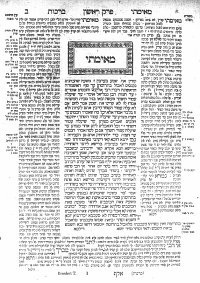

Writing in Psychological Review in 1917, Berkeley psychologist George Stratton reported the startling achievements of Jewish scholars known as Shass Pollaks, who would memorize the entire Babylonian Talmud — not just the text, but the position of every word on every page:

“A pin would be placed on a word, let us say, the fourth word in line eight; the memory sharp would then be asked what word is in the same spot on page thirty-eight or fifty or any other page; the pin would be pressed through the volume until it reached page thirty eight or page fifty or any other page designated; the memory sharp would then mention the word and it was found invariably correct. He had visualized in his brain the whole Talmud; in other words, the pages of the Talmud were photographed on his brain. It was one of the most stupendous feats of memory I have ever witnessed and there was no fake about it.”

Stratton also quotes Judge Mayer Sulzberger of Philadelphia, who had seen a Shass Pollak put down a pencil at random in the Talmud and immediately name the word on which it had lighted.

These achievements, Stratton wrote, “should be stored among the data long and still richly gathering for the study of extraordinary feats of memory.”