From the log of the S.S. Esso Lancashire, sailing off Durban in the Indian Ocean, Aug. 5, 1968:

At 0845 GMT the vessel entered a wave at an altitude of approx. 20 ft and emerged seconds later very much the worse for wear. If Cdre. W.S. Byles, R.D. has any idea where ‘The One from Nowhere’ went, we found the wave that should be with his trough! The wave passed unbroken over the monkey island (a height of about 60 ft) and we struck it well above the trough. It was preceded by a wave slightly larger than usual and we rode that one fairly comfortably but the wavelengths to the big one appeared much less and we just did not make it.

The log for 0745 had noted swell reaching heights of 20 feet. If the monkey island was 60 feet tall then this wave towered 80 feet above the trough, four times the average wave height.

The “one from nowhere” was a deep trough encountered by RMS Edinburgh Castle in 1964: Commodore W.S. Byles reported that the cruiser had “charged, as it were, into a hole in the ocean at an angle of 30° or more, shoveling the next wave on board at a height of 15 to 20ft before she could recover.”

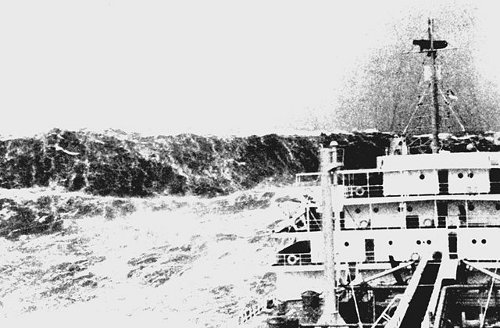

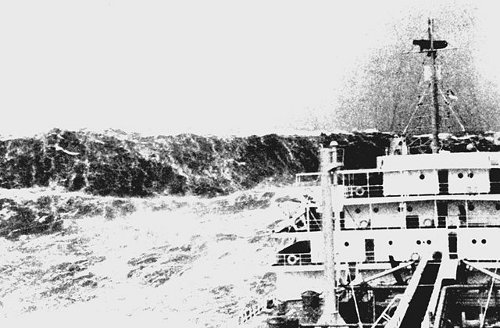

The photo above was taken in the Bay of Biscay around 1940 — a merchant ship was laboring in heavy seas off the coast of France when a crew member photographed a huge wave behind them.

On May 5, 1916, Ernest Shackleton and three exhausted companions were sailing in a small boat across the South Atlantic, trying to reach a settlement and get help for their shipmates, who were stranded on Elephant Island. At midnight Shackleton, alone at the tiller, looked behind them and noticed a horizontal line in the sky. At first he thought this was a rift in the clouds, but gradually he realized it was the white crest of an enormous wave:

I shouted ‘For God’s sake, hold on! it’s got us.’ Then came a moment of suspense that seemed drawn out into hours. White surged the foam of the breaking sea around us. We felt our boat lifted and flung forward like a cork in breaking surf. We were in a seething chaos of tortured water; but somehow the boat lived through it, half full of water, sagging to the dead weight and shuddering under the blow. We bailed with the energy of men fighting for life, flinging the water over the sides with every receptacle that came to our hands, and after ten minutes of uncertainty we felt the boat renew her life beneath us.

“During twenty-six years’ experience of the ocean in all its moods I had not encountered a wave so gigantic,” Shackleton wrote later. “It was a mighty upheaval of the ocean, a thing quite apart from the big white-capped seas that had been our tireless enemies for many days.” But they survived the disaster and reached their goal.