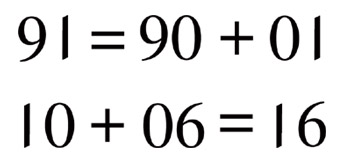

A doubly true equation by Basile Morin.

A doubly true equation by Basile Morin.

OHIO reads the same sideways.

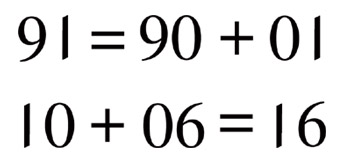

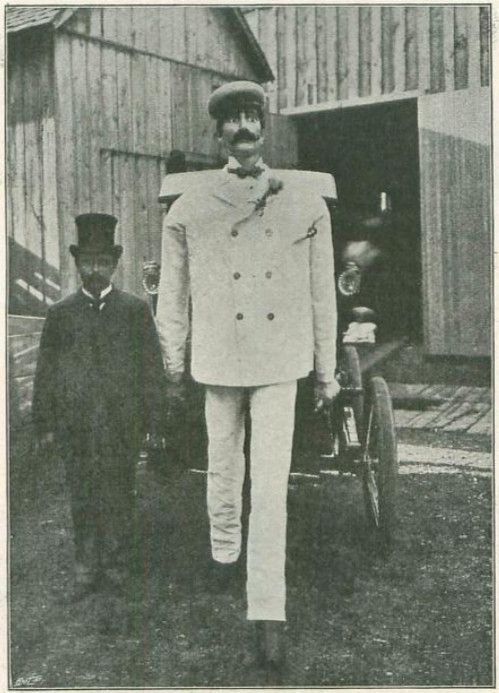

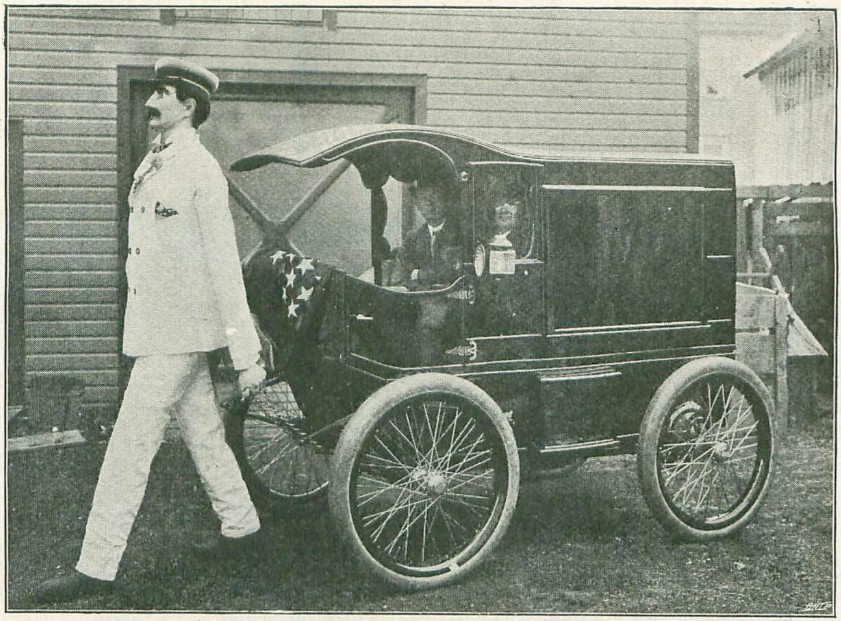

In 1900, Louis Philip Perew of Tonawanda, New York, built a “gigantic man” of wood, rubber, and metal that “walks, talks, runs, jumps, [and] rolls its eyes.”

Standing 7 foot 5 in size 13 1/2 shoes and clothed in white duck, the nameless man “walked smoothly, and almost noiselessly” at an exhibition for the Strand, circling the hall twice without stopping. Perew was cagey as to its inner workings, saying only that its aluminum skin concealed a steel framework.

