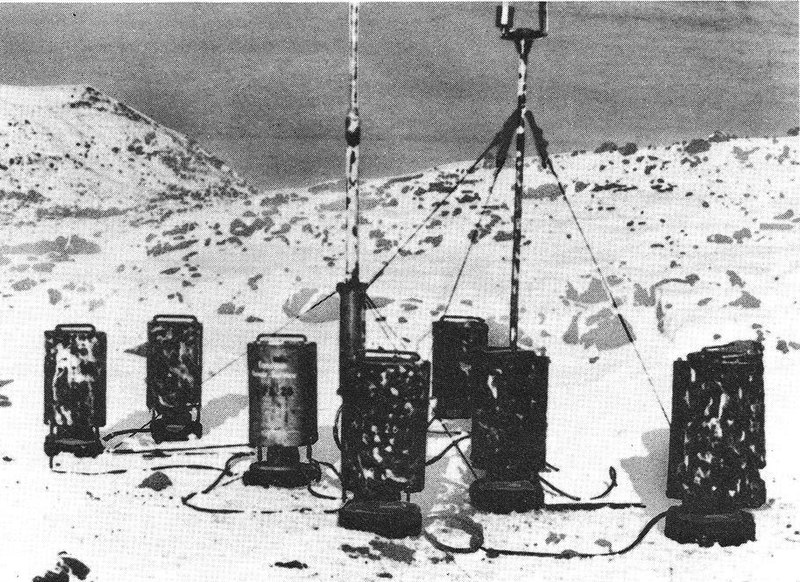

During World War I, British physicist G.I. Taylor was asked to design a dart to be dropped onto enemy troops from the air. He and a colleague dropped a bundle of darts as a trial and then “went over the field and pushed a square of paper over every dart we could find sticking out of the ground.”

When we had gone over the field in this way and were looking at the distribution, a cavalry officer came up and asked us what we were doing. When we explained that the darts had been dropped from an airplane, he looked at them and, seeing a dart piercing every sheet remarked: ‘If I had not seen it with my own eyes I would never have believed it possible to make such good shooting from the air.’

(The darts were never used — “we were told they were regarded as inhuman weapons and could not be used by gentlemen.”)

(From T.W. Körner, The Pleasures of Counting, 1996.)