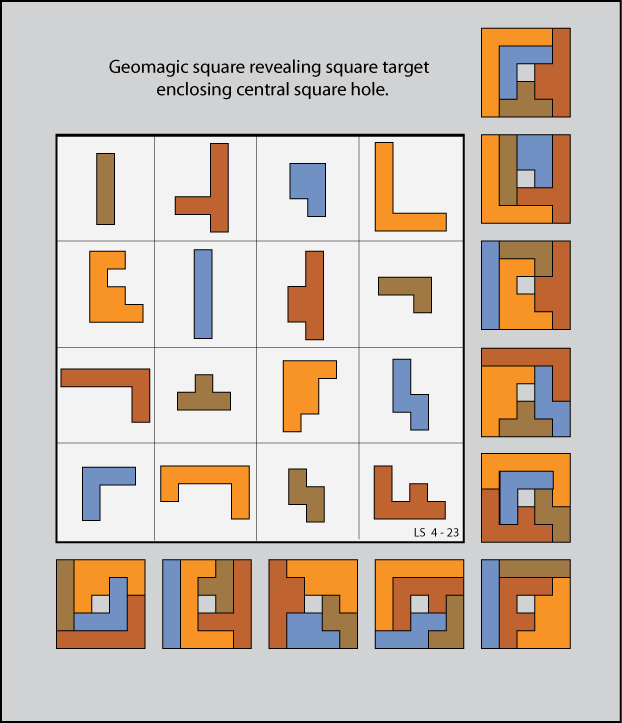

From Lee Sallows, a geomagic square with a staircase theme:

(Thanks, Lee!)

Three by Three

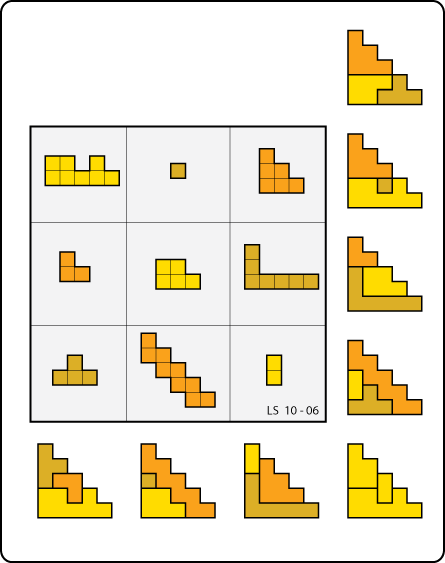

From Lee Sallows:

(Thanks, Lee!)

Chronological Order

By Lee Sallows: If the letters BJFGSDNRMLATPHOCIYVEU are assigned to the integers -10 to 10, then:

J+A+N+U+A+R+Y = -9+0-4+10+0-3+7 = 1 F+E+B+R+U+A+R+Y = -8+9-10-3+10+0-3+7 = 2 M+A+R+C+H = -2+0-3+5+3 = 3 A+P+R+I+L = 0+2-3+6-1 = 4 M+A+Y = -2+0+7 = 5 J+U+N+E = -9+10-4+9 = 6 J+U+L+Y = -9+10-1+7 = 7 A+U+G+U+S+T = 0+10-7+10-6+1 = 8 S+E+P+T+E+M+B+E+R = -6+9+2+1+9-2-10+9-3 = 9 O+C+T+O+B+ER = 4+5+1+4-10+9-3 = 10 N+O+V+E+M+B+E+R = -4+4+8+9-2-10+9-3 = 11 D+E+C+E+M+B+E+R = -5+9+5+9-2-10+9-3 = 12

Similarly, if -7 to 7 are assigned SROEMUNFIDYHTAW, then SUNDAY to SATURDAY take on ordinal values. See Alignment.

(David Morice, “Kickshaws,” Word Ways 24:2 [May 1991], 105-116.)