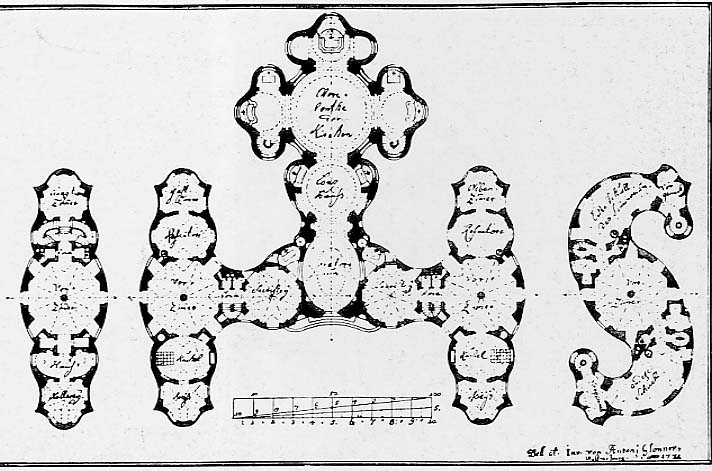

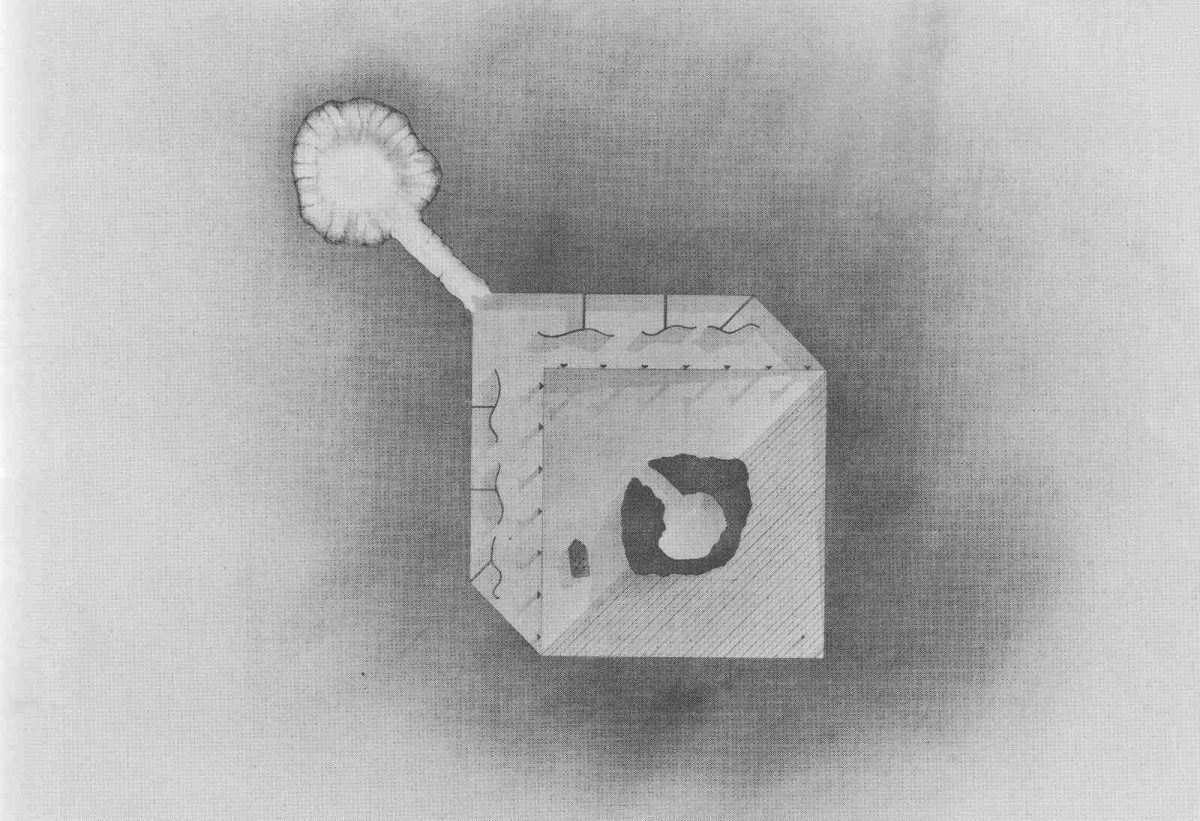

This is just an image that I liked. In 1983, in preparation for an exhibition at New York’s Leo Castelli Gallery, architect B.J. Archer invited some of his friends to submit plans for a folly — “an object which embodies no function, save for demarcation, or is useful only for a small segment of daily life.”

Emilio Ambasz submitted the following. “I never thought about it in words,” he wrote, “It came to me as an image — full-fledged, clear and irreducible, like a vision”:

