Plateau’s Laws

Clusters of soap bubbles obey some pleasingly simple rules: They arrange themselves into constant-mean-curvature surfaces (such as pieces of spheres) that meet in threes at 120° along seams, which in turn meet in fours at about 109° angles at points.

“Nothing more complicated ever happens,” writes mathematician Frank Morgan, even in complicated clusters with thousands of bubbles.

Belgian physicist Joseph Plateau observed and recorded this fact in the 19th century, but he offered no proof. More than 100 years would go by before Rutgers University mathematician Jean Taylor produced a complete explanation. Her demonstration required no physics or chemistry, just the principle of area minimization.

Morgan writes, “Many pages of complicated mathematics later came the conclusion: Plateau’s laws, 120° angles, 109° angles, and all.”

(Frank Morgan, “Mathematicians, Including Undergraduates, Look at Soap Bubbles,” American Mathematical Monthly 101:4 [April 1994], 343-351.)

Encore

Ballerina Anna Pavlova was famous for creating The Dying Swan, a four-minute solo ballet depicting the last moments in the life of a swan, after the cello solo “Le Cygne” in Camille Saint-Saëns’ Le Carnaval des animaux. She performed the role some 4,000 times; American critic Carl Van Vechten called it “the most exquisite specimen of [Pavlova’s] art which she has yet given to the public.”

Two days after Pavlova’s death in 1931, the orchestra at London’s Apollo Theater paused between selections and began to play “The Death of the Swan.” Dance writer Philip J.S. Richardson recorded what came next:

The curtain went up and disclosed an empty, darkened stage draped in grey hangings, with the spotlight playing on someone who was not there. The large audience rose to its feet and stood in silence while the tune which will forever be associated with Anna Pavlova was played.

“It was an unforgettable moment,” he wrote.

First Things First

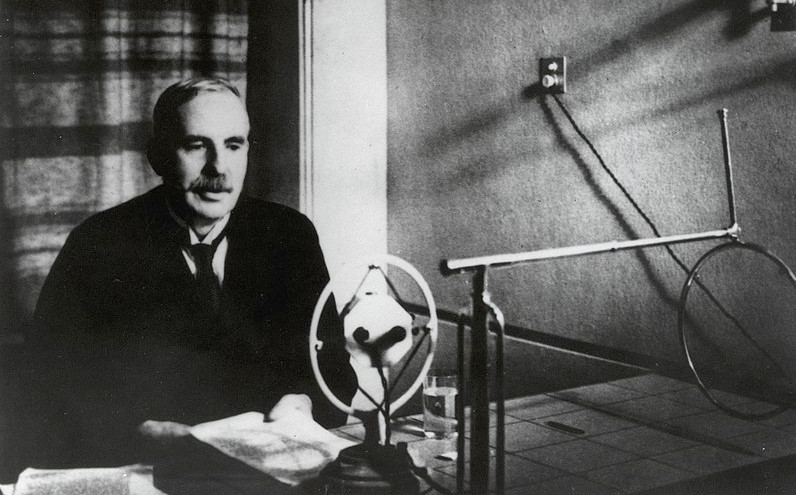

During World War I, Ernest Rutherford worked tirelessly on a secret project to detect submarines by sonar. But on one occasion he did decline to attend a committee meeting.

“I have been engaged in experiments which suggest that the atom can be artificially disintegrated,” he wrote. “If it is true it is of far greater importance than a war.”

The Blind Leading

I just ran across this absurd sentence in Love in the Lead, Peter Brock Putnam’s 1979 history of the seeing eye dog:

As late as the 1950s, an association for the blind in a southern city used to post sighted monitors at the entrance for its Christmas party, so that the blind guests who could not see each other’s color would be able to segregate racially.

Apparently this is true. In 1945 federal judge J. Skelly Wright was attending a Christmas Eve party at the U.S. attorney’s office in New Orleans. Across Camp Street, at the Lighthouse for the Blind, he could see another party going on. “He watched the blind people climb the steps to the second floor,” writes journalist Jack Bass. “There, someone met them. He watched a blind Negro led to a party for blacks at the rear of the building. A white person was led to a separate party.”

“They couldn’t see to segregate themselves,” Wright said later. “That upset me a great deal.” In 1956 he ordered Louisiana schools to desegregate. He said that the incident of the Christmas party had given him “my mature and great sympathy for Negroes.” As he told this story to journalist W.J. Weatherby, he “was so moved that he could not complete the story for several minutes.”

An Overlooked Death

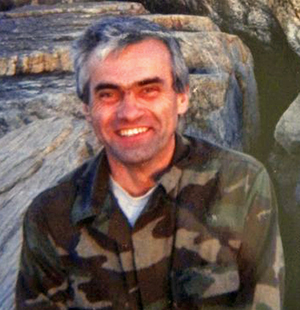

Late one night in 2001, Polish immigrant Henryk Siwiak set out to find a Pathmark supermarket in Brooklyn in order to start a new job. Around 11:40 p.m., residents in the area heard an argument followed by gunshots. Siwiak was found dead face down in Decatur Street, shot in the lung. A trail of blood showed that he had staggered there from Albany Avenue seeking help.

Unfortunately, this happened on September 11, the day of the terrorist attacks. Siwiak spoke poor English and was wearing camouflage clothing, which may have led his assailant to think he was associated with the attacks. In any case, with the city in chaos, police could not attend as closely to the case as they otherwise would have, and that day’s news coverage was devoted to the attacks, which may have prevented residents with potentially useful information from coming forward.

The case remains unsolved. “I’m afraid this is forever,” Henryk’s widow Ewa told the New York Times in 2011. Because the terror victims were not included in the city’s crime statistics, Siwiak’s death is the only homicide recorded in New York City on that day.

