Portuguese graffiti artist Odeith invested 30 spray cans and 10 hours to transform two concrete walls into a wrecked bus.

Oddities

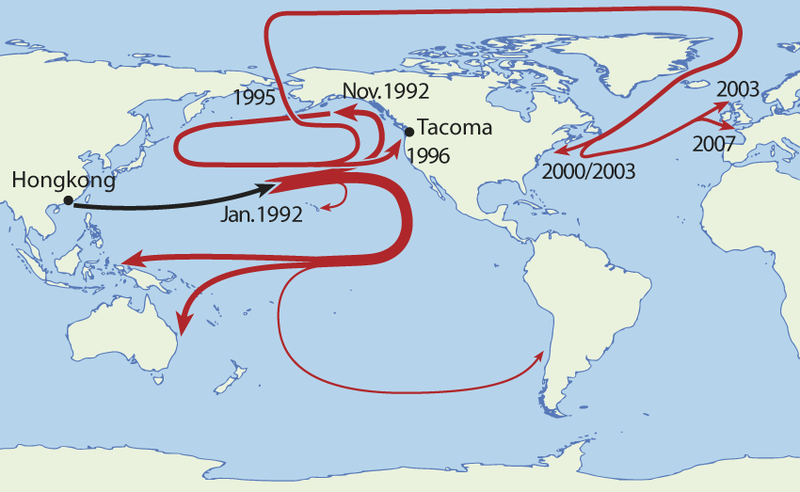

The Friendly Floatees

During a storm in January 1992, a container was swept overboard from a ship in the North Pacific. As it happened, it contained 28,800 children’s bath toys, and oceanographer Curtis Ebbesmeyer realized they offered the basis for a serendipitous study of surface currents. Working with his colleague James Ingraham, Ebbesmeyer began to track the toys as they drifted around the globe, accumulating reports from beachcombers, coastal workers, and local residents as they began to wash up on beaches. Using computer models, they were able to predict correctly that toys would make landfall in Washington state, Japan, and Alaska, and even become trapped in pack ice and spend years creeping across the top of the world before making an eventual reappearance in the North Atlantic. “Ultimately,” Ebbesmeyer wrote, “the toys will turn to dust, joining the scum of plastic powder which rides the global ocean.”

For some reason, media accounts of the story always carried the image of a solitary rubber duck, though the toys had also included beavers, turtles, and frogs. “Maybe it’s a kind of racism,” Ebbesmeyer speculated to journalist Donovan Hohn in 2007. “Speciesism.”

See Ambassador.

A Double Disaster

The high-altitude glacial lake Roopkund, in the Indian state of Uttarakhand, contains a large number of human skeletons. Local legend tells of a royal party who were killed by a large hailstorm near here, and many of the skeletons show signs of blows by large round objects falling from above. Radiocarbon dating estimates that these people died around 850 CE.

But another set of victims seem to have succumbed much more recently, a group from the eastern Mediterranean who died only 200 years ago. So the casualties can’t all be attributed to a single catastrophic event, but the full truth is still emerging.

One of a Kind

The Yemeni island Socotra, off the tip of the Horn of Africa in the Arabian Sea, is so isolated that nearly 700 of its species are found nowhere else on Earth. The island’s bitter aloe has valuable pharmaceutical and medicinal properties, and the red sap of Dracaena cinnabari, above, was once thought to be the blood of dragons.

And this is only what remains after two millennia of human settlement; the island once featured wetlands and pastures that were home to crocodiles and water buffaloes. Tanzanian zoologist Jonathan Kingdon says, “The animals and plants that remain represent a degraded fraction of what once existed.”

Boundaries

A drop of ink has fallen upon the paper and I have walled it round. Now every point of the area within the walls is either black or white; and no point is both black and white. That is plain. The black is, however, all in one spot or blot; it is within bounds. There is a line of demarcation between the black and the white. Now I ask about the points of this line, are they black or white? Why one more than the other? Are they (A) both black and white or (B) neither black nor white? Why A more than B, or B more than A? It is certainly true,

First, that every point of the area is either black or white,

Second, that no point is both black and white,

Third, that the points of the boundary are no more white than black, and no more black than white.

The logical conclusion from these three propositions is that the points of the boundary do not exist.

— Charles Sanders Peirce, “The Logic of Quantity,” 1893

In a Word

jouisance

n. use or enjoyment

Barmecidal

adj. giving only the illusion of plenty

cacœconomy

n. bad management

furibund

adj. irate

The residents of the parking-challenged Hampshire town of Farnborough were delighted in 2016 to learn that a fully equipped car park had been lying unused for five years. The bad news: It could be reached only on foot. It resides on a roof above a gym complex.

Under the plan, motorists would reach the facility via a bridge from an adjoining property. But that site was still under development.

“We have a massive problem with car parking in Farnborough,” councillor Gareth Lyon told the Independent. “To have had this huge car park lying empty defies belief. It is ridiculous.”

(Thanks, Charlie.)

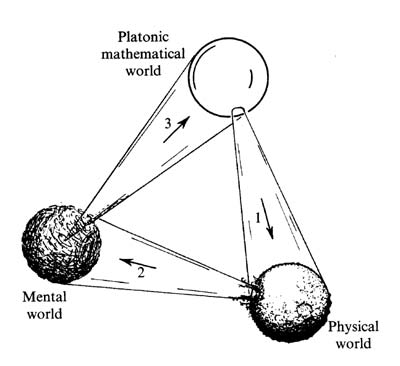

An Eternal Triangle

Similarly, in a waking dream, the greater world is somehow represented in the mind. Part of the wonder here is the wonder of consciousness itself, which William James expressed so clearly when he asked, ‘How can the [world] I am in be simultaneously out there and, as it were, inside my head, my experience?’ Many people think there is still no good answer to this question that I know of — although I recently heard the mathematical physicist Roger Penrose identify a striking corollary of it. It is as if, he said, there are three distinct worlds, equally real, and yet each somehow encompassing the others. There is, first, the world of mathematics — unbounded and infinite, and something that Penrose, following Plato, believes really exists. Then, within the world of mathematics there is the relatively small set of equations that, Penrose says, can explain all of physical reality. And finally, within and made possible by that physical reality there is the world of conscious beings and what they can experience. And yet somehow these conscious beings (or at least the ones who are good enough mathematicians) are capable of comprehending the mathematical world. Each world is therefore somehow nested in turn within another in an eternal loop, like the triangle devised by Penrose that has been called ‘impossibility in its purest form.’

— Caspar Henderson, A New Map of Wonders, 2017

Wait For It

Artist Joe Everson puzzles the crowd before a Milwaukee Bucks game, December 20, 2016.

Will I Am

In the year 1611, when the King James Version of the Bible was published, William Shakespeare was 46 and 47 years old. The 46th word from the start of the 46th Psalm is shake, and the 47th word from the end is spear. Also, the 14th word is will, and the 32nd word from the end is am, preceded by I. And 14 + 32 = 46.

Remarkably, these coincidences obtain also in Richard Taverner’s 1539 Bible, which uses a different wording.

(J. Karl Franson, “A Myth About the Bard,” Word Ways 27:3 [August 1994], 154.)

Truth in Advertising

This giant cask, in Rhineland-Palatinate, has a volume of about 1.7 million liters, making it the largest in the world, large enough in fact to house a wine bar with space for 430 guests. It was built in 1934 by Bad Dürkheim cooper Fritz Keller, who fashioned each stave from a 40-meter spruce tree.

Magnificently, it is called the Giant Cask (Riesenfass). It surpasses the Heidelberg Tun, which had held the record previously.