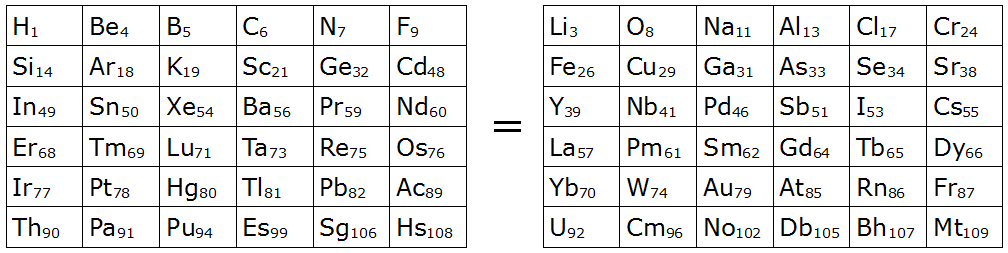

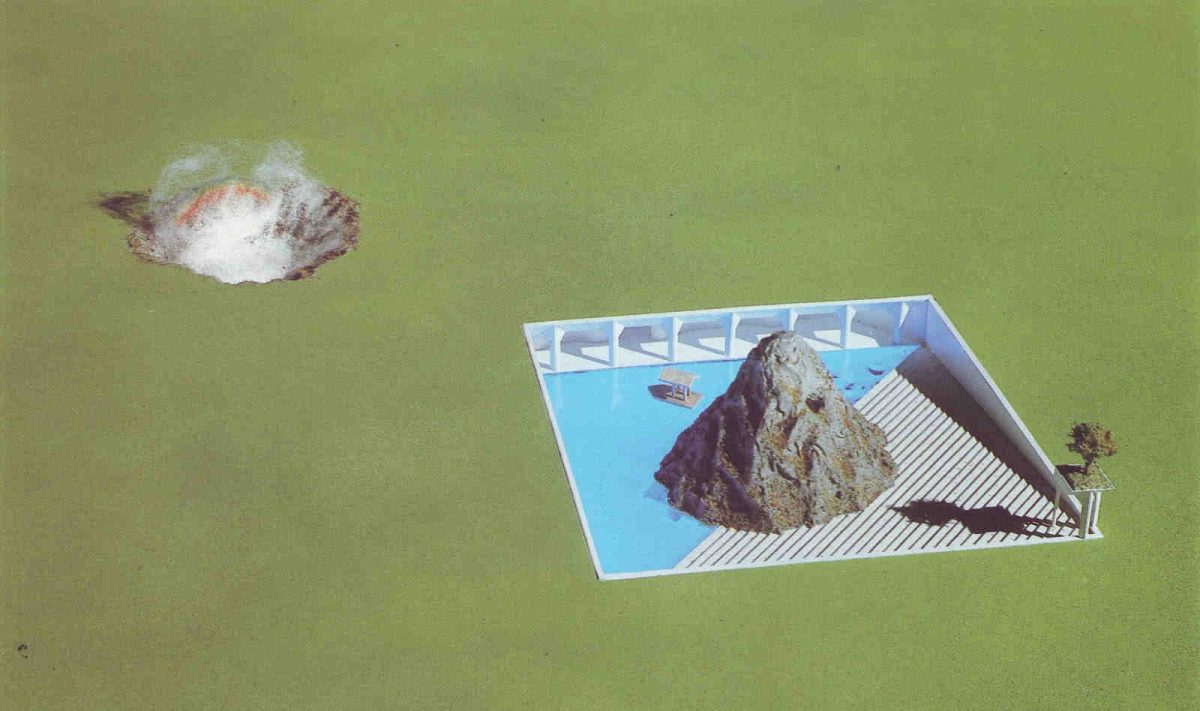

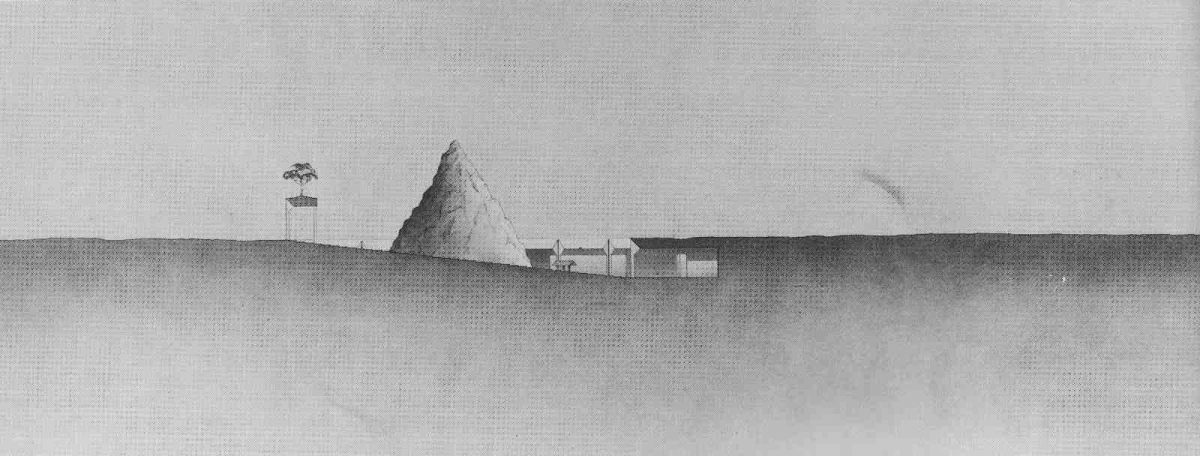

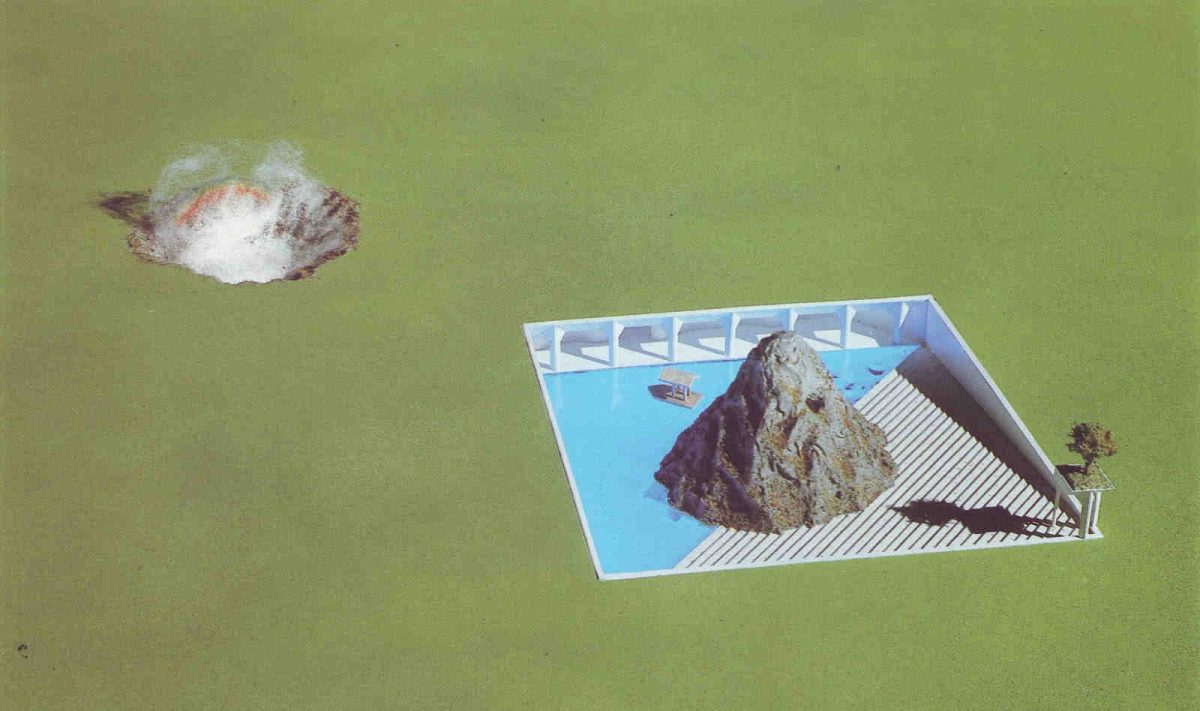

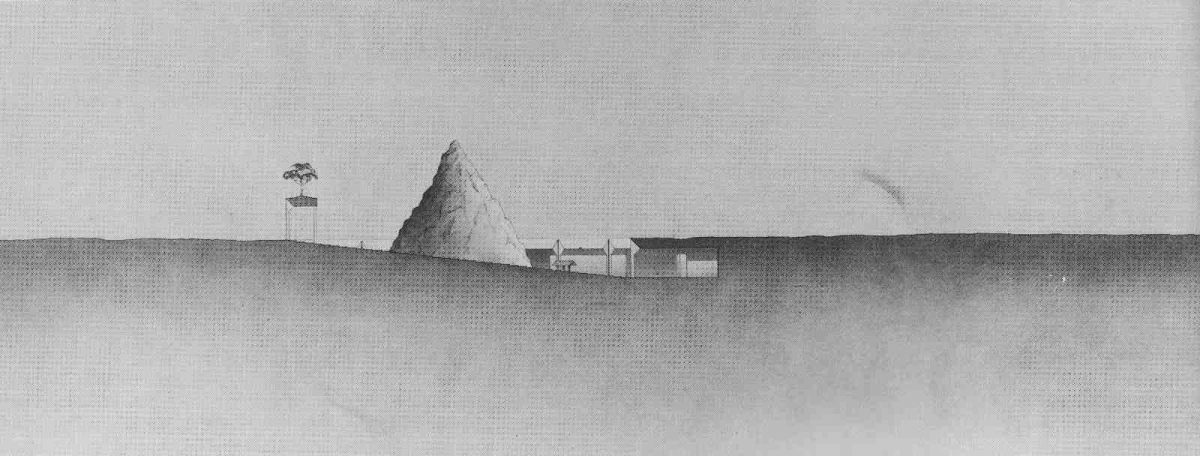

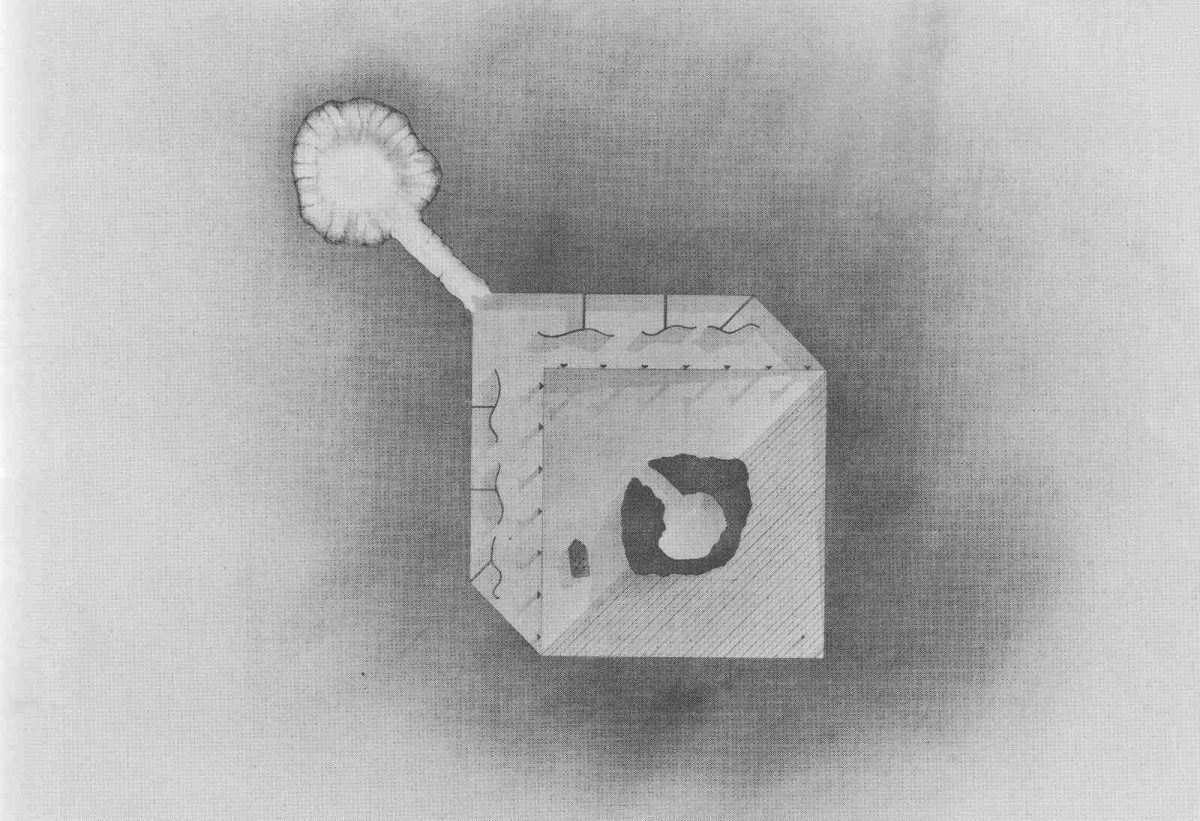

I fancied myself the owner of a wide grazing field, somewhere in the fertile plains of Texas or in the province of Buenos Aires. In the middle of this field was a partly sunken open-air construction. I felt as if this place had always existed. The entrance was marked by a three-column baldachino supporting a lemon tree. From the entrance a triangular earthen plane stepped gently toward the diagonal of a large, square sunken courtyard — half earth, half water. A rocky mass rose in the centre of the courtyard resembling a mountain. A barge made of logs floated on the water; it was sheltered by a thatched roof supported by wooded trusses resting on four square, sectioned, wood pillars. Using a long pole, the barge could be sculled into an opening in the mountain. Once inside this cave I could alight the barge on a cove-like shore illuminated by the zenithal opening. More often, I used the barge to reach an L-shaped cloister where, shaded from the sun or sheltered from the wind, I could sit and read, draw or just think. The cloister was defined on the outside by the water basin and on the inside by a number of undulating planes screening alcove-like spaces.

In the alcoves he stored childhood toys, school notebooks, a stamp collection, and an old military uniform. “Not all things stored in these alcoves were there because they had given me pleasure; they were things I could not discard.” In his imagination he would traverse the water basin occasionally to dress up in the uniform, “assuring myself I had not put on too much weight.”

One last thing: In place of one of the alcoves was the entrance to a tunnel leading to an open pit full of fresh mist. “I never understood how this cold water mist originated, but it never failed to produce a rainbow.”

(From Archer’s Follies, 1983.)