Looking the Part

As he was preparing King Kong for his 1933 screen debut, producer Merian C. Cooper was continually dissatisfied with sculptor Marcel Delgado’s sensitive models of the giant ape. “I want Kong to be the fiercest, most brutal, monstrous damned thing that has ever been seen,” he insisted. Animator Willis O’Brien objected that the audience wouldn’t sympathize with a monster that lacked human qualities, but Cooper was adamant: “I’ll have women crying over him before I’m through, and the more brutal he is the more they’ll cry at the end.”

He called the American Museum of Natural History and asked for the exact dimensions of a large male gorilla. On the afternoon of December 22, 1931, he gave O’Brien a telegram from the curator of zoology:

DIMENSIONS LARGE MALE GORILLAS HEIGHT HEEL TO CROWN SIXTY SEVEN INCHES SPAN OUTSTRETCHED ARMS HUNDRED TWO INCHES CHEST OVER NIPPLES SIXTY CIRCUMFERENCE AROUND BELLY SEVENTY TWO STOP PHOTOGRAPH OF ADULT HUMAN AND GORILLA SKELETONS COMPARED SEE HAECKEL E NINETEEN THREE ANTHROPOGENIE VOLUME TWO PAGE SEVEN NINETY EIGHT FOR OTHER DATA YERKES NINETEEN TWENTY NINE THE GREAT APES AND DUCHAILLU EIGHTEEN SIXTY TWO ADVENTURES IN EQUATORIAL AFRICA — HARRY C RAVEN

“Now that’s what I want,” he said. O’Brien quit on the spot and walked out of the studio, but after a few drinks together the two returned to work. Eventually they agreed on a compromise. In The Making of King Kong, Orville Goldner writes, “The scene would be repeated several times during the year to come.”

Armageddon

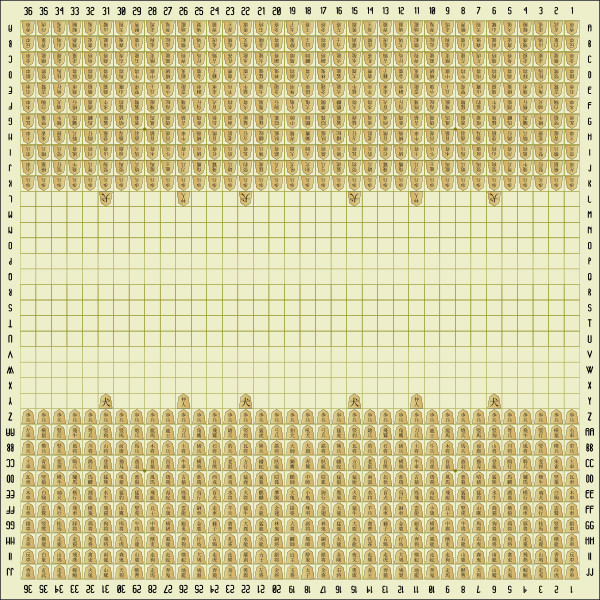

In 1997 researchers rediscovered a 16th-century variant of Japanese chess called taikyoku shōgi, perhaps the largest and most challenging chesslike game ever devised. Played with 804 pieces of 209 types on a board of 1,296 squares, a single game might require a thousand moves played over several long sessions.

“The first difficulty lies in deciphering the minuscule characters identifying a nearly endless crowd of pieces,” write Jean-Louis Cazaux and Rick Knowlton in A World of Chess. “The players must have long arms, tiny fingers, microscopic vision and a huge memory.”

Only two sets of pieces have been restored, and the known rules sets disagree and have yet to be reconciled, but even Wikipedia’s summary of the rules reflects the jaw-dropping complexity of the game.

Sweet Mystery of Life

For 20 years, someone stocked a Coke machine on Seattle’s Capitol Hill with obscure, sometimes discontinued drinks such as Grape Fanta, Mountain Dew White Out, Hawaiian Punch, and raspberry Nestea Brisk. The price was 75 cents, and each button read simply “? MYSTERY ?”

The machine stood in front of Broadway Locksmith on John Street, but the locksmith claimed to know nothing about its operator. When the city passed a tax on sugary drinks in January 2018, the machine raised its price to $1.00. Six months later, it disappeared, leaving only a message on its Facebook page: “Going for a walk, need to find myself. Maybe take a shower even.”

It hasn’t been seen since. Do machines take walks?

The “Dicta Boelcke”

Principles of aerial combat devised by World War I German flying ace Oswald Boelcke, the “father of air fighting tactics”:

- Try to secure advantages before attacking. If possible, keep the sun behind you.

- Always carry through an attack when you have started it.

- Fire only at close range and only when your opponent is properly in your sights.

- Always keep your eyes on your opponent, and never let yourself be deceived by ruses.

- In any form of attack it is essential to assail your opponent from behind.

- If your opponent dives on you, do not try to avoid his onslaught, but fly to meet it.

- When over the enemy’s lines, never forget your own line of retreat.

- For the Staffel [fighter squadrons]: Attack on principle in groups of four or six. When the fight breaks up into a series of single combats, take care that several do not go for one opponent.

“He certainly didn’t love war and he personally disliked killing,” writes Dan Hampton in Lords of the Sky, his history of fighter pilots and air combat. “It was not a sport to him, as it was with others, nor was it a game. It was something he had to do, so he did it well.” When he died in a crash, his British enemies dropped a wreath behind German lines with the message “To the memory of Captain Boelcke, our brave and chivalrous opponent. From the English Royal Flying Corps.” French, Italian, and British pilots sent wreaths and messages from prisoner-of-war camps, and Manfred von Richthofen said of his mentor, “I am only a fighting airman, but Boelcke was a hero.”