When a large block of wood was placed in its path, “it stopped, rolled its eyes in the direction of the obstacle, as if calculating how it could surmount it. It then deliberately raised the right foot, placed it upon the object, and stepped down on the other side. The motion seemed uncannily realistic. You almost feel like shrinking from before those rolling eyes. The visionless orbs are operated by means of clock-work situated within the head.”

When the robot announced, “I am going to walk from New York to San Francisco,” Perew acknowledged that the team planned to send it across the continent drawing a light wagon bearing two men. He claimed it could cover 20 miles in an hour.

I don’t know any more about it. This isn’t the first mechanical man we’ve encountered — a steam-powered robot had been proposed as early as 1868. But neither seems to have gone anywhere.

03/23/2025 UPDATE: Readers Kendra Colman, Justin Hilyard, and Hans Havermann point out that Cybernetic Zoo has a whole summary on the “Electric Man” and its history, including Perew’s original 1894 patent and various news articles (with additional photos) from 1895 up to 1914. Apparently the effect is deceiving — the man doesn’t actually pull the wagon, the wagon pushes the man. Many thanks to everyone who’s written in about this.

We have a strong intuition that it’s wrong to punish someone for a crime he hasn’t committed, but is this always the case? Algy, an Alaskan motorist, and Ben, a traffic policeman, both know reliably that Algy intends to speed on a remote, unpatrolled, but radar-surveyed highway at 10:31 tomorrow morning. They also know that, if this happens, police won’t be able to reach the scene of the offense until several hours after it’s been committed.

Algy radios Ben with an offer: If Ben issues a ticket for this crime before it occurs, Algy will pay the fine. If Ben doesn’t issue the ticket until after the offense has occurred, then Algy will flee the country to avoid paying the fine. Ben thinks about this, then issues the ticket now, writing in tomorrow’s date. He delivers the ticket to Algy’s address, where Algy’s wife gives him Algy’s check for the fine, which Ben cashes immediately. At 10:31 tomorrow, Algy exceeds the speed limit as described.

University of Hong Kong philosopher Christopher New writes, “If this example is valid, it suggests that there may be room in our moral thought for the notion of prepunishment [punishment before an offense is committed], and that it may be only epistemic, rather than moral, constraints that prevent us from practising it.”

(Christopher New, “Time and Punishment,” Analysis 52:1 [January 1992], 35-40.)

This 1904 comic by Gustave Verbeek (click to enlarge) is a sort of visual palindrome — the first six panels are presented conventionally, and then they’re displayed again in reverse order and upside down to compose the story’s second half. Even the written messages change their meaning: why big buns am mad u! becomes in pew we sung big hym, and so on. Only the captions beneath the first panels are discarded in the second half.

vatic

adj. relating to a prophet

futurition

n. future existence

natalitial

adj. of or relating to a person’s birth

aporetic

adj. inclined to raise objections

In 2000, three sisters from Inverness bought a £1 million insurance policy to cover the cost of bringing up the infant Jesus Christ if one of them had a virgin birth.

Simon Burgess, managing director of britishinsurance.com, told the BBC, “The people were concerned about having sufficient funds if they immaculately conceived. It was for caring and bringing up the Christ. We sometimes get weird requests and this is the weirdest we have had.”

The company withdrew the policy in 2006 after objections by the Catholic Church. “The burden of proof that it was Christ had rested with the women and any premium on the insurance was donated to charity, said Mr Burgess.”

