Nineteenth-century personal ads from the New York Herald:

WILL THE YOUNG LADY WHO ACCIDENTALLY fell while dancing at Barnum’s Museum, on Monday evening, address a note to Interested, Herald office, as a gentleman would like to make her acquaintance, if perfectly agreeable to her? (Jan. 22, 1862)

NIBLO’S, MONDAY EVENING — OCCUPIED adjoining seats in parquet; repeated pressure of arm and foot and hands met when separating. If agreeable, address Bruno, box 211 Herald office. (July 17, 1867)

“WON’T YOU LOOK IN THE HERALD TO-MORROW?” — Will the young lady to whom the above was addressed appoint an interview with the gentleman wearing eyeglasses? Address A.B., Station D. (Dec. 17, 1867)

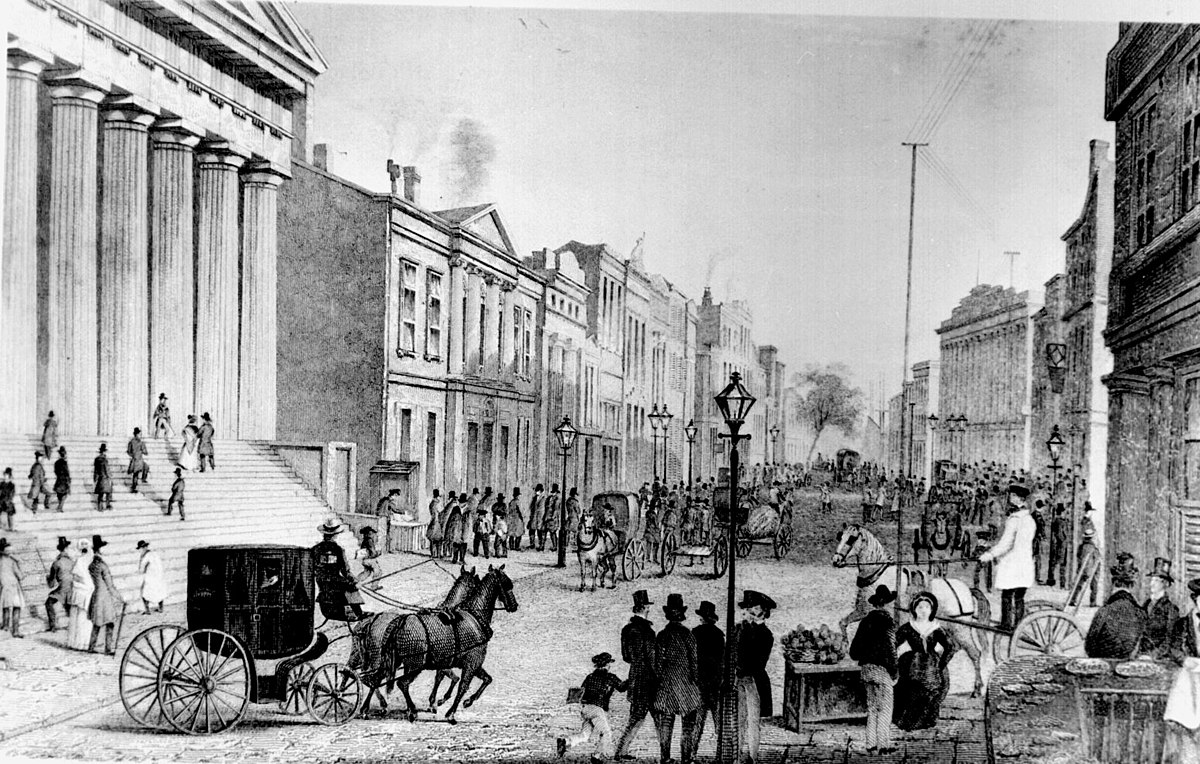

WILL THE YOUNG LADY, WITH CURLS, WEARING a straw bonnet, and I think plaid shawl, and who carried a Herald in her hand, and who came down Park row to Broadway, and down Broadway to Dey street, turning into Dey street about 11 o’clock yesterday, and who in Dey street met and spoke to a gentleman and then went into a fur store in Dey street, near Greenwich, oblige the gentleman who stood on the opposite side of Dey street, as he very much desires an acquaintance? Address T., Herald office. (Feb. 18, 1862)

AN INTRODUCTION IS EARNESTLY SOLICITED OF the young lady or her friends or family, by the gentleman and his mother who stopped their carriage Friday morning to assist a young lady who had jumped from a stage she had just entered, corner 5th av. and 39th st., to rescue the old gentleman who had fallen in the roadway. The young lady is about 20 years of age and very beautiful; wears her hair in large brown waves; has rosy complexion and soft blue eyes; wore Persian gilt walking coat and muff. We desire her acquaintance and to present her in our family. Address MOTHER AND SON, Herald Uptown office. (Feb. 8, 1880)

(From Sara Bader, Strange Red Cow: And Other Curious Classified Ads From the Past, 2005.)