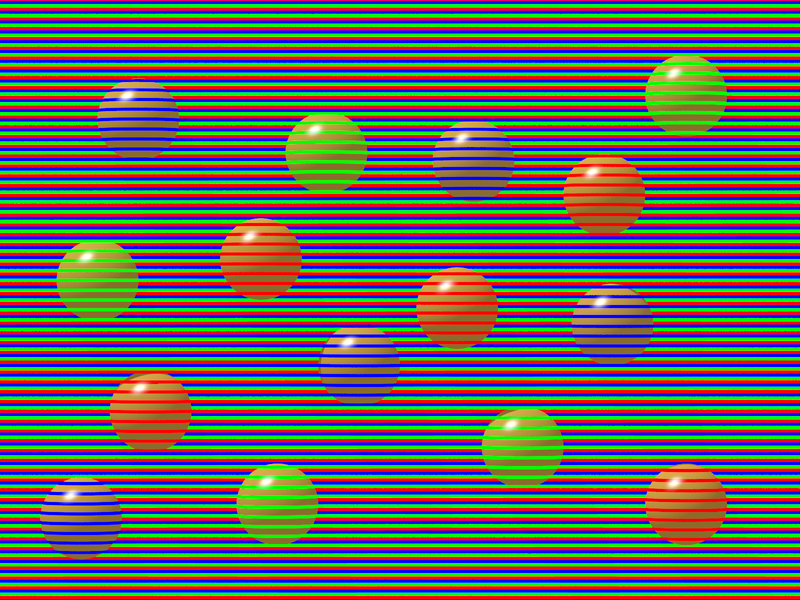

An illusion by University of Texas engineer David Novick: All the spheres have the same light-brown base color (RGB 255,188,144). The intervening foreground stripes seem to impart different hues. See this Twitter thread for the same image with the foreground stripes removed.

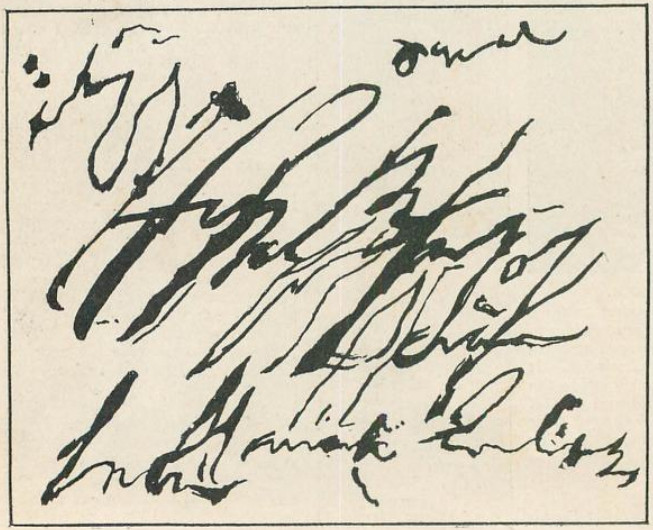

From the Strand, May 1899:

Our next photograph is a facsimile of an address on a letter that found its way from Spain to the G.P.O., St. Martin’s-le-Grand. Remarkable as it may seem, this specimen of handwriting was deciphered by ‘the blind man of St. Martin’s,’ and the letter safely reached its destination. It is addressed to the ‘Spanish Ambassador (or Embassy), London.’

(The “blind men” were “the decipherers of illegible and imperfect addresses” in the returned letter office of the General Post Office. Further examples.)

In Bologna, the former convent of San Michele in Bosco contains a 162-meter hallway that’s “aimed” at the Asinelli tower 1,407 meters from the window. This produces an odd effect: As you move north along the hallway toward the window, you’re approaching the tower, yet it seems to shrink. This is because the retinal size of the window’s aperture increases enormously as you approach it, while the retinal size of the distant tower remains relatively unchanged.

Similarly, as you back away from the window the tower seems to grow and draw closer, because the “shrinking” window shuts out the panorama, leaving only the tower in view. The illusion was first reported on a 1714 map by Paolo Battista Baldi of the University of Bologna.

The city contains a second “vista paradox” in the hermitage of Ronzano, where another long hallway is oriented toward the Sanctuary of San Luca 1,970 meters away. The Sanctuary seems to shrink as one approaches the frame and to grow as one retreats.